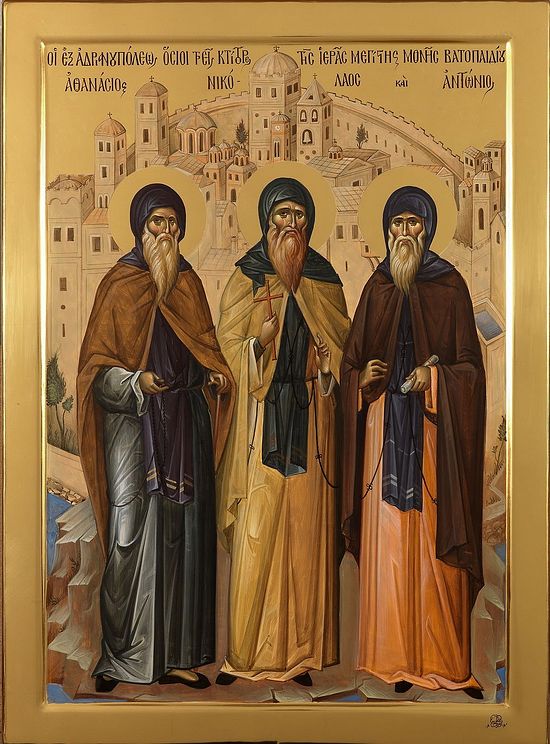

Contemporary icon of Sts. Athanasios, Nicholas and Anthony the Venerable Founders of Vatopedi Monastery, painted by Fathers of Vatopedi

Contemporary icon of Sts. Athanasios, Nicholas and Anthony the Venerable Founders of Vatopedi Monastery, painted by Fathers of Vatopedi

December 17/30 the holy Orthodox Church commemorates Sts. Athanasius, Nicholas, and Anthony, the tenth century founders of Vatopaidi Monastery, one of the twenty great monasteries on the holy mountain of Athos. As with all of the monasteries on the mountain it has a deep and rich history, with a number of saints, and today it houses several miraculous icon and relics.

The Vatopaidi Monastery is regarded as the largest group of buildings in area and volume on Mount Athos. For this reason, from the very earliest years of its existence it has borne the title of the Megiste (’very great’) Monastery of Vatopaidi. In documents of the 11th century it is encountered as the ‘Lavra of Vatopaidi’ and in others of the 14th century as ‘the Great Monastery of Vatopaidi’. Today the monastery is home to the largest brotherhood amongst the twenty ruling monasteries with well over a hundred monks.

Archimandrite Efrem, enthroned as abbot of the monastery in 1990, writes:

Scholars regard the holy and glorious great Monastery of Vatopaidi as one of the finest masterpieces of Byzantium in the world in terms of its superb architecture, which blends into a geographical setting of the greatest beauty. Seen in relation to the deeply-rooted tradition of its thousand years and more of life, it is generally admitted by experts and scholars to constitute a face of the triptych of that race in which that culture was continued and concentrated in the post-Byzantine period—a culture which has already perfected the Parthenon, the expression of the essence of ancient Greece, and Aghia Sophia—the Church of Holy Wisdom—the center of Byzantium’s greatness.

Below is an overview of the history, layout, and treasures of Vatopaidi Monastery, adadpted from information found at A pilgrim’s guide to the Great and Holy Monastery of Vatopaidi

The History

The great and holy Monastery of Vatopaidi stands on a picturesque stretch of coastline on the gulf of the same name and almost in the center of the north-eastern side of the Athos peninsula, five minutes from the sea.

According to Athonite tradition, the monastery was built by the Emperor Constantine the Great (324-337), was subsequently destroyed by Julian the Apostate (361-363) and was re-founded by the Emperor Theodosius the Great (379-395) as a thank-offering to the Blessed Virgin for saving his son Arcadius from certain death by drowning when, as a child, he was in peril in a rough sea near Mount Athos. Arcadius was carried in a miraculous manner to the shore, where the sailors found him sleeping near a bramble bush. For this reason the monastery was called Vatopaidi: from fiaioq and naidiov (= a child).

