I remember how Fr. Paul, the father-confessor of Mt. Sinai rejoiced at seeing the mottled carpet of fields and green forests of Russia. To understand his joy one has to live for a time in the desert—water, flowers, and the singing of birds gain a new appreciation there. Sometimes the waterless desert becomes life, and then a meeting with such a man as the abbot of the Monastery of St. Gerasimos of the Jordan, who created an oasis in the middle of the Jordan desert in both the literal and figurative sense, brings you new strength for life and love. “Indescribable feeling! May God grant that all Christians be vouchsafed to spend some time here and that the Lord would strengthen the monks who defend “Thermopylae”i; “It is good everywhere in the Holy Land, but here the soul opens up”; “Fr. Chrysostomos is always in the fore; he is a very kind father, if not to say a saint.” These are the impressions of Greek pilgrims, resonant with our own experience of the monastery of St. Gerasimos of the Jordan and its faithful guardian, Archimandrite Chrysostomos (Tavoulareas).

Archimandrite Chrysostomos (Tavoulareas)

Archimandrite Chrysostomos (Tavoulareas)

“You are journalists from Russia?” the Greek gatekeeper asks us with curiosity. You need to meet our abbot. He is an extraordinary man!” Having venerated the holy shrines, we went outside the walls and there, in the arkhandariki [guest refectory], under the open sky, we listened to the stories of Archimandrite Chrysostomos. His simplicity and love break down all communication barriers in a moment, and our hearts are opened in response to the kindness that pours from him.

Archimandrite Chrysostomos (Tavoulareas) has spent forty of his sixty years here in the Holy Land. He loves people regardless of their faith and biography. He loves birds, animals, plants, and all of God’s creation. He loves his homeland. Even the ringtone on his mobile phone, which rang numerous times during our conversation, is the Greek national anthem,ii “Χαίρε, ω χαίρε, Ελευθεριά”. The abbot sincerely feels that, “We Greeks should be proud that we were born Greek and should strive to preserve the traditions of our homeland.”

“From thy youth thou didst love Christ”

—I am unlearned, from a village near Sparta in the Peloponnese. I became a monk at an early age. When I was eleven years old I left for the zealot,iii old-calendar, strict monastery of Panagoulaki in Kalamata. I was not allowed to finish high school. The abbot said, “You already know how to read the Psalter, the Octoechos, and that is enough!” My parents divorced then and I lived with my mother (my father was a man of somewhat unruly morals), and my family was very poor.

—How did your mother accept your leaving for a monastery?” After all, you were her only son…

—My mother was a saintly woman. She always carried a prayer rope, wore a headscarf, and was entirely immersed in prayer. She continually abided in a state of emotional equilibrium, and related to all people with dignity.

So, at age eleven I left for the monastery of Panagoulaki. There were ascetics living there—people of lofty spiritual life. When in 1924 Greece changed to the new calendar, this monastery remained on the old calendar.iv There labored Fathers Joel (Yanakopoulos, 1901–1966), a researcher and commentator on the books of Holy Scripture; Agathangelos (Vourdoulas), Chrysostomos (Papasarantopoulos, 1903–1972), an outstanding enlightener of Africa in the twentieth century; and Joachim (Yannanitis).

Saint Philoumen at Jacob's Well.

Saint Philoumen at Jacob's Well.

—How did you end up in the Holy Land?

—At age twenty I joined the army. There I met Archimandrite Palladios, the Exarch of the Jerusalem Patriarchate in Greece. He served in one ancient little church in Plaka, just above the metropolia, beneath the Acropolis. I, a soldier, would go to the city on Sundays. I liked the ancient, quiet churches. I would go there and sing (although I don’t know music, I can sing). Once Fr. Palladios asked me, “Where did you learn to sing, soldier?” I said, “I am a monk. I live with the zealots in the monastery of Panagoulaki.” He was surprised, “With the zealots?” “Yes.” Then he asked, “Do you want to go to Jerusalem?” “But how? I have no money! And the abbot won’t give me a blessing to go to Jerusalem.” “Well, alright,” he replied, “you think about it, and if you decide to, then come.”

Right after I finished my service in the army I spent a month and a half in the penalty battalion. When I returned to the monastery, Abbot Christopher asked me why I was late. “Show me your release papers,” he said. There he saw the notation about the penalty battalion. “Five hundred full prostrations! Bread and water for forty days!” Do you know what my great sin was?! It was written in the release papers in “Katharevousa”viii (they used to write in Katharevousa then): “Taken smoking in the barracks.” A real universal deluge broke out upon me. “Three years without Communion! 500 prostrations!...” The abbot was an old man, very aged! He lived a saintly life! I said, “That’s it, I am leaving.” He said, “No! Don’t do anything, only stay!” But I had already made up my mind; I went to Athens and looked for Fr. Palladios. He bought me a ticket and gave me 1,000 drachmas for the road. I flew into Ben Gurion [airport]. and who do you think met me at the airport? Metropolitan Basilios himself. He took me to Bethlehem.

