Source: An Ancient Faith Blog

The feasts of the Jewish liturgical calendar are biblical commemorations, either being commanded by God in the Bible to be observed or otherwise commemorating a biblical event. Why then do Christians not celebrate them?

This question always comes to my mind around Hanukkah, which is a beautiful story surrounding a miracle that occurred at the reconsecration of the Second Temple after the Maccabean revolt and recapture of the Temple Mount. The story is found in the books of 1 and 2 Maccabees, which are included in the canon of the Old Testament for the Orthodox and Catholic churches. The festivals of Sukkot (Tabernacles) and Passover are likewise biblical commemorations.

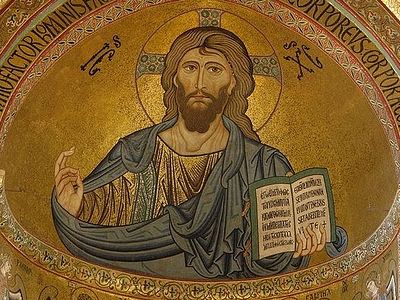

The simple answer to this question is two-fold: (1) Christian feasts are fulfillments of the various Jewish feasts, and (2) because of this, they have a distinctively Christ-centered focus. The Jewish feasts, for Christians, were “shadows and types” of what was to come, which have now been fulfilled by Christ. Therefore, by celebrating the distinctive Christian feasts, we celebrate also what the Jewish feasts foreshadowed. For this reason, the Christian feasts include many references and allusions to the Jewish feasts within the liturgical texts. Lets take a look at a few of these Jewish feasts:

Jewish Feasts Fulfilled in Christ

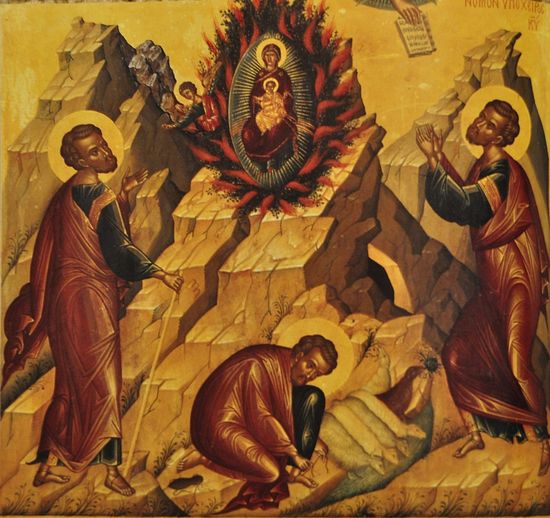

The Feast of Sukkot (Tabernacles): This feast is a harvest festival, occurring just after the Fall New Year (which was moved from an earlier Spring New Year at the beginning of the month of Nisan). The custom of constructing and living in a booth or hut commemorates the Israelites’ conditions as slaves in Egypt and their wandering in the wilderness before entering the Land of Canaan. It was to be a reminder to them that God had brought them from being slaves and nomads to being a great nation. This feast does not have a Christian analogue, nor is it “fulfilled” in any one particular Christian feast. However, we have the monastic tradition, which has seen many people living has hermits in caves and hand-made dwellings. Saints such as St. John the Hut Dweller encapsulate a living embodiment of this feast, and through them we are reminded that we are pilgrims in this world, awaiting a New City, the Kingdom of God (Hebrews 11:13-16).

The Ninth of Av: This feast is a solemn and penitential feast commemorating the destruction of both Temples, the first by the Babylonians in 586 BCE and the second by the Romans in CE 70. As Jesus prophesied in John 2:19, “Destroy this temple, and I will raise it up in three days,” the destruction of the temple is another prophetic image of the crucifixion, thus this feast is subsumed in Great and Holy Friday.

Purim: This feast is a commemoration of the events described in the book of Esther, a novella of sorts, which tells a story of the deliverance of the Jewish people in the Persian capital of Susa. Because this feast is narrowly focused upon a rather ancillary biblical narrative, and because of its national rather than theological character, it does not figure into Christian observances other than in the most broadly symbolic way figuring salvation from godless powers. The story of Esther, like Ruth, who finds salvation for her and her people through marriage, foreshadows the marriage of the Church to her Bridegroom, the Lord Jesus Christ, and therefore by extension, the Unwedded Bride of God, the Ever-Virgin Mary is prefigured as well.