The same tradition then takes us to the 10th century, when Arab pirates looted and burnt down the monastery, slaughtering the monks and taking away with them to Crete as a prisoner the sacristan, the deacon-monk Sabbas.

The biographer of St. Athanasius the Athonite (second half of the 10th century) mentions three nobles from Adrianople, Athanasius, Nicholas and Antonius, who have a direct link with Vatopaidi. These came to Athos, bringing with them their fortunes, which amounted to 9,000 gold pieces, with the intention of founding a monastery. St. Athanasius, knowing that the monastery of Vatopaidi was in ruins as a result of the incursion of the pirates, sent them there to restore it. In fact, in a document dated 985 we encounter the signature of the monk Nicholas as abbot of the monastery. This is the oldest official written evidence of its existence.

The subsequent growth of the monastery was rapid: in the Typikon of Monomachus (1045), it took second place in the hierarchy of all the monasteries of the Holy Mountain, a position which it has retained until the present. It also gained the right to take part in the Synaxis in Karyes in the person of its abbot and four delegates, to keep a yoke of oxen to ensure bread supplies and to have a boat for its needs.

At the end of the 12th century, the former prince of Serbia Symeon Nemanja and his son Sabbas, subsequently the first Archbishop and Ethnarch of Serbia, were monks of Vatopaidi. The presence of these two saints lent great prestige to the monastery, and to Athos as a whole. St. Sabbas took part in official missions to Constantinople in order to settle issues concerning the Holy Mountain. It was on his request that the monastery ceded to the Serbian saints the apiary of Chelandari, so that they could build the Serbian monastery of that name. Their presence at Vatopaidi and their benefactions to it were always to remain in the memory of the Serbian people, and all the Serbian princes served as protectors and benefactors of the monastery.

It was in the time of St. Sabbas that the monastery flourished as never before or after. It had as many as 800 monks, extended its buildings, thanks to the efforts of the two saints, and founded five new chapels on the site. With the founding of the Chelandari (or ‘Chilandari’) Monastery, a kind of spiritual affinity between the two brotherhoods developed. This has meant that the custom has survived down to the present for the representatives of Chilandari to play a prominent role at the Feast of the Vatopaidi Monastery (25 March) and those of Vatopaidi at that of Chilandari (21 November).

After the unsuccessful attempt of the Emperor Michael VIII Palaeologus (1259-1282) to bring about the reunion of the Eastern and Western Churches at the Council of Lyons (1271), the monastery suffered fresh tribulations. According to tradition, when the supporters of the union returned from Lyons, they invaded the Holy Mountain and attempted to force the monks to embrace their views. The refusal of the Vatopaidi brotherhood resulted in the hanging of the Abbot Euthymius and the drowning of 12 monks in the bay of Kalamitsi, as well as the hanging of the Protos of Karyes, St. Cosmas of Vatopaidi.

Shortly afterwards, however, with the aid of the Palaeologues, the monastery recovered. Andronicus II (1282-1328) regarded it as “from time immemorial among the first and the glorious” and provided it with financial support so that it could return to its “former prosperity and state”.

Throughout its history the monastery has attracted to it, or the area around it, certain major ascetics. Prominent among them are the figures of St. Gregory Palamas, the great hesychast theologian, and his teacher St. Nicodemus, St. Joasaph of Meteora, and St. Sabbas, the ‘fool for Christ’s sake’, whose life was written by his pupil St. Philotheus Coccinus, Patriarch of Constantinople, stand out. These were followed a little later by St. Macarius Macres, subsequently abbot of the Pantocrator Monastery in Constantinople (1431), while during the early years of Turkish rule it sheltered for a while the former Ecumenical Patriarch, Gennadius Scholarius.

