St. Ethelbert (also known as Albert or Albright), King of East Anglia and Martyr (in the Eastern tradition—Passion-Bearer), is venerated as the main patron saint of the city of Hereford in western England, as well as of Hereford Cathedral and the local Anglican diocese of Hereford. He is also especially venerated in the counties of Norfolk and Suffolk in eastern England, where 12 ancient churches and several chapels were dedicated to him.

There are a number of relatively similar versions of his life written not earlier than two centuries after his death. His martyrdom was first recorded by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle under 794, which tells how King Offa of Mercia ordered the beheading of King Ethelbert of East Anglia. The following writers of authority living in a later period composed stories or versions of his life: the monk Florence of Worcester (early 12th century), the historian William of Malmesbury (12th century), the monk and writer Osbert of Clare (d. 1158, later Abbot of Westminster), the chronicler Gerald of Wales (c.1146-c.1223), Matthew Paris of St Albans (c.1199-1259) and the minor historian Richard Cirencester (d. early 15th century). Here is the story of St. Ethelbert according to the earliest versions.

He was most probably born in 779 to a Christian family belonging to the ancient royal lineage of East Anglia. His father’s name was Aethelred and his mother bore the name Leofruna. He was brought up in the Christian tradition and obtained an education at the monastery in Bury St. Edmunds. From his childhood Ethelbert was very serious, polite, kind-hearted, and friendly, and was filled with the desire to imitate Christ in everything. At that time most of England was under the control of King Offa of Mercia, who had a great ambition to place all the lands of England and part of Wales under his control, and wanted the Church to be subordinated to the State. A series of massive earthworks that can still be seen near the Welsh border is called “Offa’s Dyke”— to this day a reminder of this ruler’s thirst for power.

When Ethelbert was 14, his father died and the young man was crowned king and started to rule his kingdom. It was in the year 793 or 794 that Ethelbert was offered marriage but the devout king first declined, wishing to keep his virginity. But as he needed an heir, Ethelbert finally agreed. His adviser, Oswald, suggested as a candidate the daughter of King Offa and his Queen Cynethryth of Mercia, Alfreda (also called Etheldritha). Ethelbert and all the court consented; only the saint’s mother, Leofruna, was hesitant as she feared the Mercian family and their dishonesty. Nevertheless, it was decided that Ethelbert would set out for Mercia.

As soon as the young king mounted his horse, a sudden earthquake occurred that made all his companions panic. Leofruna saw in this a sign from the Lord that her son would never return home alive. “Let the will of God be done!” exclaimed Ethelbert. But another sign followed. The sun darkened and such a dense fog rose around, that all who accompanied the king could not see each other or anything near them. Seeing this solar eclipse, the king commanded everybody to kneel and pray together: “May the Lord give us His mercy!” he said. As soon as they offered up a prayer, the fog dispersed.

Memorial column in honor of St. Ethelbert illustrating his life and veneration inside Hereford Cathedral

Memorial column in honor of St. Ethelbert illustrating his life and veneration inside Hereford Cathedral

On their way to Mercia Ethelbert was filled with spiritual joy and asked his companions to sing joyful songs, promising to give his bracelet to the most skillful singer. They started singing spiritual hymns and songs relating his royal lineage. The king took off his bracelet immediately and promised other gifts on his return. Eventually they reached Mercia, deciding to stop at Sutton in present-day Herefordshire. The following night Ethelbert had a strange vision: his palace was in ruins and his mother, weeping, was coming up to him; meanwhile he himself turned into a beautiful bird with golden wings which flew very high to the heavens, where it finally heard the angelic choir glorifying the Most Holy Trinity. Waking up, he asked his adviser Oswald to explain the dream to him. Oswald kept silence for a few moments and then replied: “Oh, king! Whatever happens to you, by the mercy of God all will be for the good”.

Thus, the trusting Ethelbert sent his messengers with gifts to King Offa while he followed behind. Offa, however, believed the wicked false rumors spread by his impious wife Cynethryth that the young king was allegedly coming with the hostile intent to invade the kingdom. As pious Ethelbert was approaching the royal palace, young Alfreda, his would-be betrothed, spotted him from the window. The young princess at once ran to her mother, exclaiming: “Dear mother! King Ethelbert has come! Such a pleasant young man! I would surely marry him!” These words enraged Cynethryth—she hurried to her husband Offa and said to him: “The rumors are true. If this marriage takes place, you will lose your kingdom very soon. So go and offer half of your riches to him who agrees to kill him”.

