Source: My Statesman

December 4, 2015

Justin Marler’s spiritual path moves with the motion of a mandala, sweeping through a series of elaborate and oddly beautiful curves, spiraling back upon itself.

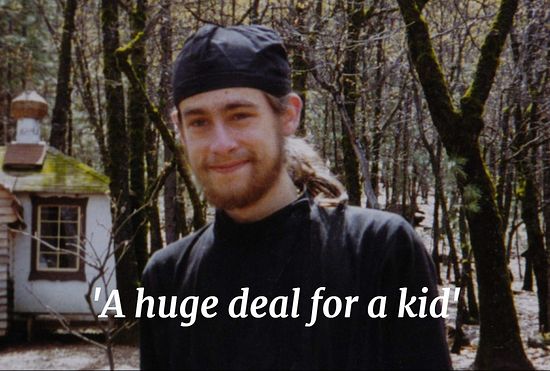

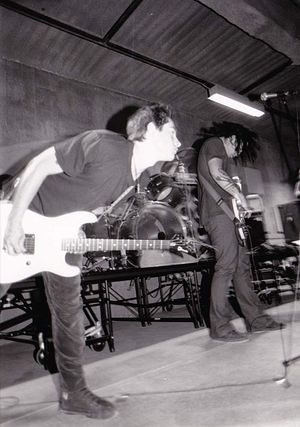

Justin Marler plays guitar in the band Sleep in 1991, shortly before he quit the band to join an Eastern Orthodox monastery. (Courtesy of Justin Marler)

Justin Marler plays guitar in the band Sleep in 1991, shortly before he quit the band to join an Eastern Orthodox monastery. (Courtesy of Justin Marler)

Now, 43, and with the blessing of his church, St. Elias Orthodox in downtown Austin, Marler has recorded an album of punk rock versions of gospel songs called “Hymns for the Apocalypse.” All sales from the self-financed CD — available on iTunes, at Waterloo Records and through his own website — will go to the Hauran Connection, a project that benefits his parish’s sister diocese, Bosra-Hauran in Southern Syria, which has been devastated by civil war over the past four years.

While his former band Sleep almost sold out ACL Live last year, Marler has spent seven years living an ascetic life. (Courtesy of Justin Marler)

While his former band Sleep almost sold out ACL Live last year, Marler has spent seven years living an ascetic life. (Courtesy of Justin Marler)

“The news is saturated with all this information about Syria, refugees, war, all this stuff. To have it be one handshake away, it was no longer abstract,” he says. “It was people in my own parish (who) have family members who are fleeing for their lives or who have been murdered.”

St. Elias was built in the 1930s by Syrian and Lebanese immigrants to Central Texas, but these days it houses a diverse congregation, including families from Eastern Europe and Africa, as well as Western converts like Marler. As part of the Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese, the church traces its history to the ancient Greco-Roman city Antioch on the Orontes, where the apostles Peter and Paul founded the first Christian church. The ruins of Antioch lie near the border between modern Syria and Turkey.

“We have very deep roots there,” says the Rev. David Barr, archpriest of St. Elias. “Many of our parishioners come from the Middle East. It’s a tough time. … I think there’s a great fear of ISIS and that whole movement.”

His congregation includes Iraqi families who fled the violence. “They had family members in Iraq that were killed for no other reason than being a Christian,” he says, “and they were actually trying to get out of Iraq and were found.”

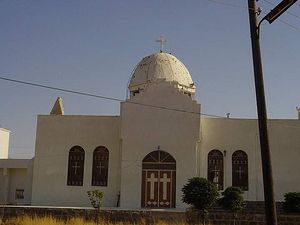

The St. George Church in Jbeh, part of the Bosra-Hauran diocese in Southern Syria. (Courtesy of antiochian.org)

The St. George Church in Jbeh, part of the Bosra-Hauran diocese in Southern Syria. (Courtesy of antiochian.org)

“It’s a very ancient Christian area, but the Christians have lived peacefully with others there for centuries,” Barr says. “They see themselves as a part of the land.”

