The Russian Orthodox Church has glorified those who suffered under the communist yoke, the Holy New Martyrs and Confessor of Russia. Their feast day is designated on the Sunday nearest to January 25 (Julian calendar). Igumen Damascene (Orlovsky) is a member of the Synodal commission for the canonization of saints of the Russian Orthodox Church, and chairman of the Foundation for the "Remembrance of the Martyrs and Confessors of the Russian Orthodox Church." He is the author of a series of volumes entitled, Martyrs, Confessors, and Ascetics of Piety of the Russian Orthodox Church in the 20th Century."[1]

* * *

Igumen Damascene (Orlovsky).

Igumen Damascene (Orlovsky).

—The Church, in the words of the holy hierarch, is built on the blood of the martyrs, and that is true not only in a connotative sense, but also literally. The Divine Liturgy is served on antimens, into which, according to an ancient tradition, the relics of martyrs are sewn. The Russian Orthodox Church has always borrowed antimens from other Local Orthodox Churches, despite that fact that it is larger in territory and number of members than all the other Local Churches taken together, although it is relatively young and is not commemorated among the first of the patriarchates. But after the canonization of the New Martyrs in the year 2000, we now have enough relics of martyrs to provide antimens to serve the Liturgy on all the Holy Tables until the Second Coming of Christ.

A large thing is seen at a distance, and this is something that is not entirely recognized by our contemporaries, but in the twentieth century, more saints have shown forth in Russia than during the previous 900 years of the Russian Church's existence. There are even more saints who have not been canonized by name.

In the words of St. Simeon the New Theologian, whoever does not want to unite in love and humility of mind with the latest of the saints will never unite with the earlier saints. For, if a person does not recognize or accept the sanctity of those who are so close to him, how can he attain to the sanctity that is so far removed from him?

The experience of the New Martyrs and Confessor is much closer to our times than the experience of the ancient saints. The life conditions and podvig of St. Sergius of Radonezh, for example, or even of saints closer to our times, like St. Seraphim of Sarov, so greatly differ from our modern life that it is practically impossible for us to approach their experience. The saints canonized [by the Moscow Patriarchate] in 2000 lived in our own historical period, and we can enter into their experience. There are very many different saints amongst them—all facets of the multi-faceted Russian individual are reflected in them, and each of us can find someone who is close to us.

—In your opinion, how can we explain the fall of the Russian Empire and Orthodox Monarchy, or the rise of an anti-theistic government, under which terribly cruel persecutions began from the very onset?

Solovki concentration camp. The fishing net workshop. Archpastors and pastors of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Solovki concentration camp. The fishing net workshop. Archpastors and pastors of the Russian Orthodox Church.

As for the spiritual state of Russia before the revolution and of Russian people who lived then—it could hardly be called problem-free. The system of state rule had reached a dead end, which could only have ended in revolution. The "Orthodox Monarchy" was built according to the Western European model. As a result, it viewed serfdom, which was introduced by non-Christian institutions, as something normal, and it could not have gone on any longer. The moral and spiritual state of the Russian people, including in part the peasantry, was also not as healthy as many of our contemporaries would like to believe. Orthodox believers were already a minority among the nineteenth century ruling aristocracy. As for the peasantry—beginning from the late nineteenth century, thanks to the reforms in the sphere of popular education, a massive stripping of religious education occurred with the people. Popular education became almost exclusively the prerogative of the Ministry of Education, and fell into the hands of non-religious bureaucrats, who instilled in the people a way of thinking that was not Orthodox at all. Furthermore, the Orthodox Church was decisively barred from educating and enlightening the people, and the influence of church parish schools had been reduced to zero by the beginning of the twentieth century. Thus, by the beginning of the twentieth century there were already two generations of children who had been educated in such schools, and who turned out to be quite ready to participate in an atheistic, anti-religious revolution.

—You have researched the history of the lives of many new martyrs and confessors. Tell us, how does a person become a saint? Especially since their example is close to our historical reality.

—Every Orthodox person tries to live piously and fulfill the commandments of Christ, for there is nothing more reliable in this brief life than life with the Lord, and man should learn in time to live the life of the Church, life in Christ. If a pious person finds himself in a time of persecution, he can become worthy of a martyr's crown. If a person was spiritually lazy and did not ascetically labor much, then before his martyric end he is given the opportunity to pull himself together spiritually, and show his faithfulness to Christ if only during the final days of his life.

—What is particular to the podvig of martyrdom and confession of Christ under twentieth century conditions?

—It must be said that, unlike the early Christian period, when the podvig of martyrdom was something public, martyrdom in the twentieth century became something unknown to the public at large. Even in the year 2000, the canonization of so many saints was a revelation for many people. That is to say, that this was an even greater feat; for after all, under such conditions a person has more excuses to apostatize—no one would know about it. But there turned out to be very few apostates in the Russian Orthodox Church, and that is why so many saints have shown forth.

—What significance do these thousands of new Russian saints have for the contemporary Orthodox Christian? Will we sufficiently recognize this significance?

—The first significant point is that our martyrs of the latter times, just as those of ancient times, witnessed to the truth. The second is that the martyrs and confessors of the Russian Orthodox Church are prayerful intercessors for us. The third is that the martyrs, their lives, and their podvig of confession are examples for us; they call us to emulate their podvig and prove to us that this is possible. Martyrs, and saints in general, are also beacons that help us not to get lost in the stormy waves of the sea of life. By orienting ourselves on them, we can see what is important and what is unimportant; we can see how the martyrs looked from the viewpoint of their faith and piety at the problems facing man in the modern world.

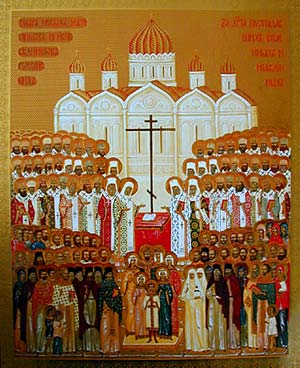

Icon of the New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia.

Icon of the New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia.

Nevertheless, we are now poorly aware of the significance of the martyrs, and therefore we do not manifest the Christian virtue of gratefulness. We are blind in the sense that we do not see the danger to our existence in the present time. If we would see this danger, we would run to the martyrs in prayer as to our close contemporaries and family; we would strive to make use of their experience, to enrich ourselves through it. They, like us, lived in an era of triumphant godlessness—only now, the Lord has through their prayers granted people a little respite.