In

his address to the Federal Assembly [on December 12,

2012.—Trans.], President Vladimir Putin stated:

“It is painful for me to say this, but I must

say it: Russian society is experiencing an evident

deficit of spiritual bonds.”

Архимандрит Тихон (Шевкунов)

The dissociation between “fathers and sons,” the lack of understanding among people even of the same generation, and sometimes also the loss of Russia’s traditional moral values… Until this year we hadn’t hear anything like this from the leaders of our government.

Whether we like it or not, after the Soviet period with its coercive ideology, we hurled ourselves, as usual, in the opposite direction: in this case, towards complete ideological confusion and ambiguity of meaning and purpose. While maintaining every aversion to coercive ideology, more and more people are gradually coming to the conclusion that the opposite extreme, a completely de-ideologized state, is spiritually weak and simply unsustainable.

So what instead? A new ideology?

That’s just what I wouldn’t want at all: an ideology labored over behind desks and obligatory for all. Fortunately, however, in the realm of human convictions and worldviews there are things that are much more significant and effective than any ideology.

For example?

Eternal values.

For people today that sounds a little too passionate. Perhaps it might be better to say “core values”? That’s what people today say should be actively cultivated when talking about Russia’s youth policy.

And may I ask which “core values” are most in demand among young people today?

We know this from numerous opinion polls. Health comes first, then quality of life and family, then money and material goods. Security. The ability to find lucrative, interesting work. Then friends. And, finally, love for the Motherland.

Well, if these are indeed the principles values of today’s young people, then our position really is worse than can be imagined. After all, if we translate this hierarchy of values from the language of sociology into Russian, this is what we hear: “Guarantee me a quality education, lucrative work, security, decent housing, and everything needed for good health—and then my friends and I will love the Motherland.”

I have absolutely no intention of moralizing. Everything that the sociologists have enumerated represents the natural and normal desires of most people. Only one thing is unclear to me: why, as has been mentioned, are the efforts of the youth policy of an entire government dedicated to cultivating the desire to receive quality housing? Or to nurturing patiently the undisguised striving for higher pay? Obviously, when we speak of the weakening of “spiritual bonds,” we have something else in mind.

“Eternal values,” after all?

It appears that way. Neglecting and ignoring them leads to tragic ruptures and lack of understanding between people and generations. Recall Shakespeare’s words: “The time is out of joint” [Hamlet, Act 1, scene 5.—Trans.].

Yes, higher values: mercy, kindness, courage, sacrificial love for people and the Fatherland, wisdom, loyalty, generosity, fairness, and modesty… This is not even to mention faith in God and the discovery of His plan for the world and man. It’s these spiritual and moral qualities that most parents most want to see in their children. And it’s their nurturing and cultivation that should probably be the object of youth policy. But here’s the problem: neither moral teaching nor the most correct kind of preaching has any positive effect whatsoever. Moreover, they provoke a persistent and prolonged allergy.

In that case, what do you think today’s youth policy should be?

I don’t know what to say about today’s youth policy, but let’s recall that of ancient Greece.

The ethical basis and foundation of ancient Greek society was the hero, whether mythical or completely real. Such were Pericles, Alexander the Great, and the heroes of art and philosophy: Homer, Phidias, and Plato.

|

| А. Патраков. Муций Сцевола в лагере Парсены |

Byzantium, in the ethical sense, was also a civilization of heroes. One could read about them in special books called the “Lives of the Saints.” In this society, it was heroes of the spirit that were primarily sought after. In medieval Europe the knight was the hero. In ancient Russia they were the saints and the warrior-knights. We can find our own heroes in both recent and contemporary history—and this isn’t even to mention the recent Soviet period, which was thoroughly permeated with the cult of both genuine and counterfeit heroes.

Heroes are bearers of those important and eternal values—of nation, culture, and civilization—of which we were just speaking. But, more importantly, they are more than just bearers. Society assigns them a task that is beyond the strength of anyone else: to transmit these values effectively from generation to generation, from heart to heart. No moralizing, edifying sermons, seminars, or “Seliger forums” will accomplish this task without such genuine bearers of higher values. The pedagogical function of heroes lies in the continuation of their particular service even many centuries after their deaths. It is no accident that Plutarch’s Parallel Lives (biographies of great Romans and Greeks) was studied, for example, in Russian gymnasia right until the Revolution, when completely different heroes came to replace the old ones.

And what is happening today with heroes?

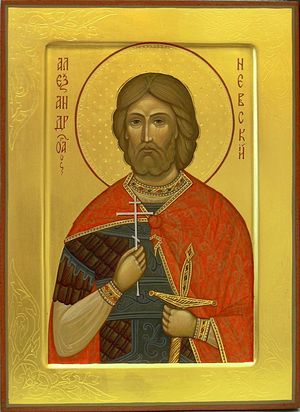

|

| Икона святого благоверного князя Александра Невского. Иконописная мастерская Екатерины Ильинской / icon-art.ru |

Generally speaking, “de-heroization” is, within reason, a positive and sometimes even necessary process that takes place from time to time in various countries and cultures, when the winds of history have carried away the husk and shell of the pantheon.