Ethelbert was welcomed near the palace by Wimbert, the court officer, who (after a conversation with the king) was treacherously going to murder the unsuspecting King of the East Angles. Ethelbert got down from his horse and said he wished to speak with King Offa. Wimbert slyly responded that the king was aware of his arrival and was waiting for him; but he must remove his sword as it was not proper to appear before the king with a weapon in peacetime. The ingenuous Ethelbert gave up his sword and, accompanied by several nobles, proceeded to the king. He came to Offa. The doors were closed. The innocent Ethelbert was then seized, tied and beaten severely. After that Wimbert beheaded Ethelbert with his (the saint’s) own sword. The young Alfreda mourned the loss of her fiancé very bitterly and, unable to endure the callousness of her parents, retired to Crowland in the Lincolnshire marches where she lived as anchoress for 40 years. Famous for her prophecies, Alfreda reposed in c. 835 and afterwards was locally venerated as saint (feast: August 2/15).

Since then Ethelbert has been known and venerated by English people as a martyr, a saint of God who gained abundant divine grace. Although Ethelbert did not die for Christ, he fell victim to evil, being personally very pious, so he is regarded as a passion-bearer. King Offa, who arranged his murder, did not repent (according to most of the sources) and is remembered as a cruel king with a lust for power. It is supposed that the scene of St. Ethelbert’s martyrdom was the royal villa at or near Sutton.

The Mother of God together with St. John the Evangelist and St. Ethelbert of East Anglia - by Peter Murphy

The Mother of God together with St. John the Evangelist and St. Ethelbert of East Anglia - by Peter Murphy

Having martyred Ethelbert, Offa ordered his body to be thrown into the marshes close to the River Lugg, which flows nearby. A pillar of supernatural light appeared above the place many times and many people saw the pillar shining. A spring of holy water rose next to the spot and it cured the sick from many diseases—this well in honor of St. Ethelbert still exists. A short time later a priest had a miraculous vision. In this vision he was commanded to go to the place now known as Marden in Herefordshire and “find an incredible treasure by the River Lugg.” He was also ordered to place the saint’s body on an ox-cart and send it to the site called Fernley near the banks of the River Wye; this site is associated with present-day Hereford. The priest together with his companion Ecgmund found the body of the holy king together with his severed head—they were all in ooze, but an unusual light was issuing from them. The men washed the body, wrapped them in clothes and put them on a cart.

However, as soon as they reached the spot called Lyde, the saint’s head fell from the cart without being noticed. At that time a certain blind man was walking in that area. Suddenly he stumbled on something and the blind man realized it was a human head. Enlightened by the grace of God, he lifted the holy head in his hands and cried out: “O Ethelbert who was murdered by the disgraceful order of Offa! Have pity on me and return me my sight!” And, as he asked for his eyesight with true faith, it was instantly returned to him. Beside himself with happiness, he ran toward the cart with the head-relic in his hand. He overtook it at a spot called Shelwick. He cried: “Stop, stop, priest! I am holding the precious gem that you accidentally lost but owing to which my sight has been restored!” And he told the companions what had happened to him. All of them thanked God for His miracle and continued their way to Fernley.

Already near their destination the cart stopped for a short while, and a holy well gushed forth on that spot immediately. In the past its water healed many people from ulcers and sores. This St. Ethelbert’s well, though it only partly survives, can be found in the city of Hereford to this day, not far from the Cathedral. Finally the wayfarers reached the very place where Hereford Cathedral now stands. Inspired by Divine grace, they decided that the saint’s relics would rest there. Soon afterwards a nobleman named Milfrid built a splendid Cathedral there and placed the holy relics inside it. The first diocese with a small church existed in Hereford as early as 676, and the construction of the first Cathedral containing relics of Ethelbert is dated to about 830.

From that time the veneration of Ethelbert grew. There was a continuous influx of pilgrims from all over the country to the shrine of Ethelbert in Hereford, and there were thousands of cases of healing. Some historians say that the veneration of Ethelbert was so strong that Hereford was second only to Canterbury in the national popularity of shrines in the late medieval era. Wealthy people gave Hereford generous donations and Hereford Cathedral gained fame as a great ecclesiastical center, famous for its scholarly and music traditions from ancient times. Hereford is one of three English cities along with Worcester and Gloucester that first initiated the famous “Three Choirs Festival” (the festival of Church music organized alternately every year since 1724, by choirs of these cities’ Cathedrals).

