Cornwall is an English county and an ancient Celtic region in the extreme southwest of England. It is washed by the Celtic Sea (part of the Atlantic Ocean between the southern coast of Ireland and western Brittany) to the north and west, by the English Channel to the south. Cornwall borders the county of Devon in the east over the River Tamar.

It is unknown exactly when Orthodoxy was first brought to Cornwall. According to unreliable medieval legends, St. Joseph of Arimathea may have visited Cornwall together with the Infant Christ. There is no evidence at all to confirm this, but Joseph was a trader and Cornwall has been famous for its tin since time immemorial, so it is not completely impossible. However, in the fourth century Orthodoxy of the “Roman-British” variety was legalized throughout Britain, as elsewhere in the Roman Empire. In the fifth century the first monks arrived in Cornwall and the whole region gradually became Christian. There were many missionaries from Ireland and Wales, as well.

Although a small region, Cornwall over its Orthodox period produced roughly between fifty and sixty individual saints who can be identified, but their number may be greater, given the existence of many obscure saints. Cornwall remained in the Celtic tradition of Orthodoxy and independent from the rest of England more or less until the tenth century. After the Norman Conquest it became Roman Catholic, as all other parts of Britain. The Bible was not translated into the Cornish language until quite recently, and that is why the language has died out, although attempts have been made to revive it.

In the nineteenth century, Cornwall was under the strong influence of Methodism, but a liturgical revival began approximately 100 years ago. Today nearly every town and village of Cornwall has its own patron saint, and there are over 100 holy wells in Cornwall (on average, each English county has three or four local saint, and the number of wells is considerably lower also). Lives of many Cornish early saints were well researched by the Anglican hagiographer Gilbert Hunter Doble (1880-1945) and by our contemporary Prof. Nicholas Orme from University of Exeter. Let us now talk about two saints of Cornwall, one of whom was Irish but moved to evangelize Cornwall, and the other one who was Cornish but left his native land to preach in faraway Scotland. They are Sts. Piran (feast: March 5/18) and Constantine (feast: March 9/22).

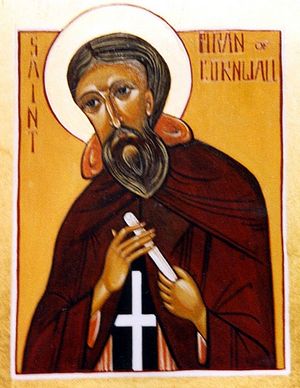

Saint Piran (also Perran) of Cornwall

This saint has been venerated as the patron-saint of tin miners and is one of the patrons of Cornwall together with the Archangel Michael1 and St. Petroc. He is one of the greatest saints of Cornwall and probably one of the earliest; his date of repose is often given in calendars as 480. According to the most popular version, the future saint was born in Ireland; however, according to another version he was born in Glamorgan in Wales. The tradition relates a beautiful story of how Piran ended up in Cornwall. An Irish pagan who hated the young ascetic for his Christian faith tied him to a millstone and threw him down a cliff to the turbulent sea, which at the same moment became calm. Supported by miraculous power, Piran “sailed” on the stone safe and sound until he finally reached the northern shores of Cornwall. The saint took it as a sign from the Lord that he should settle down in this land and bring as many of its inhabitants to Christ as possible. This legend can be interpreted spiritually.

The saint for some time led an ascetic life at Perranzabuloe (meaning “Piran in the sands”) on the Cornish coast. The hermit prayed in a simple chapel-hut in the Irish style, which he built himself of wattle and daub on the extensive dunes, today known as Penhale Sands (a thirty-foot-long chapel was built on this site and dedicated to St. Piran after his repose). Soon the holy man was joined by a large number of local Christians who had been converted by him and other preachers. Together they established a monastery called Lanpiran, which means “the church of Piran”. The saint became the first abbot of that monastery which existed until 1085.

St. Piran is listed among the most successful missionaries who came to Cornwall from Ireland and Wales in the fifth and sixth centuries and enlightened the area. For many years St. Piran lived as a hermit near the present-day town of Padstow. He performed so many miracles and brought so many people to know Christ and the joy of the Gospel that he was loved and venerated by everyone already in his lifetime. Some historians suppose that Piran also served as a bishop and his see was situated in Padstow, although there is no written evidence to support this version. After his death, Piran was deeply venerated in the Celtic regions, especially in Cornwall, Wales (where he may have preached and founded several churches), Ireland and Brittany.