But in our case in Russia, this revision has been undertaken by the “creative” class and the “right-thinking” society of highly progressive amateur historians. As a result of this purge, conducted with Bolshevik ruthlessness, we have been left without any national heroes at all. They have all been overthrown. They have all been turned into ruthless monsters, scum, scoundrels, cowards, perverts, and unscrupulous opportunists. The methods used are slander, cynical and merciless mockery, and the distortion of facts. In scholarship, it is bias. In collecting facts, it is forgery and the methods of the paparazzi. And all this, of course, comes under the pretext of “fighting for the truth” and the reverent desire to reveal to us, the blind and deceived, the truth about ourselves.

I recently went to a bookstore in central Moscow. In the most prominent place, among the bestsellers, was the latest reprint of Vladimir Rezun’s lampoon of Marshall Georgy Zhukov (1896-1974). [Rezun writes under the pen name of Viktor Suvorov; the book in question is Shadow of Victory—Trans.] Or take another example: for more than a year or two the idea has blown about that “your Alexander Nevsky” was nothing more than a commonplace time-server, a toady of the Tartar princes. And they even try to defame Pushkin as a talentless vulgarian!

But there is a good bit of factual evidence regarding Zhukov’s brutality.

Both Russian and Western academic scholars have long ago completely dismantled Rezun’s “historical” concepts. But this isn’t really the point. Any military leader without exception can be accused of brutality. Recall Pushkin’s words:

Let the hero keep his heart! What

Will he be without it? A tyrant…

|

| V. Tropinin. Alexander Pushkin. |

Rezun’s book and the ensuing campaign is the clearest example of a concerted international and domestic effort to turn inside-out not only the history of the Second World War, but our national mentality as well. The suggestion, implicitly or explicitly, is this: if your great heroes were in fact more often than not monsters and freaks, then what kind of country is this? What kind of nation? Who are you yourselves?

From recent history, it seems that only two heroes have been left: the aged academics Dmitry Likhachov (1906-1999) and Andrei Sakharov (1921-1989) with their opposition to the disintegrating Soviet government. True, there was also Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1918-2008), but in his final years, in the opinion of the “creative class,” his writing was somehow off and he was expelled from their society.

However, the “creative class” does still offer us some modern heroes: namely the “heroes” of glamour. They bear and successfully transmit “values” to the young that are diametrically opposed to higher values: instead of modesty, brazen conceit; instead of nobility, pettiness; instead of nobility, demonstrative opportunism and commercialism. And so on down the list.

Then where in our country can we find real heroes?

That’s the eternal question! Aleksander Griboyedov’s character Chatsky [in Woe from Wit. —Trans.] was already tormented by this:

Where, show us, are the fathers of the Fatherland,

Whom we must take as examples?

Only, let us recall when it was that Chatsky cast this rebuke upon Russia. It was in 1827, it seems, when Griboyedov read the completed manuscript in Petersburg. Could it really be that no one could be found who could serve as a noble model and lofty “example”?

But it was in just those years that Pushkin’s genius was blossoming. Yevgeny Baratynsky (1800-1844) and Vasily Zhukovsky (1783-1852) were creating their poetry. Nikolay Karamazin (1766-1826) performed the learned and literary feat of publishing his History of the Russian State, which was written in contemporary literary Russian. Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen (1778-1852) and Mikhail Lazarev (1788-1851) discovered Antarctica in 1820. In painting, there were Alexey Venetsianov (1780-1847), Karl Bryullov (1799-1852), and Orest Kiprensky (1782-1836). In music, there were Mikhail Glinka (1804-1857) and Alexander Alyabyev (1787-1851). This is not even to mention our great soldiers: the generals, officers, and soldiers who expelled Napoleon and reached Paris! What, can’t they be “taken as examples”? And Mikhail Speransky (1772-1839) and Fedor Uvarov (1773-1824)? And indeed the Decembrists, if someone wanted to take them as an example, were also at hand, so to speak.

How can we reply to people, like Chatsky, who are always thinking about Russia? What kind of remarkable shortsightedness is this? The answer is simple, and was given to us by the very same Alexander Pushkin in one of his letters to Pyotr Vyazemsky (1792-1878). He wrote of the main character of Woe from Wit: “Chatsky is by no means a smart man!”

There are no heroes… But in the last two years alone our soldiers have thrown themselves on grenades to save combatants. Do we remember their names?

Without looking online, no.

|

| Major Sergei Solnechnikov. |

What must we do with regard to them?

“Must” is not the best word. When we were speaking of higher values, we didn’t mention one of the highest and noblest of human qualities: gratitude. There are very few lofty souls that cultivate this rare and beautiful feeling in themselves. The skill of feeling sincere gratitude needs to be learned patiently and (what is especially important) delicately by both children and adults. One cannot demand gratitude towards oneself—that is flat-out vulgar—but one can inculcate in people the ability to be grateful to those who are truly deserving, which is vitally important.