When the civil war started and warring forces began seizing territory in the region, church construction halted. Four of the parishes have been abandoned. Some of the churches may be destroyed, but Barr says information is spotty and hard to confirm.

The front entrance to a medical clinic in Sweida that is supported by the Bosra-Hauran diocese. The church provides services to anyone in the region regardless of religion. (Handout photo)

The front entrance to a medical clinic in Sweida that is supported by the Bosra-Hauran diocese. The church provides services to anyone in the region regardless of religion. (Handout photo)

In the churches that are still open, many parishioners have fled. Four parishes are more than half empty. The congregants who remain are usually “those who are elderly and cannot flee,” says James Kallail, a deacon and the program coordinator for the Wichita diocese.

“Many have been killed, although numbers are hard to document,” he says. “Two Orthodox bishops from Aleppo were kidnapped about three years ago with no word of their whereabouts or condition.”

The parishes that remain open have been transformed into relief stations, distributing food, medicine and supplies to anyone in the region regardless of religion; money from the sales of Marler’s music will go to those relief efforts.

“Discrimination against Christians has intensified with the war. Suffering, though, has no boundaries and the Church struggles to help all she can,” Kallail says.

“The people there are heroically trying to disseminate food, clothes, shelter to all people there, not just their parishioners but everybody,” Marler says. “And that is really something that I couldn’t not try to help out.”

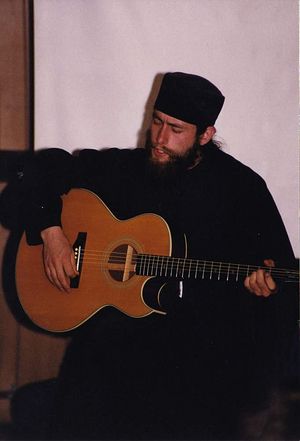

Marler plays guitar at an Eastern Orthodox monastery on a remote island in Alaska in 1996. The monastery was a satellite location of St. Herman Monastery in Platina, Calif., where Marler began his monastic training. (Courtesy of Justin Marler)

Marler plays guitar at an Eastern Orthodox monastery on a remote island in Alaska in 1996. The monastery was a satellite location of St. Herman Monastery in Platina, Calif., where Marler began his monastic training. (Courtesy of Justin Marler)

He toured with the band and recorded the debut release “Volume One.” The band wore darkness on their album sleeve: Tracks included “Numb,” “Stillborn,” “The Suffering” and “Anguish.”

Marler was a straight-edge punk and lived a clean life with no alcohol, drugs or meat. The heaviness of the music and the rampant nihilism in the scene wore on him. Less than half a year into living a life he once dreamed of, he broke down. “I was cutting myself with razor blades and having some pretty significant depression issues and it was leading into, I think, mental illness really,” he says. “I would walk the streets of Oakland and I would be slobbering on myself and screaming. I was just losing my mind.”

Marler reaches out to touch the robe of the Rev. David Barr as he walks past during services at St. Elias Orthodox in Austin. (Rodolfo Gonzalez/American-Statesman)

Marler reaches out to touch the robe of the Rev. David Barr as he walks past during services at St. Elias Orthodox in Austin. (Rodolfo Gonzalez/American-Statesman)

On a whim he flew to Israel on a wayward search for Jesus. After a month of “living in bushes and … kind of homeless walking around,” his grandmother flew him back to California. One day he walked into an Eastern Orthodox bookstore and an encounter with a nun changed his life.

“I challenged her on philosophy and faith and religion and all this stuff and she was so smart and so loving,” he says. “She opened my eyes.”

Marler was “thoroughly amazed” by the world of Eastern Christianity with its emphasis on history and the faith of the apostles. He visited a nearby monastery that housed relics from the age of Saint John the Baptist. “The connection is so ancient and authentic and it drew me in,” he says.

