April 20, 2015

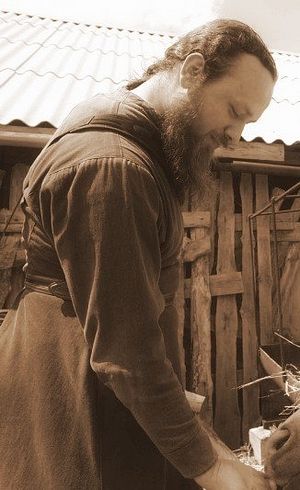

A video of an Orthodox hieromonk tortured by the “volunteer Ukrainian army has been posted on the internet site of Ukrainian journalist Anatoly Shariy. Fr. Theophan (Kratirov) of the Holy Dormition-St. Nicholas Vasilievsky Monastery (the Donetsk diocese of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, Moscow Patriarchate) was abducted on March 3, 2015 by the Ukrainian army and only recently released.

The exhausted and tormented Fr. Theophan related in the video how he was abducted, handcuffed, incarcerated in a basement showing traces of recent torture, and then himself tortured by members of the “volunteer” Ukrainian army. Throughout his imprisonment he had no idea why he had been arrested, and only afterwards did he learn that a local alcoholic in an inebriated state had gone to the Ukrainian authorities and told them that the monastery was hiding the deposed Ukrainian president, Victor Yanukovich, along with his supposedly absconded wealth. The Ukrainian soldiers forced him to write testimony against himself and the monastery.

The Holy Dormition Monastery was founded in 1998 in the Donetsk region, by the locally venerated elder, Schema-Archimandrite Zosima (Sokur). Fr. Zosima was staunchly against any schisms in the Ukrainian Orthodox Church. The monastery is located in a Ukrainian-occupied area.

The video, posted here in Russian, takes some effort and prayer to listen to. In it Fr. Zosima relates in detail his own ordeal and that of other eastern Ukrainian captives. Journalist Anatoly Shariy comments at the beginning that he has released the video for the benefit of Amnesty International, which is now collecting evidence, including from the internet, on cases of torture perpetrated in the Ukrainian conflict.

“On March 3,” Fr. Theophan relates, “I was in a house located outside the monastery territory when a group of armed men in masks broke in and began shouting, ‘Who are you aiding? You’re helping the Russians…’” As he verbally defended himself, the rest of the gang rifled through the belongings kept in the house and took whatever interested them. They ordered him to open all the other rooms, and then took him outside to a waiting bus. He was taken to another meeting point, transferred to another vehicle, then driven to a location outside the city of Mariupol. “It was an exceedingly dismal place,” he comments. Thrown into a basement “cell”, he could see on the floor a huge pool of blood that had been haphazardly swept. “I don’t know whether a man was killed there or just badly beaten, but it was obvious that he lost nearly all his blood.”

This, however, was only the holding chamber before the torture chamber. The worse was yet to come. “It is terrifying when they tie your hands, throw a sack over your head, and take you away. This means they are now going to torture you. This is what they did to me.” He was taken across the corridor to the “shooting range”. The man who led him, who he could not see because of the bag over his head, had a western Ukrainian accent, more precisely from the area of Ternopyl. “If you don’t tell us what we want to hear, we’ll take you to the ‘volunteers’, he said. “You don’t want to be an invalid all your life, do you? You don’t want to stay there ‘forever’, do you?” he was threatened.

“He was interested in knowing where I was from,” says Fr. Theophan. “I told him I was from the monastery, etc. ‘That’s the Moscal [derisive name for people from Moscow] Church! What are they doing here on Ukrainian land?’ I told him that the Church has been here since ages past, when there wasn’t a Ukraine, when it was [part of] a large [Russian] empire.” But there was no talking with him sensibly, and the man only went on with his pro-Western rant. Then another came in, whose voice was the same as the man who arrested him, saying, “What kind of hieromonk are you? You talked on the phone with separatists!” The man went on to boast about his own piety. “I have been fasting for six years now! I pray!...” In fact, Fr. Zosima had seen him on occasion in the monastery church, although he was not a local. The voice of this praying, fasting, church-goer was the voice Fr. Theophan would soon hear as he was tortured at his hands.

The torture chamber had an opening in the ceiling for observation. He was now in it, with handcuffs on his wrists and a bag on his head. The handcuffs were actually more like stocks, which prevented any circular movement of the hands. Whenever he gave an answer that the interrogators did not like, he was beaten—first on the kidneys with a baton, and then on the arms, legs, and liver. When this did not bring the desired result, his interrogators laid him on the floor, the handcuffs cutting at his wrists, and water-boarded him, “like in Guantanamo.” With a rag on his face, they poured water over his nose and mouth from a bucket until he began to convulse. He thinks it lasted an hour and a half, but he says that in that place, time is different. There were no windows, and he did not even know whether it was day or night. It could have been longer. When his convulsions began, they told him he would “rest” until the morning, and then he would write his “testimony”.

He was taken into another room where two other arrestees where held, and when these saw Fr. Theophan’s condition they were terrified. “I couldn’t sit or lie down. I was gasping for breath, and delirious. I began having hallucinations.” Observing from above, the torturers asked him what was going on and accused him of faking these manifestations. He was finally laid to rest on the planks and began to doze. The room was cold, and he was wet from head to toe, with water pouring out of his shoes. That night he was taken out to write his “testimony”—“They forced me to write everything,” he admits. It took several hours, because every time he told things as they really were, he was told he was lying; they would pour more water on him and even give him electric shocks.

But apparently Fr. Theophan’s ordeal was nothing compared to what the separatists were made to endure when taken captive. The other prisoners told him that they had witnessed how these people were tortured. Their arms and legs were slashed when they gave the “wrong” answers. At the Donetsk airport, where the Ukrainian volunteer army interrogated prisoners, the separatists were strung up by their hands, which were tied behind their backs. Whenever they gave the wrong answer, the rope was pulled tighter. Fr. Theophan was also told how women were tortured in the cell were he was held. “Metal cables attached to an electrical device were clasped on their breasts and a strong charge was administered until they were brought to a terrible state, and made to talk.”

“When Ukrainian soldiers found separatists wounded on the battle field, they would twist their broken limbs to make it more painful… By the way, Ukrainian doctors refuse to treat wounded separatist soldiers.” (Here we have to insert that there have been many reports in the news of how wounded Ukrainian soldiers have been treated by volunteer medical personnel from eastern Ukraine and Russia, and then released.) Fr. Theophan saw one fighter who had shrapnel lodged in his flesh, which the Ukrainian doctors had refused to remove when it would have been possible to do so without an operation. No medicines are given to them. The wounded soldiers are told, “You are here, but you don’t exist.”

Fr. Theophan goes on to tell how he was taken to Kharkov, then Kramatorsk, where a battle began. Shells were exploding all around, and he didn’t know whether he would make it through alive. Finally he was delivered to the exchange point, and taken to talk with journalists in Donetsk.

“Of course, we are in a very complicated situation,” Fr. Theophan explained when he talked about the drunken accusation made against him and his monastery. “These are the kind of sources they are getting their information from, and acting on it… They call us fakes, saying that we are only dressed up as monks. I have been serving God from an early age, all my life…” The authorities, he feels, are insane. “It’s simply a matter for the psychiatrists.”

Fr. Theophan is only one of the number of priests who have been abducted and beaten or tortured during the conflict in the Ukraine. We sincerely hope that this and other incidents be duly noted and investigated by Amnesty International and other international organizations—not only to protect people from war crimes, but to protect the “fasting and praying” war criminals from their own selves.