Around the year 1500, another Patriarch of Constantinople, St. Niphon, accompanied by his disciples the martyrs Macarius and Joasaph, betook himself to the monastery. It was at this period also that the polymath St. Maximus the Greek, the great missionary to the Russians, was a monk at Vatopaidi. According to the latter’s testimony, the monastery at that time followed a semi-coenobitic way of life; it functioned, that is to say, as a lavra. The oldest act converting it into a coenobium at this period dates from 1449. How long it remained idiorrhythmic is unknown. In the year 1574, the monastery was again converted into a coenobium, on the initiative of Silvester, Patriarch of Alexandria.

The setting up of the Athonite School in 1748 was Vatopaidi’s greatest contribution to the interests of the enslaved nation. The building of the school and its operation were undertaken in full by the monastery at a period when it faced major economic problems because of the crippling taxation imposed by the Turkish authorities.

The Athonite School was the biggest Greek school in the Greek world under Turkish occupation, the number of pupils reaching 200. Its first headmaster was the hierodeacon Neofytos Kafsokalyvitis. In 1750, the Patriarch of Constantinople, Cyril V (1748-1757), issued a sigillium in which he announced to the Christian world the founding of the school and sought financial support for it. At the same time, the monastery sent to Thessaloniki the hieromonk Joasaph with sacred relics to collect subscriptions for the school. After the resignation of Neofytos, the running of the school was taken over by the ‘Great Teacher of the Nation’ Evyenios Voulgaris, while the teachers included the hierodeacons Kyprianos Kyprios, afterwards Patriarch of Alexandria (1766-1783), Nikolaos Tzertzoulis and Panayotis Palamas. Among the more famous of the school’s pupils were St. Cosmas of Aetolia, the national hero Righas Ferraios, the scholar and writer Sergios Makraios, the teacher losipos Misiodax, and the theologian Athanasios of Paros. St. Nicodemus the Athonite and Adamantios Koraes were among those who toiled to ensure its smooth operation.

Vatopaidi has a history of supporting various causes, and has continued in more modern times to give generously to philanthropic causes. In 1880, the monastery donated 3,700 pounds for the building of the Great School of the Nation and in 1908 gave the sum of 5,000 pounds to the Theological School of Chalki. In 1912, it undertook the building of the School of Languages in Constantinople.

During celebrations for the thousandth anniversary of the Holy Mountain in 1963, the monastery was visited by the then Ecumenical Patriarch, Athenagoras, King Paul and other distinguished guests.

A decisive point in the monastery’s recent history was its remanning in 1987 by a group of monks led by the elder Joseph Spilaiotis (’the cave dweller’), from Aghiou Pavlou Monastery’s Nea Skete. Moreover, following a resolution on the part of the fathers of the monastery and with a sigillium from the late Ecumenical Patriarch, Demetrius I, in 1989 the monastery returned, after the elapse of centuries, to the coenobitic system of life. Archimandrite Ephraim was elected as first Abbot, and his enthronement took place on the Second Sunday after Easter (29 April) 1990.

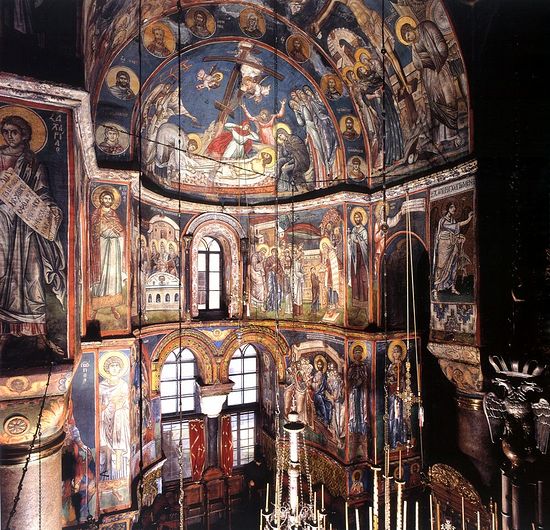

The Katholikon

The katholikon of the Vatopaidi Monastery is an imposing building, dedicated to the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin (feast day 25 March), which has remained virtually unaltered for ten centuries. In terms of architecture, it follows the style of the katholikon of the Megiste Lavra Monastery, with minor deviations. It is divided into five parts:

