Affliction cometh not forth of the dust, neither doth trouble spring out of the ground, reasoned one of the friends of Job the Much-Suffering (Job 5:6). Because for the Christian, woe and trouble is first of all sin and the passion that precedes it, it could be said that passion “does not come from the dust”, and sin “does not grow out of the ground”, but rather springs from the soil of the human heart. The Lord Himself warned us when He said, From within, out of the heart of men, proceed evil thoughts, adulteries, fornications, murders, thefts, covetousness, wickedness, deceit, lasciviousness, an evil eye, blasphemy, pride, foolishness: All these evil things come from within, and defile the man (Mk. 7:21-23). That is, according to the Gospel teaching, not only is sin what is committed in deed, but even the longing for sin—which we call passion—is not altogether innocent by itself and is also a sin.

Having achieved victory in the struggle with their passions, the holy fathers of the Church left us a detailed description of this struggle. Part of this was their scrupulous study of the stages of the passions’ formation in the human soul.

“A thousand-mile journey begins with one step,” say the Chinese. So also every passion begins with one thought, which is called prilog, or “suggestion”. This term describes a thought, but also an image, a feeling, a desire, or a state that suddenly arises in the human soul; however that is not to mean all thoughts or states, but only those aimed at separating us from God. It is not possible to completely avoid prilogs, but it is within man’s power to either accept them or reject them. The Ancient Patericon (sayings of the holy fathers) describes the following incident: “A brother came to Abba Poemen and said to him, “I have many thoughts, and I am in danger from them.” The elder took him outside into the air and said, “Open your collar and lapel, and do not let the wind in!” “I can’t do this,” answered the brother. “If you cannot do that,” said the elder, “then neither can you prevent the thoughts that come to you. But it is your job to withstand them.”

According to patristic teaching, the most reliable method for warring with the passions is to cut them off at the very beginning; that is, to reject the prilog, or suggestion. “If we cut off the thoughts we will also cut off the sin,” taught St. Tkhon of Zadonsk. “Sin comes from thoughts like the tree grows from its roots.”

The next step in the strengthening of the passions in the human soul bears the name “conjunction” and consists in the interchange with the thought. The thought draws the attention of the one being tempted, who is now in danger of being drawn into sin. Therefore, conjunction is not always without blame. If a person feels some pleasure from the interchange, then the will is already inclined towards the sinful thought and is leading the person to the next stage.

That state is called soslozheniem, or “acceptance” of the thought. At this stage happens the complete acceptance of the illicit thought, which attracts and fills the person’s mind, feelings, and will so that sin begins to act in the human soul and prepare it to actually commit the sin in deed.

By lingering in this state a person is taken to the next step, called “captivity”—a state that has a qualitative difference from the former states. If up to that point the person could through his own efforts not only withstand the sinful thoughts, but also overcome them (If thou doest not well, sin lieth at the door. And unto thee shall be his desire, and thou shalt rule over him [Gen. 4:7]), now even the very desire to abandon the sinful thought disappears. If this comes up, then the person is no longer capable of getting rid of the illicit desire that has taken him over—unless he have some outside help.

The final step of this ladder into the abyss is the passion itself, which paralyzes the will, and like a kind of inner despot draws the person into sin. Incidentally, even if the passion does not result in the deed it is nevertheless destructive and requires great effort, prayer, and both divine and human aid to be rid of it.

The venerable Abba Dorotheos illustrated the difficulty in struggling with rooted passion through the following story: “A great elder was walking with his disciples in a certain place where cypresses grew, both large and small. The elder told one of his disciples to pull up a cypress. That cypress was small, and the brother pulled it up quickly with one hand. Then the elder pointed to another one larger than the first and said, ‘Pull up this one also.’ The brother wrenched it back and forth with both hands and finally uprooted it. Again the elder pointed to another, even larger tree, and the brother pulled it out with great effort. Then he showed him yet another, yet larger tree, and the brother yanked it about this way and that, and although he worked hard and sweated over it, he could not tear it out. When the elder saw that he did not have the strength to do it, he asked another brother to rise and help him. The two of them were barely able to tear out the tree. Then the elder said to the brothers, “You see, brothers, it is the same with the passions. While they are small, if we want we can easily root them out. But if we are careless about them when they are small, they will gain strength, and the stronger they become the more effort is required of us to uproot them. When they have become very strong in us, then even with great labor we will not be able to tear them from ourselves, unless we receive aid from certain saints who help us according to God.”

Because the lingering in sin and sinful thoughts becomes worse for the person than the sin itself, the holy fathers call us to go to confession as quickly as possible, even if the fall is repeated many times. In the Ever-memorable stories of the ascetic saints and blessed fathers we find the following: “A brother asked Abba Sisoes, “What should I do, abba? I have fallen.” The elder answered, “Rise up.” The brother said, “I rose and fell again!” “Rise up again,” the elder answered. The brother again asked, “How long will this go on?” “Until you are taken from this life, either good or depraved,” said the elder. “For in whatever state you will be at that time, that is how you will be when you go there [to the next life].”

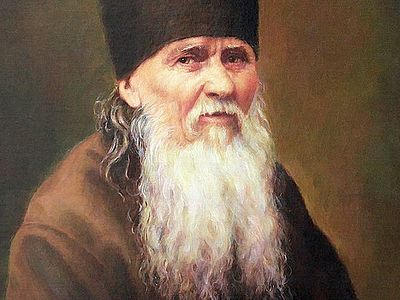

The question may arise as to why the majority of us not do this; that is, why don’t we have recourse to repentance immediately, right after committing a sin? And even if we repent, it is rare if we do not return, as the Scriptures say, “to our own vomit” (cf. Pet. 2:22). St. Ambrose of Optina used to complain, “What times have now come! It used to be that when someone sincerely repented of his sins he would exchange his sinful life for a life of goodness. But now it often happens that a person tells all his sins in detail at confession, and then goes and does what he always did.”

Probably this happens by force of our inner division, our disintegration, which in turn leads to the inability to make a willful resolution—that is, to a lack of resolve. It is namely this lack of resolve, according to the teachings of St. Seraphim of Sarov, that does not allow us to imitate the ancients. This resolve must be shown in the very early stages of the passion’s development—against the prilog, or suggestion. If our indecision does not allow us to take this comparatively easy but necessary action, our strength will be spent on the struggle with the passions, which can grow to monstrous proportions.

How to cut off a suggestion at its very inception is something that everyone has to decide for himself. For example, Empress Catherine II had a rule never to say anything while angry, but rather to wait until she was in a peaceful disposition; and in order to ease the difficulty of silence, she literally filled her mouth with water. St. Moses of Optina did a similar thing. He would not bring guilty monks to reason right away, but only after they had forgotten to some extent what they had done.

Of course, the holy fathers taught that prayer is the most necessary and effective means of conquering thoughts. Here is what St. John the Dwarf writes: “I am like a man who sits under a tall tree and sees that that a multitude of beasts and snakes are coming towards him. If he cannot fight them he will climb the tree and be saved. That is what I do: while keeping silence in my cell, I see evil thoughts attacking me. When I cannot fight them I run to God in prayer, and am saved.” But what at first glance looks like a simple exercise is something that a Christian has to learn his whole life.