While visiting Moscow during the month of June, Archimandrite Irenei (Steenberg), rector of the Sts. Cyril & Athanasius Institute for Orthodox Studies in San Francisco and an Archimandrite of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia, visited Sretensky Monastery for an interview with Pravoslavie.ru. Father Irenei, a scholar of patristic and early Church studies, is also known as the founder of the Monachos internet forum, dedicated to the study of Orthodoxy through its patristic and monastic heritage, and as the host of the “A Word from the Holy Fathers” podcast on Ancient Faith Radio.

This is the second part of our interview with Father Irenei, which focuses chiefly on the state of Orthodox scholarship and sanctity.

Archimandrite Irenei (Steenberg) at Sretensky Seminary

Archimandrite Irenei (Steenberg) at Sretensky Seminary

—In a podcast with Archpriest Josiah Trenham you spoke about what you believe is the poor state of our Orthodox scholarship today. What areas are you concerned about and what do you see as the fundamental need from Orthodox scholarship, and how can we improve our scholarship while remaining true to the Tradition?

—The fundamental problem that we face in Orthodox scholarship is that we as scholars within Orthodoxy (and I speak here very broadly, including students, professors—broadly speaking everyone who’s involved in Orthodox scholarship) tend to be far too influenced by a secular approach to the study of theology of the Church. Very pious people, from a very churched perspective, go about studying and writing about theological themes in a secular way, so that the end result—the studies that we see published, whether on the Fathers of the Church, or the history of the Church, or the life of the Church—regularly end up being indistinguishable in their form and in their structure from studies that would be produced by secular scholars about Plato or about the history of the American Civil War. The theme might be religious, but the way the scholarship is done, the way conclusions are drawn, the way information is presented, is largely according to a common secular model.

An example of this would be the study of the Church Fathers, which is my area of interest. Most of the books that are published about the Fathers of the Church, so-called scholarly books, even by Orthodox writers and by Orthodox printing houses, are really indistinguishable from the sorts of books that anybody could write about the theme of an Orthodox saint. They talk about the history of the person’s life, the dates, the textual traditions, the cultural circumstances, but there’s very little involved, by and large, in this scholarship that deals with the expression of Orthodox theology: that we view the Fathers as being divinely-inspired; that we view the source of their common witness not simply as being a shared textual heritage, but the fact that they are inspired by the breath of the same God. The fact that St. Irenaeus in the second century sounds a great deal like St. Athanasius in the fourth century doesn’t necessarily mean that St. Athanasius is getting all of his information by reading the texts of St. Irenaeus (although he certainly did read some). Far more importantly, these are two men drawn into communion with the same God, Who reveals to them the same truths. This reality, which is so fundamental to our Orthodox spirituality, is almost entirely absent from Orthodox scholarship, and it seems to me that the reason for this is that we are far too keen to accept the parameters, the limits, of secular study, which doesn't involve real theology—it doesn’t frame observations in the realms of divine communion, in discussions of divine inspiration, prayer, and spirituality. These are all treated simply as abstract theological principles; but they never figure in a real way into the way we study, the way we do our scholarship. That to me is the biggest problem we face, and it seems to be pandemic. We find it everywhere. It’s the thing that we most need to address in our studies.

—Would you say there are any notable exceptions? Who would you suggest we read amongst modern scholars?

Fr. John (Krestiankin)

Fr. John (Krestiankin)

—In that same podcast with Fr. Josiah you spoke about your work on a book about St. Cyril of Jerusalem’s Catecheses. What’s the status of that book?

—That book is very, very slow in coming. I regret that I have far too many projects in the works, and this one is my own project, not somebody else’s, and therefore it gets pushed down the list of priorities regularly. I do intend to finish it; it’s about halfway done. It’s on a theme that I find important precisely because I find St. Cyril of Jerusalem a wonderful example of a saint who speaks academically to many of the questions we have over Church history, but who is eminently a pastor, as really all the Fathers are; he in a very obvious way through his catechetical lectures. So I hope that a study on his life can be useful to people today, and I hope that I can complete it before I die—that would be a nice timeline! But we will see.