Exonarthex

Three doors open on to the narthex. The central door is clad with bronze plates on which are embossed plant and other decoration, as well as a depiction of the Annunciation in relief. According to tradition, this door came from the Church of the Holy Wisdom in Thessaloniki and was brought to the monastery after the city was taken by the Turks (1430). The other two doors lead to the chapels of St. Nicholas and St. Demetrius, respectively, on the right and left of the lite. Over the door of the chapel of St. Nicholas is a depiction of the saint in mosaic (14th century), in a rather poor state of preservation. On the right is a large fresco of the Blessed Virgin holding the Holy Child. This fresco replaced the miracle-working icon of the Paramythia, which after the miracle was removed to the chapel of the same name.

Mesonyktikon

This area, between the lite and the main body of the church, takes its name from the night service held in it. At the back, on the right, a tomb of the mid-Byzantine period is preserved, built into the wall. According to tradition, it contains the relics of the monastery’s founders, Athanasius, Nicholas and Antonius, a tradition completely confirmed when the tomb was opened recently. These three figures are portrayed above it in a mural, together with the Emperors Theodosius the Great, Arcadius, Honorius and John Cantacuzene. At the back on the left can be seen, in a fresco, the miraculous icon of Our Lady Antiphonitria.

The mesonyktikon, which, it should be noted, takes this form only at Vatopaidi, was painted in the year 1760.

Nave

This, the main body of the katholikon, preserves for us all the grandeur of Byzantine taste: a magnificent floor, porphyry columns, frescos (see the lite) and mosaics, a carved and gilt wooden iconostasis, innumerable silver and gilt hanging lamps and silver candelabra.

The floor dates from the 10th century and is beautifully inlaid with multicoloured marble. Tradition relates that the four great columns of the central dome, of porphyry, were brought from Italy. Immediately above the columns on the east is a depiction of the Annunciation in mosaics, divided into two, which dates from the mid-eleventh century.

The carved wooden iconostasis, of oak, dating from 1788, replaced an older one of marble, a part of which remains in its original position. The large icons on the screen, work of the Palaeologue era, were gilded by Count Dmitri Nikolayievitch Seremetiev in 1857. In front of the two eastern columns are shrines with fine Byzantine icons of Our Lady Hodegetria and the Hospitality of Abraham. According to tradition, these icons came from the Church of Holy Wisdom in Thessaloniki. Above the abbatial throne on the left (1619) is an icon of the 14th century depicting Sts Peter and Paul, a gift of the Despot Andronicus Palaeologue (1421).

Sanctuary

The sanctuary contains a number of important sacred treasures of the monastery. First among these is the icon of Our Lady Vimatarissa or Ktitorissa, which is in a marble shrine on the synthronon behind the altar. Opposite the icon and on the altar is the cross of Constantine the Great, and, on the right, the silver-overlaid candle, which St. Sabbas, the sacristan, hid together with the icon in the well of the sanctuary for seventy years.

Some 200 other holy relics are contained in a host of extremely valuable silver reliquaries. Among these are the skulls of St. John Chrysostom, St. Gregory the Theologian, St. lakovos the Persian and St. Mercurius, and parts of the skulls of Sts. Sergius, Florus, Pelagia, Theodosia, Arethas, Theodore the Warrior and St. Damian, the metopic bone of the Apostle Andrew, a part of the right hand of the martyr St. Catherine and of St. Stephen the Protomartyr, as well as relics of Sts. Parasceve, Marina, Artemius, Gregory of Decapolis, Procopius and Tryphon. Also preserved complete are the remains of St. Evdokimos of Vatopaidi, which were discovered in 1842 while the cemetery church was being restored. Also in the sanctuary are the skulls of the Patriarchs of Constantinople Maximus IV (1491-1497) and Cyprianus (1707-1714), and of the Patriarch of Antioch Gerasimus (1884-1891), who died and were buried at the monastery.

