Source: Orthodox-Reformed

Bridge

By Robert Arakaki

Calvinism’s Western Roots

While double predestination is closely associated with Calvin, it is not unique to him. It was also held by some medieval theologians. Gregory of Rimini (d. 1358) taught: “Just as God has predestinated from eternity those whom he willed to, not on account of any future merits, so also he has condemned from eternity those whom he will to, not on account of their future demerits” (in Pelikan 1984:31). Calvin stands out with respect to the clarity and rigor with which he described and applied the doctrine of double predestination (Pelikan 1984:222).

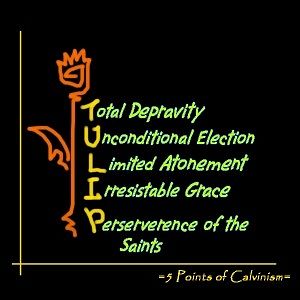

Likewise, the Calvinist vs. Arminian conflict that led to TULIP is not new. Similar tensions can be found in medieval theology. Medieval theologians like Thomas Bradwardine and Gregory of Rimini accepted the doctrine of absolute predestination, whereas Duns Scotus and William of Occam rejected it (Pelikan 1984:28-35; Oberman 1963:187; Barth 1922:52). What makes TULIP Protestant is the fact that it arises from the monergism underlying sola fide (justification by faith alone).

Monergism vs. Synergism

The driving force for Reformed theology is the passion to uphold God’s sovereignty. Reformed Christians glory in God’s sovereignty over all creation and especially with respect to our salvation. The Canons of Dort stresses that God “produces both the will to believe and the act of believing also” (Third and Fourth Head: Article 14; see also Article 10). They believe that any tempering of the divine sovereignty would detract from the glory of God. The German Reformed theologian, Philip Schaff notes:

Augustin and Calvin were intensely religious, controlled by a sense of absolute dependence on God, and wholly absorbed in the contemplation of his majesty and glory. To them God was everything; man a mere shadow(1910:539).

What we see here is what Robin Phillips calls a zero-sum theology. The term comes from game theory. In a zero-sum game there is a fixed amount of points which means that one player’s gain can only come from the other player’s loss. Similarly, in a zero-sum theology for any human to possess the capacity to freely love and have faith steals glory from God.

A zero-sum mentality towards grace assumes that God can only be properly honored at the expense of the creation, and where this orientation is operational it feels compelled to limit or deny altogether the important role of instrumental causation in the outworking of Providence. The zero-sum mentality is thus highly uncomfortable acknowledging that God’s decrees are outworked through secondary means, and prefers to emphasize the type of “immediate dependence” upon God that bypasses as much human instrumentality as possible.

This belief can be seen in the Canons of Dort’s rejection of errors in the Fifth Head Paragraph 2: “…which it would make men free, it make them robbers of God’s honor.” In this approach God’s grace occupies a preeminent role in our salvation and our response a negligible role. Man becomes more an instrument of an omnipotent deity than a free agent cooperating with divine grace. Free will exists, but only for mundane matters, not in relation to spiritual matters (Institutes 2.5.19).

This makes Reformed theology fundamentally monergistic in its soteriology. Monergism is the belief that there is only one (monos) efficient cause (ergos) in our salvation: God and God alone. The alternative approach is synergism, the belief that salvation is the result of human will cooperating or working with divine grace (syn = with, ergos = energy, effort, cause). Thus, where Orthodoxy’s synergism allows for human free will or choice in salvation, Calvinism’s monergism excludes it.

Synergism

Was not our ancestor Abraham considered righteous for what he did when he offered his son Isaac on the altar? You see that his faith and his actions were working together, and his faith was made complete by what he did.(James 2:21-22, NIV; emphasis added)

An anonymous monk described aptly how the Orthodox understanding of synergism maintains the sovereignty of God.

The incorporation of humans into Christ and our union with God requires the co-operation of two unequal, but equally necessary forces: divine grace and human will (in Ware The Orthodox Church pp. 221-222).

Addressing the Western and especially the Calvinist concern that Orthodox synergism may attribute too much to human free will and too little to God, Ware wrote:

Yet in reality the Orthodox teaching is very straightforward. ‘Behold, I stand at the door and knock; if anyone hears my voice and opens the door I will come in’ (Revelation iii, 20). God knocks, but waits for us to open the door – He does not break it down. The grace of God invites all but compels none. (The Orthodox Church p. 222)

The Orthodox understanding upholds God’s sovereignty in our salvation. Not only does God take the initative in the salvation of Man and all Creation, He does the biggest and greatest part, the part man cannnot do. This critical and absolutely necessary action of God, however, in no way precludes man’s response. Note how far the Orthodox position on synergy is removed from the Pelagian heresy.