The Feast of Hannukah: As mentioned above, this feast commemorates the reconsecration of the Second Temple after it was recaptured by the Maccabees. The temple has formerly been captured by the Seleucid king Antiochus IV, and a pig was offered upon the altar and a statue of Zeus erected in the Holy of Holies. This event was known as the Abomination of Desolation referred to in the book of Daniel. Since these things effectively desecrated the temple, it had to be consecrated again after its recapture by the Jewish rebels. According to legend, the only pure oil found to consecrate it was one bowl sealed from the days of Samuel the prophet, and it miraculously lasted throughout the 8-day festival. This feast is analogous in many ways to the sacrament of Chrismation, where a newly baptized Christian receives anointing with oil and becomes the Temple of the Holy Spirit. Each Christian, then, is a consecrated Temple of God, a miracle of purification and holiness. The Christian who confesses his or her sins finds that the oil of consecration never runs out, as the mercies of are new every morning (Lam. 3:22-23).

The Day of Atonement: Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, was a very special and solemn day of sacrifice, whereby the sins of the people would be cleansed, and, more specifically, the impurity contracted by the Temple and the city of Jerusalem by virtue of the sins of the people would be cleansed ensuring that the sacrifices offered upon the altar would be acceptable to God and the shekinah glory of God would continue to dwell in the Temple among the people. The Epistle to the Hebrews applies much of the themes and imagery from this feast to the crucifixion of Christ making Holy Friday the Christian equivalent of this feast, though on this feast, no sacrifice (Eucharist) is made, because it was made once and for all by Christ.

The Feast of Passover: The feast of Passover is embedded within the minds and hearts of anyone who has grown up in the Judeo-Christian tradition, especially in the past 50 years, when the Exodus narrative and the institution of passover have become a favorite topic among film-makers. This, of course, is the foundational feast that becomes the Christian commemoration of the Resurrection of Christ. Most of the Christian world (outside of German and English-speaking countries) have not even changed the name of the feast, which was borrowed into Greek from Aramaic as “Pascha.”

The Feast of Weeks (Shavuot): This feast was originally a covenant renewal festival and is therefore perhaps the oldest feast on the Jewish calendar, originating in the earliest phase of Israelite Yahwism. Eventually, this feast became what we know as Pentecost, because it occurs 50 days after Passover (Pascha). Later in Judaism, this feast became a commemoration of the giving of the Law at Mt. Sinai (Ex. 19-20). For Christians, it is also a covenantal renewal festival of sorts, because it commemorates the birth of the Church and the bestowal, not of the Law written on tablets of stone, but the Law of the Spirit written upon the heart.

The Christian Calendar

The feasts of the Christian Church, both East and West, have broadly subsumed the theological themes of the Jewish feasts, giving content and fulfillment to those Old Testament events interpreted as shadows and figures of Christ and his death and resurrection as well as the institution of the Church, his mystical body and temple of the Holy Spirit. As can be seen with the feasts of Passover and Pentecost, the principle at work in their inclusion or exclusion in the Christian calendar is their ability to be interpreted through the lens of Christ and his redemptive work as well as events within the life of Christ and the nascent Christian community that happened on such feasts, again, such as Passover and Pentecost. While the feasts of Weeks and Tabernacles have theological analogues within Christianity, there is no significant event within the life of Christ or the early Church that occurred in association with those feasts, therefore, they do not occupy specific feasts in the life of the Church.

This is an important point to remember, that Orthodox feasts are always rooted in specific historical events in the life of Christ, his mother, or the life of the Church. For example, the feast of the Holy Cross is technically the feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, which commemorates the finding of the Cross in the year 326. The theological veneration of the Cross is festally attached to a historical event. Many of the Jewish feasts were similarly rooted within historical events in the history of Israel and Judah, or, more primitively, they marked the beginning and end of the harvest cycle.

Therefore, even though Christians do not celebrate the Jewish feasts explicitly, we nevertheless affirm their goodness. The very fact that Christians have a festal calendar at all is rooted within Christianity’s historical roots within ancient Judaism. However, we must recognize that the Jewish feasts, for us, are shadows and types of what was to come in Jesus Christ, so that what we celebrate now is both the fulfillment and the fullness itself of these feasts, in that through them, we commune with Christ in the Holy Eucharist and participate mystically in those events, which become for us timeless sources of the revelation of the knowledge of God.