So, I have been a priest in the Holy Land for forty years now.

—What is the most important thing for you in faith and life?

—Love. We all have sins (the devil doesn’t sleep!), but we should always have repentance and ask God for forgiveness. We should have love and humility in our hearts.

“May this monastery become an oasis in the desert!”

At that time I served as a deacon in Bethlehem and I got into a tussle with the Catholics. The Jerusalem Patriarchy decided to punish me and send me for a time to the monastery of St. Savva the Sanctified. But one elder, Geronda Theodosios, an abbot from Asia Minor, suggested to the 92-year-old Patriarch Benedict to send me to the monastery of St. Gerasimos of the Jordan, which was abandoned and located on rather dangerous territory. No one ever went there voluntarily. So, I and the Patriarch’s deacon set out to have a look at the place; we travelled there over a dusty road in 50 degree (Celsius) heat. We reached the monastery, and regardless of the fact there wasn’t a single green leaf in the vicinity, I understood immediately that I wanted to stay there! This place immediately took root in the depths of my heart!

The flags of Greece and of the Guardians of the Holy Sepulchre, hanging above the monastery entrance.

The flags of Greece and of the Guardians of the Holy Sepulchre, hanging above the monastery entrance.

—“Very Good, then go; stay for a year or two and when you return we will find you a better spot to be abbot.” I answered, “Your Beatitude! Can I ask you for mercy?!” “What?” (He thought that I meant a shorter period.) “If only it is possible, bless that this be the place of my whole life.” “Your whole life?” “Yes!”

He arose, made the sign of the cross over me—not as a priest but as a patriarch, with both hands, saying, “God bless you! And may the Monastery of St. Gerasimos of the Jordan become an oasis in the desert.”

The monastery

And the desert places of Jordan shall blossom and rejoice... (Is. 35:2)

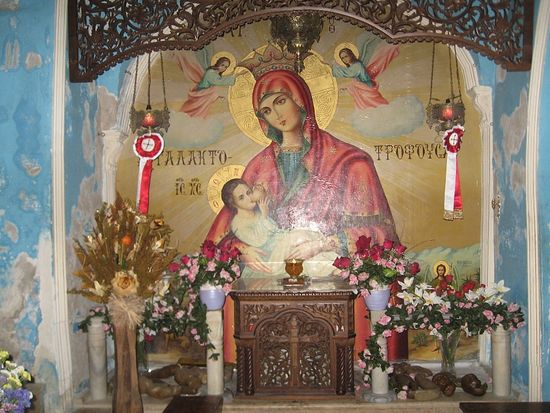

Icon of the Mother of God

Icon of the Mother of God

The monastery of St. Gerasimos of the Jordan is located in the Jordan desert on the road to Jericho, not far from the very place on the Jordan River where Christ was baptized. Just below the monastery on the hills of sand there are caves still intact, where, according to tradition, lived St. Mary of Egypt and St. Photini. On the site of the monastery itself, St. Joseph and the Mother of God, with the Infant Christ, stopped to spend the night on their way to Egypt.

The monastery founded in 455 by St. Gerasimos is one of the most ancient in Palestine, and was distinguished by its austerity. The brothers would remain five days in their cells, eating nothing but bread, water, and dates. On Saturday and Sunday they gathered, and after receiving Holy Communion they would share a meal and eat cooked food with a little wine.

The monastery courtyard.

The monastery courtyard.

Oasis in the desert - a view of the Monastery of Saint Gerasimos of Jordan.

Oasis in the desert - a view of the Monastery of Saint Gerasimos of Jordan.

However, the first five years I lived completely alone (without water, electricity, telephones or roads). I literally had nothing to eat. I begged alms of tourist buses to somehow sustain the monastery. I made candles myself. The only water was rainwater. Later I found a spring.

The discovery of a spring

Saint Gerasimos of Jordan.

Saint Gerasimos of Jordan.

We worked using traditional methods. We dug with a mattock and pickaxe, and to go down further, we cleared it with a shovel. At that moment the two workers below dug while I emptied the buckets above. Suddenly they began to shout, “Abouna,ix come down, we’ve hit pebbles.” They had reached rocky ground. I jumped down. I lowered myself down, grabbed the pickaxe, and set to digging. I dug and dug; I went down another half meter and noticed that the pebbles were becoming more and more damp. In 1.5 meters we hit water.

