Source: Pemptousia

November 21, 2016

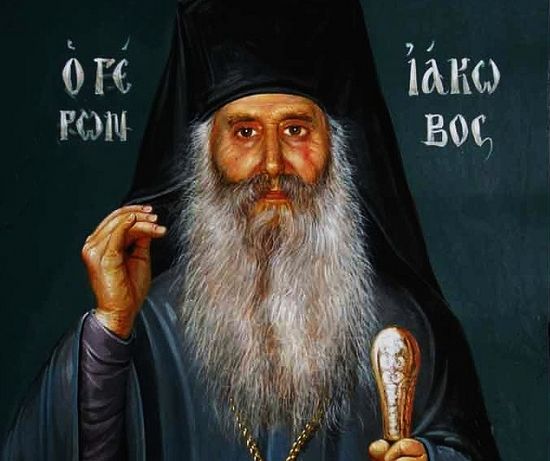

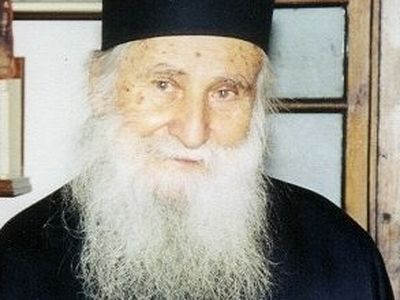

Elder Iakovos Tsalikis (5/11/1920-21/11/1991)

Our age and today’s culture has, unfortunately moved away from the vision and pursuit of sanctity. The Orthodox faith is based on the presence of the saints. Without these, our Church is on the path towards secularization. Naturally, as we know from Scripture, God alone is holy, and sanctity derives from our relationship with Him, and therefore sanctity is theocentric rather than anthropocentric. Our sanctity depends on the glory and the grace of God and our union with Him, not on our virtues. Sanctification assumes the free will of the person being sanctified. As Saint Maximos the Confessor says, all that we bring is our intentions. Without those, God doesn’t act. And Saint John the Damascan repeats that we render honour to the saints ‘for having become freely unified with God and having Him dwell in them and by this participation having become by grace what He is by nature’. The saints didn’t seek to be glorified, but to glorify God, because sanctity means participation in and communion with the sanctity of God.

The source of sanctity in the Orthodox Church is the Divine Eucharist. By partaking of the Holy One, Jesus Christ, we become holy. The ‘holy things’, the Body and Blood of Christ, are given as communion ‘to the holy’, the members of the Church. Sanctity follows on from Holy Communion. The ascetic struggles of the saints are not an aim but a means which leads to the aim, which is Eucharistic communion, the most perfect and complete union with the Holy One. In the Lord’s prayer, the ‘Our Father’, we see that sanctification is associated with the Kingdom of God. We ask that His Kingdom come into the world so that everyone can praise Him and can partake of His sanctity and His glory, which is what we call ‘deification’.

The Kingdom of God and deification are an eternal extension of the Divine Liturgy within space and time, as Saint Maximos the Confessor writes. By taking part in the Divine Eucharist, the saints become gods by grace, but they’re aware that ‘they have the treasure in vessels of clay’ and they see ‘through a glass darkly’. They await and expect the time when the gate of heaven will open and they’ll see God ‘as He is’. Their struggle against the passions and the demons is continuous and they believe that everyone else will go to Paradise except them. They know their insignificance and unworthiness, they don’t believe in their moral superiority and worthiness and, with the humility which they feel, they see others as saints, especially when these people render them honours. This is due to love, which is the one thing which will remain in the Kingdom of God.

An example of their love for God is their personal struggle to observe His commandments. Submission to the will of God cleanses people of their passions and prepares the place for grace to take up its dwelling. All the saints are characterized by an attitude of asceticism and self-sacrifice. According to Saint Isaac, the ascetic life is the mother of sanctification ‘from which is born the first taste of the sense of the mysteries of Christ’. Or, as Saint Maximos the Confessor puts it: ‘By their voluntary mortification, denying all evils and passions… they have made themselves pilgrims and strangers to life, fighting boldly against the rebellions of the world and the body… and have preserved the honour of their soul’.