The shrine of St. Ethelbert was very splendidly decorated. Unfortunately, in 1055 the rebel Elfgar, son of Leofric, Earl of Mercia, sacked Hereford killing some of its inhabitants, and in 1056 Welsh forces burned down Hereford Cathedral and murdered seven clerics defending entry to the church. It seems that the larger part of relics of Ethelbert was destroyed. Nearly at the same time the head of Ethelbert was translated to Westminster in London, where his veneration spread. Athelstan, the last saintly Orthodox bishop of Hereford, who was bishop for over 40 years and for the last 13 years of his life was blind, died in 1056, unable to bear such a loss.

In 1079, construction of the new Cathedral in the Norman Romanesque style began and was completed several decades later (this is the same Cathedral which dominates the city today). Beyond a doubt, the rebuilding of the Cathedral greatly contributed to a revival of veneration of the holy martyr. As was recorded by a historian in about 1140, there was a huge number of wonderful miracles and signs at that time. It was remarkable that though the saint’s main relics were lost, believers kept flocking to Hereford throughout the medieval period, seeking healing of body and soul and asking for consolation—and the prayers of many of them were answered. It is known that Hereford for a long time preserved the tradition of frequent reading of two of the most recognized versions of Ethelbert’s Life at services. On his feast-day (May 20, the commemoration of his martyrdom) antiphons in honor of the saint were sung at Hereford every year; part of a collection of hymns to the saint (to be sung at the service to him) were also found in the 13th-century Catholic breviary of Hereford. St. Ethelbert was widely venerated until the Reformation, when the official veneration of saints in England was prohibited.

In about 1200 the Cathedral received a tiny relic, thought to be a tooth of St. Ethelbert, and this was venerated by many of the faithful. From the end of the 13th century, now Catholic Hereford had two patron-saints: the Martyr Ethelbert and the Catholic Bishop Thomas Cantelupe of Hereford who died in 1282. In spite of the bloody Reformation and its disastrous consequences, today the popular and liturgical veneration of Holy King Ethelbert has been restored. Hereford Cathedral, already some 1000 years old, standing in the picturesque city of Hereford near the River Wye, is dedicated to the Mother of God and St. Ethelbert the Martyr to this day. It is one of only a few English Cathedrals dedicated to an early local saint. The holy king is remembered in several places within the Cathedral, especially in a memorial column (referred to as “St. Ethelbert’s shrine” in the Cathedral guides) with beautiful panels vividly relating the story of the life and veneration of the saint of God. This moving shrine-column, installed not long ago, stands at the entrance to the attractive 13th-century Lady Chapel built in the early English style. A statue of St. Ethelbert as the church’s main patron stands on the right of the high altar; a 14th-century window in the Cathedral depicts the king’s figure. The Cathedral choir’s sculptures comprise, among others, one of St Ethelbert, and finally, there is also a Victorian tile showing the martyrdom of Ethelbert.

Interestingly, today Hereford Cathedral has three saintly patrons: one Orthodox (Ethelbert), one Catholic (Thomas Cantelupe, mentioned above) and one Anglican (the poet, religious writer, ascetic and priest Thomas Traherne: 1637-1674—author of the Centuries of Meditation who served at Credenhill near Hereford and who in spirit was close to Orthodox world-view). Thomas Cantelupe is commemorated in the Cathedral’s north transept where his restored shrine with relics, made of stone and marble, is installed; it is considered to be one of the best preserved early shrines in England. Thomas Traherne is immortalized in the Lady Chapel of Hereford—here the newly renovated chapel of Bishop Edmund Audley of Hereford (c. 1524) contains modern stained glass windows by the painter and stained glass artist Thomas Denny, dedicated to Traherne’s memory and depicting him. (For his spiritual labors Traherne is venerated by Anglo-Catholics as a saint. His name can be found in calendars of many Anglican Churches and his feast-days are September 27 and October 10). Thus Hereford Cathedral has recently substantially restored the veneration (though not in the Orthodox sense, but this is all the same worthy of attention) of its three major patron saints, Orthodox, Catholic and Anglican pilgrims visit this ancient house of God, offer up prayers and lighting candles near the shrines.

Hereford Cathedral is a unique church also because it keeps some other significant and very rare treasures of antiquity: the “Mappa Mundi” (“Map of the World”, dating back to c. 1300), the 8th-century Early English illuminated “Hereford Gospels” with Celtic elements, and “the Chained Library”. The “Map” and the “Library” are located in the Cathedral cloisters and the modern library building. “The Mappa Mundi” is the largest surviving medieval map in the world and one of the best-known early English documents. It is a sort of a mini-guide to holy places of the globe and is (intentionally) spiritually accurate rather than geographically so. The main purpose of this map was to reflect the Christian view of the Creation. For example, Jerusalem is shown in the center of the globe. The map measures 158 x 133 centimeters. The 17th-century “Library”, the largest in the world of this kind, has a permanently updated collection of rare manuscripts, books, documents and archaeological finds. All of its chains, rods and locks are still in perfect condition. The system enables you to take a book from the shelf and read it at the desk, but not to remove it from the bookcase. The Cathedral also boasts a crypt, elegant carvings of stone and wood, monuments to many church figures revered here over the past 1200 years, tapestries, stained glass, the former shrine of St. Thomas Becket, the “chapter” garden and rich ancient Cathedral archives.