There’s only one commandment for which God promises a very specific reward for fulfilling: Honour thy father and thy mother: that thy days may be long upon the land [Exodus 20:12; cf. Deuteronomy 5:16.—Trans.]. The same applies to the life of nations and societies. Take a look at how many centuries and even millennia countries have survived in which the veneration of ancestors and national heroes has been established as an inviolable tradition and ubiquitous custom, regardless of whatever cataclysms may have occurred. In contrast, as soon as a country begins boldly to destroy the tradition of ancestors and to blacken the best sons and daughters of its people, rapid degradation and collapse are inevitable.

People who embody the best qualities of man, as intended by God, and the best qualities of their people are the greatest treasure of any country. It is they, whether known or unknown, who are Russia’s greatest treasure. No measures taken by state or society can be considered excessive if they’re directed towards gratitude and towards genuine expressions of heroism not going unnoticed.

How often we read in the papers of how, in some provincial town, scoundrels grabbed a girl and dragged her into a car right on the boulevard in front of everyone, but some young nerd intervened—and was killed for it. How many such stories there are… And this youngster is a real, genuine hero! But what do we do about it? Well, there’ll be a small notice in the regional paper. Well, someone will smirk: “It was none of this fool’s business.” Someone else will sympathize: “Poor kid.” And that’s it. And we will return to being astonished by the passivity, cowardice, and indecisiveness of our young people…

It’s unlikely that such stories will come to the attention of governors, for example.

That’s a pity, if that’s indeed the case. The glorification of heroes has always been the task of the higher-ups. Do we want our young people to be brave and not become accustomed to cowardice? Do we want them not to let themselves be pushed around in the army by the passionarity of their eastern peers (who, incidentally, have no shortage of heroes in life)? That they not pass blindly by, one after another, when a girl is being abused? If a monument were built to this fallen “nerd,” a real Russian hero, in the square in which the tragedy took place, and if the governor brought out the entire city to the dedication of this monument, then life for the local scoundrels might no longer seem so secure; the grateful remembrance of heroes can inspire even the timid.

The

governors would tell you that they don’t have

time for such things.

Seargent Evgeny Epov.

Do you think that the President of the United States has so much time? But every year he meets with the firemen who were at the skyscrapers on September 11. He goes personally, because he knows that this one of his most important duties. But why use far-flung examples? March 1 was the anniversary of the heroic feat of the officers and soldiers of the 6th Company [of the 76th Guards Airborne Division from Pskov at the Battle for Height 776 during the Second Chechen War, February 29—March 1, 2000.—Trans.]. President Putin went to Pskov specially to honor their memory. Yes, the story was shown on television. And that was all… The media “did its thing” and forgot about it. But ask young people if they know about the paratroopers’ truly unparalleled heroic deed. Here we have no thought-out, systematic work at all.

Or perhaps here this really isn’t the best time for heroes?

In the twenties and thirties, during the Great Depression in the United States, the situation was, in this regard, even worse than it is now with regard to heroes. It suddenly seemed that there were neither any heroes around nor could there be. So what did the Americans do? Recognizing that having such timeless bearers of important and eternal values was especially needed, they managed to find a hero. And who was he? A simple herdsman: the cowboy. It was on him, on this image, that the burden of transmitting the traditions and spiritual-moral values of the American people was essentially laid.

He bore positive associations: freedom, responsibility, strength, skillfulness …

Yes, and also gratitude, bravery, optimism, patience, kindness, and a sense of justice and sacrifice. For many years he carried out the “hero function” beautifully.

But he was primarily a hero of cinema and culture. For all the educational importance of such examples, it all seems pretty straightforward with them. But what about historical heroes? Right now an intense debate is going on about what textbooks of Russian history should be like. Is a unified approach to such a contradictory subject as history even possible? Isn’t that a utopia?

In the Church of Christ, when a general decision needs to be accepted by people of the most varied positions and views, we are guided by this ancient Christian principle: “First, unity; second, freedom; and in all things, love.”

Might the participants in this discussion take this to heart?

For two decades already we have been searching for a national idea. So far we have decided that this should be patriotism. This is true, of course, but any final formulation, unfortunately, will sooner or later become commonplace; they are always limited, vulnerable, and almost always become annoyingly ideologized. Such formulations inevitably vary depending on changes in either the political system or in the direction of policy. But there are eternal, higher values and human qualities—such as faith, honor, nobility, justice, the pursuit of truth, service, labor in discovering God-given talents, sacrifice, kindness, love for people, and love for one’s Fatherland and fidelity thereto. This isn’t a formulation of the national idea, but rather people who embody the best spiritual qualities present in our thousand-year history, who express the purpose and national idea of Russia. In fact, the people have by and large never formulated their national idea, but have nevertheless unerringly identified its bearers.

Interview conducted by Elena Yakovleva.