Such a vessel of grace and dwelling-place of the Holy Spirit, was Elder Iakovos Tsalikis, one of the most important and saintly personalities of our day, a great and holy Elder, a true friend of God.

He was a living incarnation of the Gospel, and his aim was sanctification. From early childhood he enjoyed praying and would go to different chapels, light the icon-lamps and pray to the saints. In one chapel in his village, he was repeatedly able to speak to Saint Paraskevi. He submitted to God’s call, which came to him when he was still a small child, denied himself and took up the Cross of Christ until his last breath. In 1951, he went to the Monastery of Saint David the Elder, where he was received in a miraculous manner by the saint himself.

He was tonsured in November 1952. As a monk he submitted without complaint and did nothing without the blessing of the abbot. He would often walk four to five hours to meet his Elder, whose obedience was as parish-priest in the small town of Limni. The violence he did to himself was his main characteristic. He didn’t give in to himself easily. He lived through unbelievable trials and temptations. The great poverty of the monastery, his freezing cell with broken blinds and cold wind and snow coming in through the gaps, the lack of the bare essentials, even of winter clothing and shoes, made his whole body shiver and he was often ill. He bore the brunt of the spiritual, invisible and also perceptible war waged by Satan, who was defeated by Iakovos’ obedience, prayer, meekness and humility. He fought his enemies with the weapons given to us by our Holy Church: fasting, vigils and prayer.

His asceticism was astonishing. He ate like a bird, according to his biographer. He slept on the ground, for two hours in twenty-four. The whole night was devoted to prayer. Regarding his struggle, he used to say: ‘I do nothing. Whatever I do, it’s God doing it. Saint David brings me up to the mark for it’.

His humility, which was legendary and inspiring, was his main characteristic. The demons which were in the possessed people who went to the monastery cursed him and said: ‘We want to destroy you, to neutralize you, to exterminate you, but we can’t because of your humility’. He always highlighted his lack of education, his inadequacies and his humbleness. It was typical of him that, when he spoke, every now and again he’d say: ‘Forgive me’. He was forever asking people’s forgiveness, which was a sign of his humble outlook. Once, when he was invited to visit the Monastery of Saint George Armas, where the abbot was the late Fr. George Kapsanis, he replied: ‘Fathers, I’m a dead dog. What will I do if I come to see you? Pollute the air?’ He always had the sense that he was a mere nothing.

And when he became abbot he always said that he wasn’t responsible for what happened in the monastery: ‘Saint David’s the abbot here’, he maintained. When he served with other priests, he went to the corner of the altar, leaving them to lead the service. When they told him: ‘This isn’t right, you’re the abbot of the monastery’, he’d reply: ‘Son, Saint David’s the abbot here’.

Although he didn’t seek office, he agreed to be ordained to the diaconate by Grigorios, the late Bishop of Halkida, on 18 December 1952. The next day he became a priest. In his address after the ordination, the bishop said: ‘And you, son, will be sanctified. Continue, with God’s power, and the Church will declare you [a saint]’. His words were prophetic. He was made abbot on 27 June, 1975, by Metropolitan Chrysostomos of Halkida, a post he held until his death.

As abbot he behaved towards the fathers and the visitors to the monastery with a surfeit of love and understanding and great discernment. His hospitality was proverbial. Typical of him was the discernment with which he approached people. He saw each person as an image of Christ and always had a good word to say to them. His comforting words, which went straight to the hearts of his listeners, became the starting-point of their repentance and spiritual life in the Church. The Elder had the gift, which he concealed, of insight and far-sight. He recognized the problem or the sin of each person and corrected them with discretion. Illumined by the Holy Spirit he would tell each person, in a few words, exactly what they needed. Saint Porfyrios said of the late Elder Iakovos: ‘Mark my words. He’s one of the most far-sighted people of our time, but he hides it to avoid being praised’.