The man of God reposed in Perranzabuloe, where he had a chapel and a holy well (the latter was sadly destroyed in the twentieth century; its waters were famous for healing rickets). He was buried there, but later his relics were divided and distributed among many districts of the country. It is certain that an arm bone of Piran was kept at Exeter Cathedral in Devon where it was annually taken in processions that were accompanied by healing miracles. Another arm was possessed by Waltham Monastery in Essex. His head-relic, silver cross, crozier and a personal copper bell were at one time kept in Perranporth (“St. Piran’s port”).

Throughout the centuries, miners, colliers, and especially tin miners regarded St. Piran as their heavenly protector, and they invoked his name in their prayers, asking him to help, strengthen and bless them in their very hard work. Numerous towns, villages and other places across Cornwall bear the name of Piran; among them are the resort town of Perranporth on the north coast of the county (near the better known port of Newquay) and the villages of Perran Downs (“St. Piran’s downs”) and Perrancoombe.

Thousands of pilgrims visited the miracle-working relics of Piran in the Middle Ages. The church at Perranzabuloe was considered the most popular pilgrimage destination in Cornwall after St. Michael’s Mount. Today Perranzabuloe is a small hamlet near the town of Perranporth. The chapel (referred to as an “oratory” in guide-books), which was built on the site of St. Piran’s hermitage stood here for many centuries; but unfortunately, it was gradually covered by sands (this area consists mainly of sandy beaches) and literally disappeared from view.

This happened after the Reformation when the veneration of all shrines was prohibited and neglect of this kind became possible. In the twelfth or thirteenth century a larger church of St. Piran was built close to the chapel, but further inland. (Presumably the chapel had already been abandoned and lost in the dunes, and so the church was built to replace it). With time the church was considerably enlarged and adorned. However, this church also became a victim of encroaching sands, and by the end of the eighteenth century it became clear that it would be engulfed by sand before long.

Most of the old St. Piran’s Church was demolished and used early in the nineteenth century for the building of the new St. Piran’s parish church in the same village; this church stands there to this day and looks as if it were medieval. Extensive archeological excavations were carried out in the area within the ruins of the old St. Piran’s Church in the nineteenth century and also in 2005; the ruins survive and are visited by pilgrims, and adjacent to them is a large old graveyard. As for the chapel (oratory), this building was unexpectedly and miraculously uncovered in the eighteenth century and from 1843 on thoroughly examined by scientists, archeologists, and historians. For some time the chapel was open to the public, attracting many pilgrims in the twentieth century. It was even was encased into a concrete structure in 1910, purposely built to protect it.

The chapel structure is simple and consists mainly of a chancel and a nave, and the faithful used to bring flowers and lay them on its altar (rebuilt late in the nineteenth century) in past decades. However, the frequent floods, relentless dunes and vandals caused even more damage to the structure, vulnerable as it is. So it eventually fell into ruin and in 1980 it was decided to bury what remained of the chapel in the sands on the same site for the treasure’s better conservation. It was also reported that three human skeletons had been discovered under the floor of the church: one of them well may have been the holy body of St. Piran. Early in 2014, plans to dig up the ruins of St. Piran’s Chapel again—one of the earliest stone churches in the British Isles—were announced; the aim was their better examination and veneration. The excavation work was completed by November of that year.

Between the ruins of St. Piran’s old Church and his chapel, an eight-foot cross in memory of St. Piran was restored for pilgrims to venerate as well. It is said that the fabric of this cross is from the tenth century. This makes this site unique in Cornwall and even in all England as it preserves a shrine dating to the early Celtic period with the continuity of veneration. Orthodox, Catholic, and Anglican believers feel a special atmosphere of holiness and the invisible presence of the saint on this spot.

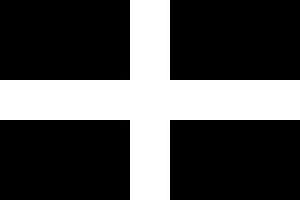

To commemorate the spiritual labors of Piran, annual pilgrimage “marches” to St. Piran’s cross to Perranzabuloe are arranged by the faithful. Hundreds of marchers dress in white, black and golden clothes, carrying “the Flag of St. Piran” in their hands, and leave daffodils by the cross.