Chapels

In addition to its main church, the monastery has thirty-one chapels. The three towers of the monastery contain the chapels of the Transfiguration, the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin, and of St. John the Baptist. In the monastery’s various wings there are chapels dedicated to St. Andrew, St. George, Sts. Theodore, St. Menas, the Three Hierarchs, St. Thomas, St. John the Divine, St. John Chrysostom and St. Panteleimon (in the infirmary).

Of particular interest are the chapels of Sts. Cosmas and Damian and of the Holy Girdle, which stand in the spacious courtyard. The former, according to tradition, was built by St. Sabbas, Archbishop of Serbia, for the liturgical needs of the monastery’s Serbian monks. The floor has old marble inlays and on its eastern columns, the figures of Christ and the Blessed Virgin survive from the original frescos.

The Chapel of the Holy Girdle was built on the site of an older church dedicated to St. Constantine, built by the Voivode Neagoe in 1526. The quaint chapel which we see today is a rebuilding by Theofilos Sozopolitis of 1794; the frescos were painted in 1860. The chapel contains two carved wooden lecterns which, tradition relates, were donated to the monastery by the Despot Andronicus IV Palaeologue. On one of these the 24 stanzas of the Akathistos Hymn are depicted and on the other, scenes from the Old Testament. The gilt iconostasis of carved wood dates from the year 1816 and, from the point of view of artistic merit, is considered the third in rank on the Holy Mountain and the finest of the eight such screens in the monastery.

The Treasures of the Monastery

The Holy Girdle of Our Lady

The Girdle of the Blessed Virgin Mary, today divided into three pieces, is the only remaining relic of her earthly life. According to tradition, the girdle was made out of camel hair by the Virgin Mary herself, and after her Dormition, at her Assumption, she gave it to the Apostle Thomas. During the early centuries of the Christian era it was kept at Jerusalem and in the fourth century we hear of it at Zela in Cappadocia. In the same century, Theodosius the Great brought it back to Jerusalem, and from there his son Arcadius took it to Constantinople. There it was originally deposited in the Chalcoprateion church, whence it was transferred by the Emperor Leo to the Vlachernae church (458). During the reign of Leo VI ‘the Wise’ (886-912), it was taken to the Palace, where it cured his sick wife, the Empress Zoe. She, as an act of thanksgiving to the Mother of God, embroidered the whole girdle with gold thread, giving it the appearance which it bears today.

In the 12th century, in the reign of Manuel I Comnenus (1143-1180), the Feast of the Holy Girdle on 31 August was officially introduced; previously it had shared the Feast of the Vesture of the Virgin on 1 July. The Girdle itself remained in Constantinople until the 12th century, when, in the course of a defeat of Isaacius by the Bulgar King Asan (1185), it was stolen and taken to Bulgaria, and from there it later came into the hands of the Serbs. It was presented to Vatopaidi by the Serbian Prince Lazarus I (1372-1389), together with a large piece of the True Cross. Since then it has been kept in the sanctuary of the katholikon. Under Turkish rule, the brethren of the monastery took it on journeys to Crete, Macedonia, Thrace, Constantinople and Asia Minor, to distribute its blessing, to strengthen the morale of the enslaved Greeks and to bring freedom from infectious diseases.

The miracles performed by the Holy Girdle in various ages are innumerable. The following are a very few examples:

At one time, the inhabitants of Ainos called for the presence of the Holy Girdle and the Vatopaidi monks accompanying it received hospitality at the house of a priest, whose wife surreptitiously removed a piece of it. When the fathers embarked to leave, although the sea was calm, the ship remained immobile. The priest’s wife, seeing this strange phenomenon, realized that she had done wrong and gave the monks the piece of the Girdle, whereupon the ship was able to leave immediately. It was because of this event that the second case was made. The piece in question has been kept in this down to the present.