Today the places associated with St. Ethelbert’s life and martyrdom still keep his memory and, as it seems to pilgrims who visit them, are filled with his spirit and presence. In western England these places include Hereford with its Cathedral and holy well, as well as Marden—the approximate site of his martyrdom. The Anglican Church dedicated to the Virgin Mary stands there to this day. Though the oldest part of the present structure dates back to the 13th century, the original church here was built as early as the 8th century. This church standing in a beautiful rural setting (Herefordshire is considered by many to be the most rural and agricultural county of all England) still houses the holy well dedicated to St. Ethelbert. The well can be found at the west end of the nave, right inside the church. This holy well is over 1200 years old, and formerly it reputedly healed eye diseases. The Anglican church in the village of Littledean in the county of Gloucestershire in western England is also dedicated to this saint, as well as the Roman Catholic parish church in the Herefordshire town of Leominster.

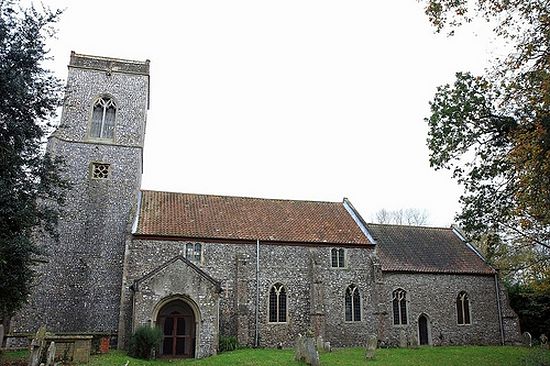

But all the other major centers of his veneration are concentrated in eastern England, in the area of his native kingdom of East Anglia. In the county of Norfolk Anglican churches are dedicated to St. Ethelbert the Martyr in the villages of Alby, East Wretham, and Larling (the 14th-century building), Thurton (the church is Norman), Mundham. The ruins of St. Ethelbert’s Church can also be seen in a spot called Burnham Sutton (also Burnham Market) in this county. In neighboring Suffolk, churches in the following villages bear his name: Falkenham (near the port town of Felixstowe), Hessett (near the town of Bury St. Edmunds), Herringswell and Tannington (the latter two villages are tiny). Most of these churches are very ancient and have been living testimonies of St. Ethelbert’s holiness.

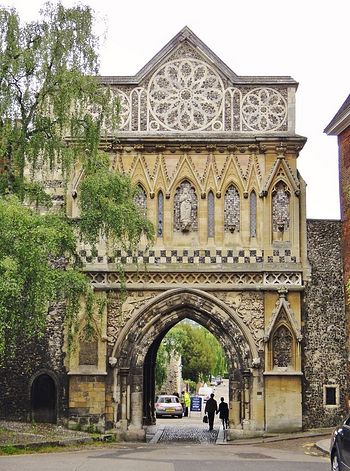

It can be added that a modern church in East Ham in Greater London, built a century ago, is dedicated to the Great Martyr George and St. Ethelbert the Martyr (the name of Ethelbert was added recently at the request of Hereford Cathedral). One of the two main gates to the precincts of the huge and magnificent Norwich Cathedral in Norfolk is named after St. Ethelbert the Martyr. This is the earliest surviving gate to the Cathedral, dating back to the first half of the 14th century. According to tradition, the townsfolk broke down the original gate during the riot of 1272, and then rebuilt the new gate (in honor of Ethelbert) as a penance. The gate is two-storied, and the second storey was formerly used as a chapel in the saint’s memory.

Four coins of the late 8th century minted during the short reign of St. Ethelbert still survive. One of them was discovered in 2014 in a Sussex field with a metal detector: this is an Anglo-Saxon silver penny with the name of King Ethelbert engraved on it. English Christians have never quite forgotten this saint of God. To this day the humble martyred King Ethelbert suggests that English people should recall their distant past, to remember the times when England was part of the Orthodox world, when the true faith and Church of Christ were triumphant in the country—and he is gently calling them to return to that time.

Holy King Ethelbert of East Anglia, pray to God for us!