St. Piran’s Flag is a white cross on a black background. It symbolizes the Gospel of Christ—the light shining in the darkness, holiness and purity gleaming amid sin and vice. There is an interesting tradition connected with the origins of this flag: Once a white cross miraculously appeared on the hearth that St. Piran used at his home, which had been blackened by soot. A similar legend recounts that Piran reintroduced tin-smelting into Cornwall: One day when he was looking after his fire, Piran saw streaks of silvery metal oozing from the stones he used as a fire-place in the shape of a cross. He shared this story with the locals. From the 1830s, this flag became the official or, rather, semi-official flag of Cornwall, although its first depictions are at least from the fifteenth century. This flag often flies from Cornish buildings, including the Council of Cornwall, and is the symbol of Cornish diasporas abroad.

A host of churches are dedicated to our saint in Cornwall, South Wales and Brittany. Among the Cornish churches bearing his dedication let us mention churches at Perranuthnoe (originally built by him, its other patron is the Archangel Michael); Perranarwothal (also built by him, the present structure is of the fifteenth century; it was here that the well-known English novelist William Golding died in 1993 aged 82); and a Roman Catholic Church in Truro in honor of the Mother of God and St. Piran. A Greek Orthodox parish (the Ecumenical Patriarchate) near the town of Falmouth is dedicated to the Archangel Michael and St. Piran. There have been holy wells dedicated to our saint in the villages of Probus and Perranwell (“St. Piran’s well”), both originally founded by him. In Brittany he is still remembered at Trézélidé, St. Peran, Loperan and Saint-Perran, indicating that the ascetic may have worked there. Notably also, a mountain in the Western Canadian province of Alberta is named Mount St. Piran after this great Celtic saint.

The Day of St. Piran, a co-patron of Cornwall, is still widely celebrated in this county on March 5 (his feast according to the old calendar). It is regarded by many as “the national holiday of Cornwall”, and there has been a campaign to get this day recognized as a Bank holiday for Cornish people. On this day some locals greet each other with the phrase: “Gool Peran Lowen” (“Happy St. Piran’s Day”). The week preceding St. Piran’s Day is called “Perrantide”. Every year Perranporth holds the Celtic festival called “Lowender Peran”. Some native Cornish traditions associated with St. Piran and other saints are being revived in our days. In the case of St. Piran, there is a host of various celebrations and festive events nearly in every community all over the county, including prayers, religious and civic processions, speeches, concerts, plays, parades, walks, parties, decorations, dances, fairs, and even re-enactments of St. Piran sailing from Ireland to Cornwall on a floating stone. St. Piran’s Day is gaining popularity in some communities in the USA as well. St. Piran is also the patron-saint of the Duchy of Cornwall in Cornwall.

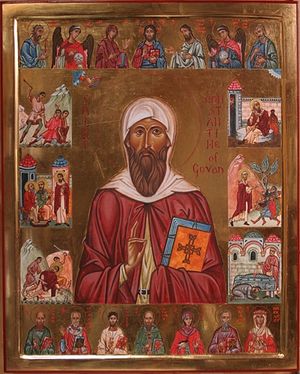

Saint Constantine of Cornwall

This saint is mentioned in the Genealogies of the Kings of Dumnonia, by the Annals of Wales and the Ulster Annals (Ireland), in the eleventh-century Life of St. David of Wales and in other later sources. St. Constantine lived in the sixth century. He was a king or prince of Cornwall, a brother of St. Illtyd and in his youth led an impious life, but with time repented of all his sins and embraced the Christian faith. It was St. Petroc who helped him in this path. The Life of St. Petroc relates that Petroc converted him to the true faith when Constantine was chasing a deer—this scene from his Life was subsequently depicted in art. Thus, Constantine firmly decided to dedicate the rest of his life to the service of God: to spreading the Gospel and founding churches. First he studied at Menevia (Mynyw) Monastery in Wales under St. David, the patron-saint of this country. After that he spent some time in Ireland, and from there moved to what is now Scotland. In Scotland he labored for the glory of Christ for many years, and after fruitful missionary work he was murdered there by thieves. The exact date of his martyrdom is unknown, but some sources give the year 576.

According to tradition, in Scotland St. Constantine was tonsured a monk and ordained a priest, founding churches in the region of Strathclyde with the future city of Glasgow as its center. Notably, he may have founded a monastery in Govan (now a district on the southwestern outskirts of Glasgow) on the bank of the River Clyde, becoming its first abbot. If this medieval tradition is true, it makes St. Constantine one of the earliest missionaries in Scotland, especially in that region. Although there is not enough evidence to confirm this, it is logical that Constantine may have been a disciple or companion of the great St. Kentigern Mungo, who served in Stratchlyde at the same period.