During the time when the Holy Girdle was at Constantinople, a Greek of Galata asked that it should be taken to his house, since his son was seriously ill. When, however, the Holy Girdle arrived at his house, his son was already dead. The monks, however, did not give up hope. They asked to see the dead boy, and as soon as the Girdle was placed on him, he was raised from the dead.

Down to our own times, the Holy Girdle has continued to work many miracles, particularly in the case of infertile women, who, when they request it, are given a piece of cord from the case holding the Girdle and, if they have faith, become pregnant.

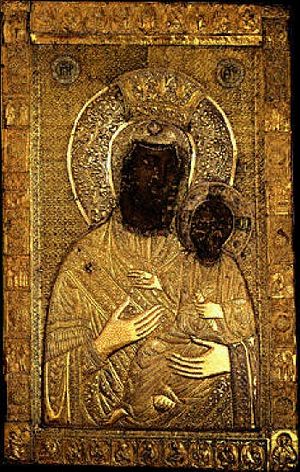

Our Lady Vimatarissa or Ktitorissa

This icon is on the synthronon* of the sanctuary of the katholikon and the following tradition is associated with it.

In the tenth century, during the course of a raid on the monastery by the Arabs, the hierodeacon Sabbas, who was sacristan at the time, managed to hide the icon in the well of the sanctuary, together with the cross of Constantine, placing a lighted candle in front of them. The Arabs plundered the monastery and the deacon Sabbas was carried off as a prisoner to Crete. He gained his liberty seventy years later and returned to the monastery. The younger monks, who knew nothing of the hidden treasures, opened the well on his instructions and found the icon and the cross standing upright on the water and the candle still burning.

This icon is also called Ktitorissa (from ktitor = founder), since its discovery took place during the time of the three founders of the monastery, Athanasius, Nicholas and Antonius. In memory of this, a supplicatory canon to the All-holy Theotokos is sung every Monday evening, and every Tuesday, the Divine Liturgy is celebrated in the katholikon.

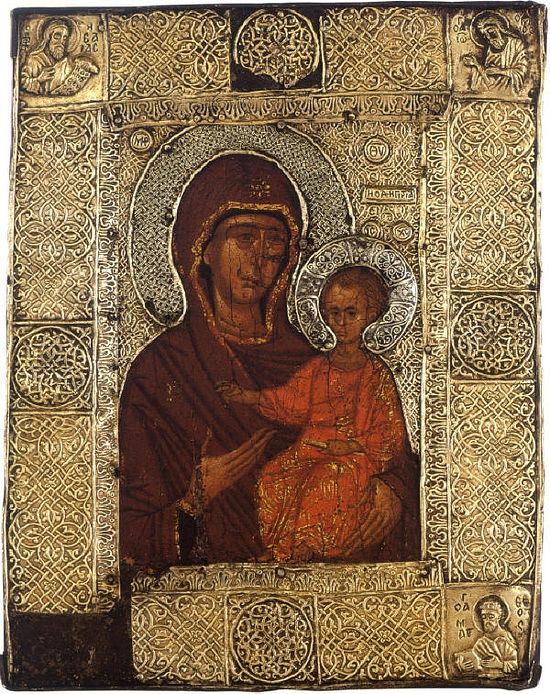

Our Lady Paramythia

Tradition relates that one day, in Byzantine times, as the Abbot was giving the keys to the porter, he heard the following words from the icon: “Do not open the gates of the monastery today, but go up on to the walls and drive off the pirates”. The voice repeated the same words a second time. As he turned to look at the icon, he saw the Holy Child putting His hand over the mouth of His Mother, saying “Do not watch, Mother, over this sinful flock; leave it to pass under the sword of the pirates, for its transgressions have multiplied.” But the Blessed Virgin, taking the hand of Christ and turning her head a little, repeated the same words. The monks immediately hastened to the walls and saw that pirates had indeed encircled the monastery and were awaiting the opening of the gates in order to plunder it. The miraculous intervention of the Theotokos saved the monastery, and the icon has preserved since then traces of the last movements of the figures. From that time on, the monks have kept a perpetually-burning lamp in front of the icon, celebrate in its honor the Divine Liturgy every Friday and chant a supplicatory canon in front of it every day. At one time it was customary for the tonsuring of monks to take place in this chapel.

