Priest Roman Vityuk speaks about why residents of Russia’s backwoods pray for the Chinese, whether we should be afraid of China or display a good Christian interest in it, why in the Chinese version of the prayer “Our Father” the word “bread” is replaced with “rice”, and what kind of people we should be in order to have success in our Orthodox mission to China.

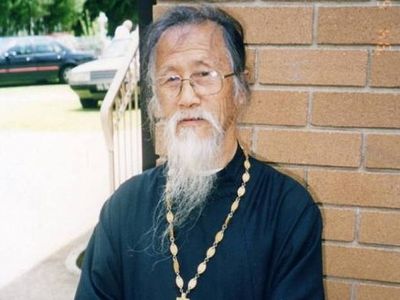

Father Roman lives and serves in a remote area of the Yaroslavl region [in the Central Federal district of Russia with its administrative center in Yaroslavl—250 kilometers/155 miles from Moscow], in the Sutka village of the Reytovo district. One of his hobbies is cross-country skiing and in winter he can run up to twenty miles a day (in summer he covers the same distance on a bike). He is fond of Russian bathss (in Russian: banya) as well. But his greatest hobby is picking up foreign languages. English, German, French, Ancient Greek and Latin are, of course, interesting and necessary, but the priest takes a special interest in the Chinese language and culture. So it is a wide circle of interests. But it is strange enough: Where is the Reytovo district of the Yaroslavl region with its forests, the Rybinsk Reservoir and the former town of Mologa that was engulfed by its waters, and where is China?... However, if you begin to talk with a Russian of long distances, you will only make him laugh.

Pentecost versus Babylon

—Fr. Roman, first of all, please explain us this phenomenon, which is very bizarre for Russia’s backwoods: a priest from a village in the Yaroslavl region is keen on the Chinese language. How did your passion for the Chinese language and culture start? When did you end up studying them?

—My family and I lived in the Transbaikal territory for ten years—from 2003 till 2013. Our middle child went to a language classic school where Chinese is taught from the second grade. So this subject became our family business because nobody is interested in getting a D in Chinese! My wife and I are passionate about languages and she even has an honors degree in foreign languages. So learning languages is our family tradition. And our son graduated from that classic school and was awarded a gold medal long ago. Of course, we are very pleased.

—You speak not only Chinese. You also speak English…

—English is my second language. I am proficient in it and teach it as a private tutor in order to make some money on the side. German was my third language at the institute; French, my fourth language, was taught at the seminary; we also had Ancient Greek and Latin in the curriculum. Picking up languages is so exciting. In my opinion, it is vital to learn and master foreign languages for your pastoral work, for a better understanding of the world and a fuller communication with people. In addition, you understand your native culture and native language more thoroughly if you look at them from outside.

—And what about Church Slavonic?

—Sure! Many details become clearer. Besides, Church Slavonic is not “foreign” for us at all. But, unfortunately, the level of Church Slavonic of many modern Russian Orthodox people leaves much to be desired. It’s the same situation is with other foreign languages. I think it can be said that if we try to master foreign languages, take an interest in the culture and history of other peoples, then, thanks to our zeal and with the help of God, we can overcome the curse of the Tower of Babel, the confusion of languages. It is called cross-cultural communication: a deeper understanding of a foreign culture and its specifics is of practical importance for a Christian mission. In the beginning was the Word (John 1:1), isn’t it so? The Greek “logos” is a broad concept, a real diamond cut with many facets. I believe that learning foreign languages, “philo-logy”—that is, love of logos, helps us a great deal spiritually.

—Through our love for languages we are getting closer to understanding of the first words of the Gospel of John [In the beginning was the Word…], isn’t it so?

—Yes. Each language is like a code intended for comprehending the world. An elementary example: Two different English words—“butter” and “oil” are expressed in Russian by only one word “maslo”. Moreover, the word “oil” can also mean “petroleum” and “kerosene”… To say nothing of Chinese, where so many puzzles and discoveries will await you! And it is interesting to know philosophical and theological terms well, how to grasp and express them rightly.

Weary atheism, worn-out souls

—But if you study one or another language seriously, then your introduction to this people’s culture is inevitable (and necessary, too). How have you personally familiarized yourself with Chinese culture? As I know, you have profound respect for this nation’s culture. So how did you become acquainted with it?