In a letter to the Holy Monastery of Saint David, the Ecumenical Patriarch, Vartholomaios, wrote: ‘Concerning the late Elder, with his lambent personality, the same is true of him as that which Saint John Chrysostom wrote about Saint Meletios of Antioch: Not only when he taught or shone, but the mere sight of him was enough to bring the whole teaching of virtue into the souls of those looking at him’.

He lived for the Divine Liturgy, which he celebrated every day, with fear and trembling, dedicated and, literally, elevated. Young children and those with pure hearts saw him walking above the floor, or being served by holy angels. As he himself told a few people, he served together with Cherubim, Seraphim and the Saints. During the Preparation, he saw Angels of the Lord taking the portions of those being remembered and placing them before the throne of Christ, as prayers. When, because of health problems he felt weak, he would pray before the start of the Divine Liturgy and say: ‘Lord, as a man I can’t, but help me to celebrate’. After that, he said, he celebrated ‘as if he had wings’.

One of the characteristic aspects of his life was his relationship with the saints. He lived with them, talked to them and saw them. He had an impressive confidence towards them, particularly Saint David and Saint John the Russian, whom he literally considered his friends. ‘I whisper something in the ear of the Saint and he gets me a direct line to the Lord’. When he was about to have an operation at the hospital in Halkida, he prayed with faith: ‘Saint David, won’t you go by Prokopi and fetch Saint John, so you can come here and support me for the operation? I feel the need of your presence and support’. Ten minutes later the Saints appeared and, when he saw them, the Elder raised himself in bed and said to them: ‘Thank you for heeding my request and coming here to find me’.

One of his best known virtues was charity. Time and again he gave to everybody, depending on their needs. He could tell which of the visitors to the monastery were in financial difficulties. He’d ask to speak to them in private, give them money and ask them not to tell anyone. He never wanted his charitable acts to become known.

Another gift he had was that, through the prayers of Saint David, he was able to expel demons. He would read the prayers of the Church, make the sign of the Cross with the precious skull of the saint over the people who were suffering and the latter were often cleansed.

He was a wonderful spiritual guide, and through his counsel thousands of people returned to the path of Christ. He loved his children more than himself. It was during confession that you really appreciated his sanctity. He never offended or saddened anyone. He was justly known as ‘Elder Iakovos the sweet’.

He suffered a number of painful illnesses. One of his sayings was, ‘Lucifer’s been given permission to torment my body’. And ‘God’s given His consent for my flesh, which I’ve worn for seventy-odd years, to be tormented for one reason alone: that I may be humbled’. The last of the trials of his health was a heart condition which was the result of some temptation he’d undergone.

He always had the remembrance of death and of the coming judgement. Indeed, he foresaw his death. He asked an Athonite hierodeacon whom he had confessed on the morning of November 21, the last day of his earthly life, to remain at the monastery until the afternoon, in order to dress him. While he was confessing, he stood up and said: ‘Get up, son. The Mother of God, Saint David, Saint John the Russian and Saint Iakovos have just come into the cell’. ‘What are they here for, Elder?’ ‘To take me, son’. At that very moment, his knees gave way and he collapsed. As he’d foretold, he departed ‘like a little bird’. With a breath like that of a bird, he departed this world on the day of the Entry of the Mother of God. He made his own entry into the kingdom of God. It was 4:17 in the afternoon.

His body remained supple and warm, and the shout which escaped the lips of thousands of people: ‘Saint! You’re a saint’, bore witness to the feelings of the faithful concerning the late Elder Iakovos. Now, after his blessed demise, he intercedes for everyone at the throne of God, with special and exceptional confidence. Hundreds of the faithful can confirm that he’s been a benefactor to them.