Our Lady Esphagmeni

This icon is a fresco of the 14th century and is in the narthex of the Chapel of St. Demetrius. Tradition relates that a deacon who was the sacristan of the katholikon used to arrive at the meal in the refectory somewhat late every day, because of his duties. One day, when he asked the monk in charge of the refectory for food, he was refused. The sacristan returned to the church, full of anger and indignation, and said to the icon: “How long do I have to go on serving you and toiling, while you do not care even that I should eat?”, and, with that, he took a knife and plunged it into the face of the Blessed Virgin, from which blood began to run, while he himself was struck blind and fell down like a madman. He remained in that state for three years, occupying a stall opposite the icon, where he wept and implored the Mother of God to forgive him. After three years, the Blessed Virgin appeared to the abbot and told him that she had forgiven the reckless sacristan and would restore his health, but that the hand which had committed the sacrilege would be condemned at the Second Coming of the Lord. When the monk died and the time came, according to the customs of the Holy Mountain, for the disinterring of his remains, it was found that although the rest of his body had decomposed, his right hand had remained intact and was completely black. The hand of the sacristan is preserved today in the katholikon, but in a very dilapidated state, since Russian pilgrims were given to taking small pieces of it, under the impression that it was a sacred relic.

Our Lady Antiphonitria

This too is a wall painting, in the mesonyktikon of the katholikon. It is so named because a voice was heard from it (antiphonise = ‘it answered back’). Tradition relates that the monastery was once visited by the Empress Placidia, daughter of Theodosius the Great. While she was approaching the katholikon with the intention of entering by the small side door, she heard a voice coming from the icon: “Stay where you are and come no further. How dare you, a woman, come to this place?” The Empress, overcome with fear, asked forgiveness from the Mother of God and left the Holy Mountain immediately. To commemorate this miracle, she paid for the building of the chapel of St Demetrius.

Our Lady Eleousa

The icon of the Eleousa is kept in the same chapel, above the shrine on the left. It dates from the fifteenth century and comes from the Russian skete of St. Andrew, from which it was recently brought to the monastery. According to information given by Gerasimos Smyrnakis, the icon was at one time built into the wall of a mosque in Constantinople which had formerly been a Christian church. It was discovered by some Christian workmen who were repairing the mosque in 1893 and secretly sold to Sofronios, the steward of the skete’s metochiin Galata. From there it was brought by Russian monks to Mount Athos and placed in the kyriakon of the skete of St. Andrew.

Our Lady Elaiovrytissa

This icon dates from the fourteenth century and is in the monastery’s oil store. From there it is taken to the katholikon on the Friday after Pascha, its feast day. Tradition relates the following miracle: at a time when there was a shortage of olive oil in the monastery, the St. Gennadius, who was in charge of the monastery’s oil supplies, began to economize by giving oil only for the needs of the church. The cook, however, complained to the abbot, who ordered Gennadius to be unsparing in giving oil to the brotherhood, putting his trust in the providence of the Lady Theotokos. The Blessed Gennadius went one day to the storeroom and saw the tank running over with oil, which had reached the door. From that time, the icon has emitted a remarkable fragrance.

Our Lady Pyrovolitheisa

This is painted on the wall above the outer gate of the monastery. In 1822, a group of Turkish soldiers arrived at the monastery and one of them, seeing the icon, shot at it, the bullet making a hole in the Virgin’s right hand. As a result of this act, the soldier went mad and hanged himself from an olive tree in front of the monastery. The rest of the Turks were terrified by this divine retribution and left the monastery immediately. Moreover, when the commander of the detachment was told of the act of the soldier, who was his nephew, he ordered that he should be left unburied as a malefactor.