—I first saw many Chinese people at Izmailovo Market in Moscow back in 1998. Earlier in the city of Chita, the Chinese mainly worked in the construction sector. Chita is situated in a frontier region; the Russian-Chinese border is 400 kilometers (c. 248 miles) away from the city. Many local people are used to going there for shopping on weekends. One of our children went to a Chinese school, and we used to go there with him to buy clothes. Just across the border is the city of Manzhouli, which is half as large as Chita and the biggest Chinese land port of entry. It developed with Russian money; originally there had been a station with a few houses in the steppe there.

—As an Orthodox Christian, as a priest I thought to myself many times: “How can I communicate with our neighbors, what can I speak with them about? What can I give these people as a pastor, since we run into each other very often.”

—Can you say that the Chinese are religious people?

—Most of the Chinese are indifferent towards religion. This is like the Stagnation Era in the USSR [the 1970s and 1980s]—there is atheism, but what is this atheism like? A weary atheism, total disappointment, cynicism… But the soul is seeking for something. It seems this is exactly what we experienced in the late eighties.

—But how can we gain their interest? What is really important to them? There is a native Chinese mystical tradition called Taoism. But in practice it boils down to a collection of superstitions and rites with physiological “lifehacks” meant for “maintaining perpetual youth”. There is another religious tradition that is more spiritual—Buddhism. Chinese Buddhism is different from, say, Thai, Vietnamese, Tibetan or Buryat Buddhism, just as Christianity has several different confessions. So Buddhism has absolutely different schools, traditions, and practices. As for mysticism and spirituality, whether it be Buddhist or Taoist, they are not popular among the country’s residents at all. Likewise, if we approach those tipsy “Orthodox” revelers who gather at Russian cemeteries on Pascha and try to talk about the Jesus prayer and hesychasm with them, there will be no effect. Commercialization of the spiritual heritage is also peculiar to China; for example, Shaolin Monastery is a huge business center, a commercial enterprise rather than a spiritual center.

But there is one more native, deep Chinese tradition, which is secular rather than religious. It is Confucianism. It is a set of moral rules as to what kind of hierarchy and duties should be in the state and family. The element of mysticism in the Confucian tradition is ancestor veneration. For secularized Chinese people the veneration of their ancestors is a sacred duty.

Not even in Israel have I found such faith

—Have you met any Chinese people who consciously converted to Christianity? What does Orthodoxy mean for the Chinese?

—In December 1994 I served in Rostov Veliky [a historic picturesque town in the Yaroslavl region] and a Chinese film crew visited us. The movie, called Red Cherry, was on the theme of war and dedicated to an anniversary of the Great Victory of World War II. I well remember how the producer came into our refectory where we had numerous paper and wooden icons. He was delighted with them and said, “I have invited several icons, too.” The Chinese don’t use the verb “to buy” in reference to holy objects—for them the verb “to invite” is appropriate here.

As for the Chinese who became committed Orthodox Christians, I once baptized two women from a Chinese region that borders our Transbaikal territory. One was a professor and deputy of the All-China Congress of People’s Representatives, and the other was her niece, a translator. They chose to be called Tatiana and Valentina in Baptism. I presume “Tatiana” was taken from the novel in verse Eugene Onegin by Alexander Pushkin. Many thanks to Alexander Sergeevich—the word of a poet can lead people to Christ even through centuries! But I never met them again. The state of China is pursuing a prohibition policy towards religion.

—So those words of a Chinese producer first inspired you to study China?

—Yes, they stuck in my memory forever. I also did my military service at the border—in the sector where there were armed conflicts. And then perestroika began with the “thaw in relations”, so details were ordered to salute on meeting each other. There was a curious incident at the frontier post. The deputy commander in charge of policy went a little too far by setting up a stand reading, “Our great neighbor China”. When the head of the political department came he told him to rewrite it as: “The adjoining state of China.”

—And what is sacred for them?

—I have already mentioned ancestor veneration. They also have Qingming Festival, celebrated early in April, the name of which literally means, “a festival of pure light”. It is like Pascha and Radonitsa [remembrance of the dead on Tuesday after Thomas Sunday in the Russian Orthodox Church] taken together. On that day public and family visiting of cemeteries is compulsory: They bring pussy-willow branches and green branches with flowers, and decorate the graves. They also bring food and ritual gifts for the departed. I believe that arousing interest in spiritual things through the afterlife of their forebears, proceeding from this tradition, is a right method of Orthodox missionary work.

