Source: TheHuffingtonPost.com

By David J. Dunn, PhD

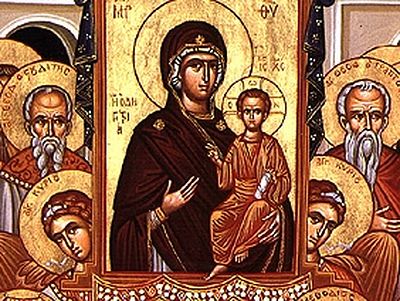

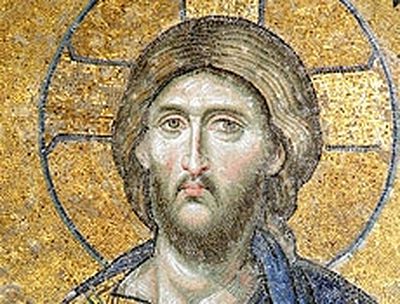

When a visitor steps foot into an Orthodox Church, the first face she will probably see is Jesus. He will be placed on a small stand in the temple (i.e. the "sanctuary"), and as worshipers enter, they will cross themselves, kiss his hand and cross themselves again. I am talking about icons -- religious "pictures" -- which will be scattered throughout the church. The faces of the holy ones seem to come to life behind the flickering light of vigil lamps, hanging from gold or brass chains. Parents will raise their small child up to kiss the feet of some saint. Other worshipers will lay flowers before the icon of the Mother of God and offer special prayers of supplication or thanksgiving.

If this seems like idolatry to you, you are not alone. On the first Sunday of Great Lent (which recently began in the Orthodox Church), we celebrate the "Triumph of Orthodoxy." This marks the end of a long and bloody period in our history, beginning in 726, when Emperor Leo III issued an edict banning icons throughout the Byzantine Empire. Some say he did this because he was influenced by Islam (which rejects images), but few historians agree with that theory. Muslim armies were a threat to the Byzantine Empire, and one tends not to adopt the practices of one's enemies.

Leo probably banned icons because he genuinely thought they were idols. A lot of people today would agree with him. After all, the Bible says, "Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth" (Exodus 20:4). Of course, this verse does not just ban images of holy things. A poster of the solar system on a kid's bedroom wall violates the commandment because it is an image of "heaven above." Jesus-fish stickers are also excluded because they depict something from "the water under the earth." Let me also add that a "graven image" is actually a statue. Thus some translations render "graven" as "carved." So something like this would violate more than just good taste. If we are going to read the Bible in legalistic ways, then technically there is nothing wrong with kissing pictures, because Orthodox Christians reject statuary.

Of course, most Christians who oppose icons do not really have a problem with images themselves. They just don't like the kissing part! The Second Commandment certainly condemns the act of prostrating oneself (bowing) before an image (Leviticus 26:1), and we Orthodox Christians prostrate all the time. But if prostrating before a material image is sinful, then the crowds who bowed before Jesus Christ were all idolaters. All throughout his ministry people crowded around Jesus. They wanted to reach out to touch him, and some were miraculously cured because of it (Matthew 9:20ff). This is a very human thing to do. When we see something holy, we want to touch it. We are also a bit scared to touch it (which is why the woman with the issue of blood snuck up behind Jesus). That is what "reverence" means. Modern iconoclasts might say it is fine to reverence Jesus, but we cannot reverence a picture because Jesus was God. But when the woman with the issue of blood reached out from the crowd to touch Jesus, which "part" of Jesus was she reverencing, the God "part" or the human "part"?

The Triumph of Orthodoxy celebrates the triumph over that kind of thinking. It took a while, but the controversy over images ended in 843 because enough people realized that if they could not kiss icons, then they could not be saved. I am not saying that kissing images of the saints is necessary for one's salvation (though it wouldn't hurt). I'm saying that if we cannot kiss images, then Christ has not come in the flesh for our salvation. The late Lutheran-turned-Orthodox historian, Jaroslav Pelikan, observed that we do not just celebrate the "Triumph of Icons" because iconoclasm was only a symptom of a larger problem: our tendency to think that God and the material world cannot touch each other. Thus some early Gnostics claimed that Jesus was a divine being that only appeared to be human, that when he walked, he did not leave footprints. Later groups (called Arians) said that Jesus was a demigod in human form. Again, they believed that the hands of God could not dirty themselves with the material creation. Thus Jesus was like an incarnate demiurge (in Plato's philosophy), a "go-between" to mediate the infinite distance between God and creation. But if that were true, if Jesus were a demigod, then he is not really human either. Christians cannot pray to him, let alone reach out and be healed by him. They would be worshipping a creature, and that is idolatry!

That is ultimately what ended the controversy over icons. The church realized that if we are to confess that Jesus is fully God and fully human, then we cannot say it is OK to venerate Jesus and not other material objects. After all, the woman who reached out to Jesus did not actually touch his body, just his cloak, but she was healed because through the material object, she worshipped Christ.

To put it another way, where does Jesus' body end and the rest of the world begin? An immunologist friend recently informed me, we actually have more microbes in our bodies than human cells. What cells we have regularly replace themselves, so that our bodies are basically rebuilt twice over the average lifespan. No, we are not impermeable bags of mostly water. We sweat, we pee, we poop, and we bleed. So did Jesus.

That is why we kiss pictures in the Orthodox Church. Like the cloak of Jesus, we do not think the object as divine. Rather, we call them "windows" to heaven, because we encounter Jesus through material objects. A little boy at daycare who misses his mom may carry her picture in his pocket. Sometimes he might take it out to kiss it. He is not an idolater. He just loves his mother. The same is true of a widow woman, who carries on a conversation with her beloved, while gently stroking his tombstone. She is no more an idolater than a Christian who kisses or bows before an icon.

The first Sunday of Lent is a fitting start to his period of more intense fasting and prayer in the Orthodox Church. Processing with icons around the church reminds us that the path from Galilee to Golgotha is a path through matter that ultimately redeems it. So we kiss icons, and we bow before them, because, thanks to Christ, the world he entered and made a part of himself is good and holy. Thus, as St. John Damascene put it, "I do not venerate matter, I venerate the fashioner of matter, who became matter for my sake, and in matter made his abode, and through matter worked my salvation."