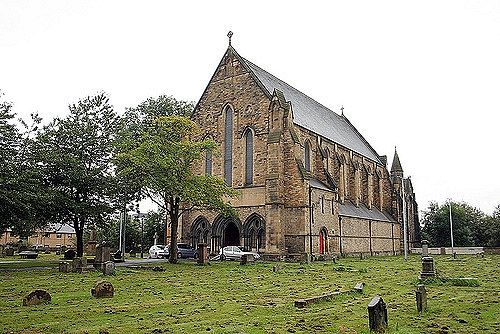

It is supposed that the relics of St. Constantine are inside a glorious, richly carved elaborate sarcophagus at Old Govan Church which stands on the site of his monastery. This church is very ancient, though it was rebuilt in the nineteenth century. In 1855 a beautifully decorated coffin was discovered in the churchyard of this temple that dated approximately from the tenth century and contained human remains. Some historians and hagiographers believe that these are the holy relics of the penitent king, missionary, abbot and martyr Constantine. This coffin with possibly the saint’s relics stands inside Govan Church to this day.

Old Govan Church is unique in many ways (apart from having an Orthodox saint’s relics). Firstly, it has been a permanent place of worship since the sixth century. Secondly, many fifth-century Christian burials were discovered within its churchyard, which is circular—another Celtic feature. Thirdly, over thirty ancient carved Celtic Christian, Pictish and Viking crosses of the ninth to eleventh centuries were found in its graveyard, and now they are housed in the church. Fourthly, one of the former ministers of this church in the 1930s was Reverend George MacLeod (1895-1991). He was a remarkable personality.

A baron who became a soldier, he was struck by the horrors of war, by the social injustices towards common folk and eventually became a minister of this church. Much impressed by its early Christian heritage, coupled with experience of prayer in a Russian Orthodox church, he decided to serve the Lord more completely. Thus, in the 1930s he founded the famous Iona Community on the isle of Iona and restored its abbey church, which had been established by the great St. Columba. Although much driven and inspired by Celtic spirituality, he remained a Presbyterian to the end of his life, but his contribution to the reawakening of the spirit of the early saints in Scotland cannot be overestimated. MacLeod led the Iona Community from 1938 till 1967; the latter still exists and it aims to promote Celtic Christian spiritual life and worship, Christian fellowship, printing activities, and imitating the Celtic saints.

Among the places of special veneration of St. Constantine in Cornwall let us mention the large village with the name Constantine, where a fifteenth-century parish church is dedicated to him and where local residents still honor his memory on March 9 (his feast according to the old calendar); and the village of Constantine Bay, on the Atlantic coast of north Cornwall, which is famous for St. Constantine’s Chapel and holy well. Both villages are named after this holy ruler.

This is what Nick Mayhew Smith writes in his fundamental work, Britain’s Holiest Places, about Constantine Bay:

St. Constantine’s well leaks out of the corner of a stone well-house in the middle of the Constantine Bay golf course. A public footpath leads to the well, which is housed under a shelter, half buried in the grass. The well-house is a tiny room with thick stone walls. It was used for rituals involving the well water since there is a ruined church seventy meters (c. 230 feet) away uphill, hidden amid scrub. It is impossible to enter the building now because of the algae and flowing water. The shelter is open on all sides, with a modern stone wall around it. Inside the well-house are benches on either side. The floor is now wet, but there was once a channel through the middle that contained the flow. The building is twice as long as it is wide, an indication of Celtic origins. It was still used in the eighteenth century by people who would sit and bathe in the stream of water. Nowadays you can run your fingers through the holy source as it emerges at one end of the shelter.

We can add that the healing powers of its water were praised as early as the Norman Conquest. It was even said that praying at this well could bring rain at times of drought! The well was subsequently forgotten and subsided due to the dunes, and unexpectedly rediscovered only in 1911. Now its water is clean again.

For many years, Constantine was the patron saint of the parishes of Dunsterton and Milton Abbot in Devon, and the latter still has a parish Church of St. Constantine that has been traced back to 1155. The area called Welsh Bicknor in the English county of Herefordshire close to the Welsh border has a church in honor of St. Margaret, but the Welsh name of the parish is “Llangystennin Garth Brenni”. The parish church in the Welsh village Llangystennin (“enclosure” or “church of Constantine”) in Conwy is dedicated to St. Constantine, although it is not known whether its patron is St. Constantine of Cornwall or the Holy Emperor Constantine the Great.

Holy fathers Piran and Constantine, pray to God for us!