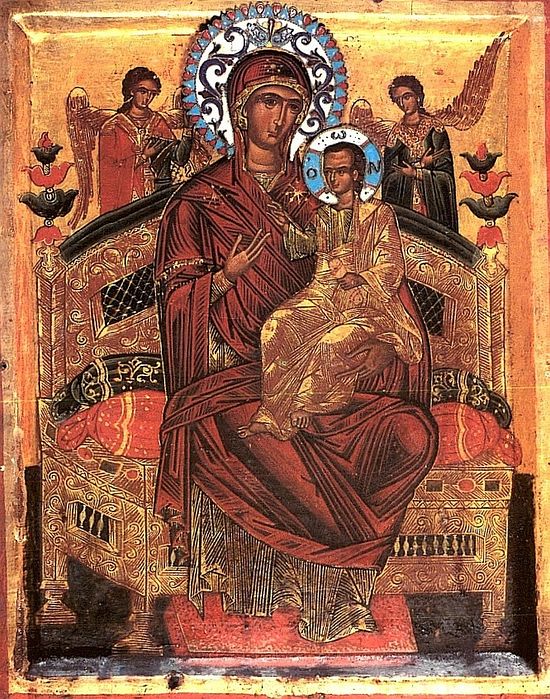

Our Lady Pantanassa

This miracle-working icon dates from the seventeenth century and hangs on the left hand shrine of the eastern column of the katholikon. According to the accounts of the elders of the monastery, the first indication that this icon bestowed especial grace was the following event: one day a young man entered the church and went to reverence the icon. Suddenly the face of the Blessed Virgin shone and some unseen force hurled the young man to the ground. When he came to, he confessed with tears to the fathers that he had been living far from God and that he had been involved with magic. The miraculous intervention of the Virgin resulted in the young man changing his way of life and becoming devout.

This icon also has the property and special grace from God of healing the dreadful affliction of cancer. Large numbers of cancer-sufferers have been healed in recent times following a supplicatory canon chanted before the icon of Our Lady Pantanassa.

Some of the saints of Vatopaidi Monastery

Sabbas, hierodeacon and sacristan (10th century).

Athanasius, Nicholas and Antonius, founders, from Adrianople (10th century), feast day: 17 December.

Sabbas, Archbishop of Serbia (1169-1235), feast day: 14 January.

Symeon, father of St. Sabbas and King of Serbia (1200), feast day: 8 February.

Euthymius, Abbot, and his companions, twelve monk martyrs (1285), feast day: 4 January.

Cosmas, Protos, martyr (1285), feast day: 5 December.

Gennadius, Abbot of the Monastery (14th century), feast day: 20 January.

Neophytus, ‘attendant’ (14th century), feast day: 20 January.

Gennadius, manciple (14th century), feast day: 17 November.

Agapius and Nicodemus, servants of the Blessed Gennadius (14th century).

Sabbas, ‘the fool for Christ’s sake’ (1280-1349).

Nicodemus, teacher of St. Gregory Palamas (13th century), feast day: 11 July.

Gregory Palamas, Archbishop of Thessaloniki (1296-1359), feast day: 14 November.

Theophanes, Metropolitan of Peritheorion (14th century).

Joasaph of Meteora (1394-1401), feast day: 20 April.

Macarius Macres (1391-1431), feast day: 8 January.

Maximus the Greek (1470-1556), feast day: 21 January.

Macarius, martyr, disciple of St. Niphon, Patriarch of Constantinople (1527), feast day: 14 September.

Theophanes, martyr (1559), feast day: 8 June.

Athanasius III of Constantinople (1656), feast day: 2 May.

Agapios from the Skete of Kolitsou and his four blessed companions, feast day: 1 March.

Dionysios, martyr (1822).

Evdokimos ‘the Newly-Found’ (1840), feast day: 5 October

loakeim Papoulakis (1786-1867), feast day: 2 March.

All the saints of Vatopaidi are commemorated by a festal vigil on 10 July.