—To break through the Chinese Wall? That is quite possible, provided we are Christians

—Do you get the impression that, since we are on the cultural border, we are very different from China in terms of culture, civilization, and history? Our vision of history is quite different and, in my view, geopolitics is not a uniting factor for us. Do you feel that the borderline that lies between us is in fact insurmountable, as was the case with the Berlin Wall? In short, that we are strangers to each other and there is no point in talking about any Christianity in China? Though your example with two Chinese women is a good counterargument… But there were only two of them. Yes, there were also the Holy Martyrs of China [who died in the so-called Boxer Rebellion in 1900]. So how can we begin a dialogue with our neighbors? Isn’t it doomed to failure, since we are very different and even strangers to each other?

—A good, friendly communication with neighbors is always important. If your personality, if the whole of your life is inspired by Christianity, then this candle will not be hidden away; this light will be seen. And if at the outset we just behave like true Christians, they will surely open up to us, seeing our goodwill, our good deeds… The Chinese appreciate it when Europeans can speak their native language with them—they simply begin to thaw.

—Thus, we can even “break through” the Chinese Wall, can’t we? Of course, provided we are Orthodox.

—Certainly. They are sensitive and responsive people and greatly appreciate kindness. At the same time, they are of a reserved disposition; they can bear something negative a long time and be silent. But the Christian seed must be sown, it will undoubtedly yield fruit.

—And does the length of seeds’ germination period matter? Is it early for me to write a report on the triumphal procession of the Christian mission over the large expanses of China? Or can we take our time in spreading the Gospel of Christ and labor for 100, 200 years or more?

—Even 1000 years, if needed. That is absolutely right. We must plant the seeds all the time, and it is God Who ordains the time of germination. China has a very long history, the Chinese are never in a hurry—this is a national characteristic of theirs. We must simply work. That is all.

The Byzantine lesson

—But in what light do the Chinese see us? There is the Manzhouli Frontier Station—Russians have crossed the border and come there in great numbers for years to have fun and do shopping—both businessmen and ordinary residents. Vodka is good there, at half the Russian price. Prices at restaurants and saunas are moderate. And what do the Chinese see from these nominal Orthodox people? Revelry and debauchery—which has not given a good impression of Russian culture. St. Herman of Alaska, who came to Alaska with his Valaam mission, complained about the Russian fur trappers who corrupted the native Aleuts. But the people were Orthodox, baptized, from the real “Northern Thebaid”, that is, the Vologda region. Hence St. Herman’s complains about and disappointment with these Orthodox people…

—But can we follow the Byzantine Empire’s example? After all, for Byzantine Greeks we were like “the Chinese”; moreover we were vicious and aggressive to boot. But the Byzantine Empire gave us its main treasure—Christ. I doubt that it would have done this by military force or through diplomacy, and it was not so strong at that time anyway. But the Byzantine Empire gained its principal victory—it introduced Russians, former barbarians, to the Gospel, taught us to read it and, as can be seen from our Church calendar of saints, even to live it. Can we say that Russia, provided it lives according to the ideals of Holy Rus’, can (and even must) repeat this feat? And if we use the opportunities that the Lord gave us many years ago—to be genuine Christians, then we cannot help but influence the Chinese people (after some centuries, or, maybe, God willing, even in a day)?

—Yes, to my mind the situation is very similar. The Lord is giving us this opportunity and we need to spread His Word. It is the mission of the Apostolic Church to bring the Word of God to the whole world. The Savior said it very clearly: Go ye therefore, and teach all nations (Mt. 28:19). He did not say: “Wait until they yield fruit, until piles of reports are written.” Some peoples accept Christ earlier, some—later, but I don’t think that the exact time matters to God, for One day is with the Lord as a thousand years, and a thousand years as one day (2 Pet. 3:8). We don’t know when the Lord is going to lead the Chinese nation to Himself. Beyond all doubt, He will reward the laborers who came “at the eleventh hour” as well as those who worked from the very beginning… Our duty is to be faithful to Christ. We are continuing the apostolic mission, witnessing to Jesus, and sowing the seed. And impatiently waiting for a result may ruin all the work. And, most importantly, if we are not good Christians ourselves, then it would be strange to demand that others grow spiritually as soon as possible.