I see in this a miracle of St. Gerasimos. If I had not prayed to him and we had stopped working, I would have closed the well the next day (we were acting illegally; it is against the law here to uncover a water source or do construction work without special approval.) It is also a great miracle of the saint that the water turned out to be pure and sweet. Usually in this region close to the Dead Sea the water is not just salty, it is very salty; it contains sulphur and smells like rotten eggs.

Traces of Thessaloniki in the Jordan Desert

—In the monastery there is a tower that reminds one of the White Tower in Thessaloniki.x Earlier, when there was no access road to the monastery, I would walk to the road that led to the Dead Sea. Groups from Greece headed for Sinai would pass along that road.

The Tower of the Monastery of Saint Gerasimos of Jordan.

The Tower of the Monastery of Saint Gerasimos of Jordan.

Later, whenever groups came from Thessaloniki they always brought me something. That is how part of my soul was left in Thessaloniki.

The cells here are always open

To the right, you can get some bean soup.

To the right, you can get some bean soup.

I am the only priest. Soon the deacon Kyriakos will be made a priest. What worries me is the future. The young people are not entering monasteries, and there is a huge need for successors to come and take our places in time; to labor here in asceticism and preserve these holy places.

The monastery buzzes with work all day

—We rise at 5:30 a.m. and take breakfast together. Then each goes and does the task appointed to him: one makes the meals, others go to work the land or tend the animals. From early morning the candle-making, icon, and mosaic workshops are active. We have adorned the entire church with mosaics. We use only natural stones of around forty-five different colors.

The Arabs do all the construction work. Arabs also work in the candle-making and mosaic workshops. They all say, “We are working not as hired workers, but as the children of Fr. Chrysostomos.” Even the Muslim Arabs rise to pray with bended knee at the sound of the monastery bells; the father abbot has embraced them with his love. “My name is Khaleb,” one of the workers relates, “I have been around Fr. Chrysostomos from my childhood years. Abouna is a very good person. We work as best we can, and he treats us like his own children.”

Fr. Chrysostomos helps the local children, whom he loves very much. “There is great poverty in this region,” he says, “and it makes no difference to us whether a person is Christian or Muslim. God is the same for all. There is no division in love.”

—In the monastery there are camels, goats, horses, rabbits, partridges, chickens, and ducks. When the camels are a year old we teach them to carry people (after that it’s too late). It is not expensive at all to ride a horse or camel, and this gives us the opportunity to do something for the monastery! We have local donkeys here, and a “cypriot”. Cypriot donkeys are tall and hardy, and we use them in Hebron. But if the local ones cost 25 euros, the ones from Cyprus cost one or two thousand. Our goats—from Damascus—local ones that the Bedouins have, are too small (after all, nothing grows here!). I need 500-600 euros every month to feed these animals.

The doors to the monks’ cell in the monastery of St. Gerasimos of the Jordan have always been open, for someone might pass by who needs help. The fathers do not say, “hospitality”; the fathers say, “love”. And what is love in the desert? To offer a little water (it is very valuable here!), dates, a bowl of pottage... No matter who comes by, you meet and treat them all!

We are continually preparing food; travel-weary pilgrims come all day. Sometimes there are many, other times few. But there is always a bowl of food for each of them. We have fixed up the pilgrims’ guesthouse (but don’t suppose that it is particularly luxurious—it has only the bare necessities!) The only thing you won’t find in our monastery is loneliness, anxiety, or insecurity.

Do good deeds

The people who come to help Fr. Chrysostomos are those who have been touched by his love. Eustacios Asimakis from Athens relates, “I first came here as a pilgrim in 1998, in a very difficult situation. I saw the works of our Geronda and decided to return and work a while. I asked him about the possibility. “Whenever you want and for however long you want!” Soon I came for four months; I watered the fruit trees and flowers, and carried other obediences needed by the monastery.”

Calliope Pistophidou also crossed the monastery threshold for the first time three or four years ago. “Geronda amazed me by his love and relationship to people. I saw his ascetic labors in the desert, where he has built a little oasis, like a paradise, and I returned to live here. My obedience is usually in the kitchen.”

Fr. Kyriakos, who heads the artists’ workshop, was led here from Cyprus by St. Gerasimos himself. “Before I became a monk I led a worldly life just like all young people. A friend told me about a miracle of St. Gerasimos. I said, “I want to know who this saint is who works such miracles!”

Procession with the icon of St. Gerasimos of Jordan.

Procession with the icon of St. Gerasimos of Jordan.

“Divine grace is like a magnet that attracts metal. It is something that leads you. You have to experience this to understand it. For twenty-two years I lived in darkness. My mother asked me to “Go to confession.” I refused. I did not believe in heaven or hell. But my mother was right—from the day I gave confession my life changed. God’s grace worked in me!

Father Chrysostom and the fawn named Cook.

Father Chrysostom and the fawn named Cook.

To be continued.