He didn’t leave for seven years.

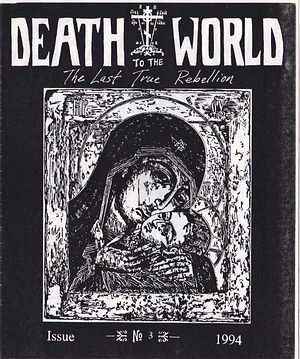

A copy of 'Death to the World,' the 'zine Marler distributed in Bay Area punk clubs while living at an Eastern Orthodox monastery. (Courtesy of Justin Marler)

A copy of 'Death to the World,' the 'zine Marler distributed in Bay Area punk clubs while living at an Eastern Orthodox monastery. (Courtesy of Justin Marler)

Circling back into his D.I.Y. punk roots, Marler decided to start a ‘zine. For a year, he and another monk published a handmade magazine called “Death to the World: The Last True Rebellion.” The handmade zines were illustrated with gothic Christian art and included tales of religious martyrs and stories of salvation. He handed them out at punk shows, wearing his monastic robes. “It was so frightening. It was really difficult,” he says. “I lost a lot of friends because I was a punk who did the opposite of what a punk should do, which is embrace organized religion.”

At the same time, he felt a strong connection between the monastic life and the punk rock ethos of his younger days. “We were sleeping on boards. We didn’t care about how we looked. We didn’t care what the world thought. We didn’t care about fashion,” he says. “And I found that to be so truly punk rock, to rebel against everything that the world has built up as a facade and totally reject it out of love.”

At 26, after four years at the monastery’s satellite location on a deserted island in Alaska, Marler decided it was time to apply what he had experienced and learned in a life in the world.

Marler speaks with Barr after kissing the cross during the dismissal of services. (Rodolfo Gonzalez/American-Statesman)

Marler speaks with Barr after kissing the cross during the dismissal of services. (Rodolfo Gonzalez/American-Statesman)

Marler's blended family includes four children living in far South Austin and one adult child in California. (Rodolfo Gonzalez/American-Statesman)

Marler's blended family includes four children living in far South Austin and one adult child in California. (Rodolfo Gonzalez/American-Statesman)

“I had a moment when I was bawling my eyes out upstairs with my baby and I had a choice to walk through this … not accept God’s will, but actually embrace it as what is necessary,” he says. “I chose that as opposed to completely give up and become an alcoholic… go crazy … I really, really walked into God’s arms and he was there for me. He really was.”

In 2005, he met his second wife, a native Austinite. They relocated to her hometown to make a fresh start. In the monastery, Marler did a lot of construction and he turned those skills to the lucrative business of home renovation and flipping houses. But his wife battled depression and mental illness. “We struggled with that for the duration of the marriage and eventually it just unraveled everything,” he says. They separated in 2011 and divorced the next year.

His life stabilized a few years ago when he reunited with an old high school friend and they married in 2013. His wife, Nova Marler, shares his history in the punk scene and strong Christian faith. Their blended family includes four children living in far South Austin and one adult child in California. “I feel really, really blessed after everything we’ve been through to have an awesome wife and (five) healthy kids who are really good and well-adjusted,” Marler says. “(I) have everything I need.”

Rev. Barr finds Marler’s unorthodox Orthodox Christian journey fascinating. “When he was in the monastery they used a lot of music to reach out to people who were maybe being forgotten … not the typical people that churches go after … the street people, the counter culture.”

Over the years, Marler’s mission has evolved, but the spiritual circle is unbroken. Justin and Nova Marler recently converted a room in their airy Circle C home to house a refugee family. They are willing to sponsor the family’s travel financially and have explored the possibilities with local refugee organizations, the church and connections in Greece.

“Logistically I think this won’t work out, especially in light of the governor trying to close the door,” Justin Marler says. “So we’re looking into providing the room to a local homeless family.”