China is a delicate matter

—There is much talk about “the wild Chinese business world”, wealth… They say the wealth of many Chinese businessmen was gained wrongfully. Am I right in my understanding that in the Chinese tradition the word “richness” is not always written with a capital R, that they have disdain for it? Or, on the contrary, they crave for wealth?

—The Chinese use hieroglyphs, not letters… As for their attitude towards riches, I wouldn’t say that the Chinese are exclusively hard working, that they are ready to drudge “for peanuts” in order to survive (for some reason such an opinion of them is widespread here). Usually, when somebody reaches the top of a social pyramid, he will compensate for all his past humiliations. Still, China is home to over one billion people and the situation is much tighter there than in Russia. Most of village residents live in abject poverty, while some cities, especially in the south, are enjoying a luxurious life. The social stratification is strong.

—So, saying that China is walking fast into a brighter future is far from reality?

—Many “social landmines” have been “laid” there. The one-child policy has created a disparity: there are very many old people and too few young workers. Now the one-child limit has been lifted. They have started with northern regions in order to put pressure on the border… As for Russia’s Far East, its population density is very low.

—Is it easy to find common ground with the Chinese?

—Hmm… Just to exchange several common phrases—no problem. Etiquette is highly valued there. Composure and courtesy are significant in any situation. Yet the morals in China are different from ours. In many cases what we regard as a sin is valor and intellectual superiority for them. For example, to fraudulently become the gainer in a bargain. It is not a sin for them. Even a written contract doesn’t necessarily signify. Those who regularly purchase products from AliExpress will understand what I am speaking about.

“Our Chinese”

—We know about the Chinese Martyrs in Manchuria…

—Yes, these are the children of the Russian Orthodox Church, martyred during the infamous “Boxer Rebellion”, when all that was alien and detrimental for China (in its organizers’ view) was being destroyed. It was followed by other persecutions. During the so-called “cultural revolution” they tried to eliminate everything without exception; only a few priests and bishops survived (now they are dead). There are a handful of parishioners today; the number of converts is greater.

—Manchuria has an area whose name means “Three Rivers’ Region,” which lies along the east border of the Transbaikal territory. After the Revolution many Cossacks came to live there; so there is even a Russian autonomous district there making the Russian people one of the official national minorities of the People’s Republic of China.

—That means that Russians live there, right?

—Yes, they do. Though they look like Chinese. They built a Church in honor of St. Innocent of Irkutsk in the town of Labdarin (in front of the Russian town of Priargunsk) in 1999. Then they were not able to consecrate it for ten years as they couldn’t obtain a permit. In 2009 Metropolitan Hilarion came and finally consecrated it, and formally an old frail Chinese priest (who was supported by his assistants as he walked) served there. Now all that they do is gather for Sunday prayers, but they have no priest to celebrate services. They bear Russian names which are written in hieroglyphs, for example: “nadasha” for “Natasha” and “damala” for “Tamara”.

—Therefore, judging by your words, as you may notice, there is an acute need for an active Orthodox mission there?

—Yes. By the boldest estimates, the People’s Republic of China is home to about 200 million Christians, mainly members of Protestant denominations, plus two Catholic groups (one legal and pro-government, another illegal and in communion with the Vatican). Meanwhile the ———Christian West is losing its heritage. We simply cannot turn a blind eye to this spiritual hunger. A project of large-scale mission is needed.

Our daily “fan”

—Now to a happier theme: the Chinese language that you are learning. Are there any interesting moments from the missionary point of view there? The four tones in this language might be of interest to choir directors. But what about specific points in its vocabulary?

—The same syllable pronounced with different tones is the same for our ear. But for the Chinese these are different sounds. We cannot understand it…

—Their names chiefly consist of three syllables: first a surname of one syllable and then a personal name of two syllables. For example: “Mao” is the surname and “Zedong” is the name. They don’t encourage choosing names according to the Church calendar. Imagination is needed here, a name is expected to be original and beautiful.

—What about “Isaac” meaning “laughter”? What about all our “the rock”, “seagulls”, “gifts of God”, those “of the sea”, “the fourth” and so on?1

—Of course, you can translate something, but a canonical Christian name in transliteration fits only for communication with Europeans, “it is not serious and proper” for the Chinese. The Chinese also have children’s names, used until a certain age. But giving names on the eighth day after birth, as we do… This tradition is alien to them.

—In other words, such given names as “St. Nicholas’s Unmercinariness”, “The Heights by Humility”, or “Riches by Poverty” would be normal?

—It is a fine idea! I will tell it to the Chinese who may want to be baptized.

—Is it true that when the prayer, “Our Father,” was being translated into Chinese the word “bread” was replaced with “rice”?

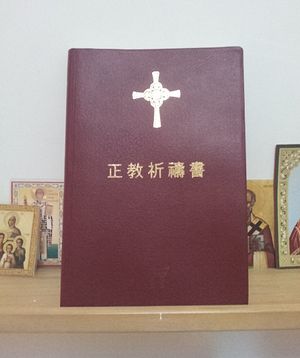

—In Chinese the verb “to eat” usually consists of two characters, meaning “to eat rice”—“chi fan”. True, rice is a major food in China. And they have two graphic symbols for “rice”: uncooked rice 米 (“mi”) and cooked rice 饭 (“fan”). In the Lord’s Prayer and the sixth chapter of the Gospel of John (where “the Bread of life” is mentioned) the Chinese usually use the hieroglyph with “rice” as the key element—粮.

—It means that the prayer reads “…give us this day our daily rice” for missionary purposes?

—Yes, we can say that it is “grain” or “meal” in general, but what is meant here is “rice”, not white bread.

It is naturally very easy for modern people to understand the archaic system of the Chinese written language. If you make whole phrases of smiley face emoticons while texting, then my congratulations to you—you are using hieroglyphs. Knowing the main meanings of hieroglyphs, you will be able to understand the meaning of a text. It is very clear to children that a hieroglyph is a sort of smiley, and smileys are a fascinating game!

Not Mordor, but an excellent opportunity for preaching

—I cannot help but marvel: we are sitting in a remote area of Russia’s Yaroslavl region and talking about an Orthodox mission to China! Doesn’t it seem a bit weird and crazy to you? How can one help to bring Orthodoxy to China (apart from prayers, of course; although I realize that prayers are also vital)?

—There are the words in the book, The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky: “Show a Russian schoolboy a map of the stars, which he knows nothing about, and he will give you back the map next day with corrections on it.”2 So interest (as well as prayers) is understandable and well-grounded here. More than that, today distances and speeds are different from those of old times. And one more thing: Why not be interested in China and wish the eternal salvation to its residents?

—If you ever have a chance, will you return to China one day?

—Definitely! We have included it in our family plans. Frankly speaking, I don’t especially like the cities like Beijing—a huge, depressing megalopolis with smog and infinitely repetitive standard elements of spatial layout. Meanwhile, there is a wealth of historic sites, ancient capitals, like Xi’an with the “Terracotta Army” sculptures, or picturesque places like the Guilin Mountains where the movie Avatar was shot. Beyond all doubt, the most “Russian” sites are Dalian and Port Arthur [now called Lushun], which was formerly closed. And, of course, Harbin—the capital of the Chinese Eastern Railway. By the way, Harbin still produces kvass [a traditional Russian fermented non-alcoholic drink, made from rye flour or bread with malt] using an authentic Russian recipe. Such is our “petty patriotism” (“kvass patriotism” in Russian) with Chinese specifics! There is a book, entitled The Long Road, by the Russian singer, poet and actor Alexander Vertinsky, which can be strongly recommended to all readers who are interested in the Russian China.

—So you earnestly recommend that everybody not regard China as Mordor [the “Black Land”, or the “Land of Shades” in the fiction world of J. R. R. Tolkien] and something awful. On the contrary, it would be wiser to take an example from the good old Byzantine Empire, which enlightened its neighbors centuries ago, even though they were “strangers” to it. And we shouldn’t forget that we were entrusted with the task of spreading the Gospel, if we are Christians not only in name.

—There are many things in China that you will find incomprehensible, bizarre, and unacceptable, but Chinese people are very friendly to Russian people, and I know this from personal experience. There is a very rich Russian Orthodox heritage, and real prospects for preaching Christ in China.