—Another recent issue that I’ve been seeing lately in the Orthodox world is that some prominent blogs have been discussing universalism: for or against. And it reminds me of some posts of yours from a few years ago on your Monachos forum about the ideas of heaven and hell. You described one popular opinion as, “hell is just heaven experienced differently.” So it seems there are always these questions of the afterlife and questions of God’s mercy and justice and wrath. Why is there so much confusion on these issues? Why are we still unclear, and where can we find the answers?

—You raise a big and a heated point. And you’re right that I have written and spoken about some of these questions, and have been criticized for not following what has become a popular line in modern day discussions. A tremendous amount of the discussion that takes place, particularly on the internet (which really is just the avenue for fruitless discussion), focuses on this idea that has become immensely popular since the mid-1980s that there is no distinction between heaven and hell—that they are one place that is “experienced differently.” Now, this simply is not to be found in the Tradition of the Church, save for, as near as I have ever been able to discern, two paragraphs in the entire history of the Church—one from St. Gregory of Nyssa and one from St. Isaac the Syrian. Two paragraphs ... paragraphs. Not books, not lives, but paragraphs.

Now, there are reasons that people desire to look at the afterlife in this way, and usually those reasons stem from fear, and from a lack of understanding of the love of Christ, the love of God. When we hear the words that the Church consistently employs, like the “fires of hell,” “punishment,” “judgment,”—images that are everywhere in the Scriptures, everywhere in the Liturgy, everywhere in our hymnography, our iconography—we don’t hear those words, we don’t see those images, with the mentality of the Church. We see them and we hear them with the mentality of the twenty-first century, which views them as judgmental, cruel, unkind, uncharitable, unloving. And so we, seeing them in that manner, feel we must explain them away. “Well judgement is ‘mean,’ so we can’t really believe in judgement.” “Hell, an eternal hell, is a cruelty, so we can’t really believe in an eternal hell.” There is an impetus to “explain away” this apparent cruelty.

I understand this. This is perhaps even a pious desire. The problem is that it’s grounded in a misunderstanding. The Church doesn’t view hell as a cruelty. The Church doesn’t view death as a cruelty, or judgment as a cruelty. Our job really ought to be not to come up with a new vision of the afterlife that is more “comfortable” to us, but to conform our understanding to that of the Church; to discover in the authentic language of the Church, the authentic witness of the Church, the authentic love of God. If what we discover in the voice of the Church, in the language and the imagery is a cruel God, then we have not heard the Church’s voice correctly. So this is why I think these questions are perennial. They are raised in every culture, because in every age we misunderstand. In every age the temptation is to hear with the ears of that age rather than with ears of the Church. In every generation we have to conform ourselves anew to the gospel, and that's difficult. That’s hard work. But it’s the work that repays a soul with life.

—It seems like it could be an example of the way we do scholarship that you were speaking about. People on every side can look at the same sources and say, “Here’s a body of quotes; how can I interpret them to make my point?” rather than interpreting them in the light of an active life in the Church. It seems to be a more academic way of approaching it.

We tend to analyze the life of the Church always from the outside, even if we ourselves are Orthodox Christians. Academically we take a step back from that life and we say, “Well, how do we explain this? How do we justify this?” And we justify this action in terms of “objectivity.” I have to take a step back, to be “objective.” But Orthodoxy is not about objectivity. It’s a subjective religion. I am a person; I live in the Church. I am a subject of experiences, of teachings—and it’s only in that experience that I’m able to discern what the Church says. So by “taking a step back,” we are doing precisely the opposite of what we ought. If you want to know the Orthodox teaching on the afterlife, on judgment, on heaven and hell, go through Great Lent—go through the Sunday of the Last Judgment and listen to every hymn. That will teach you. More than anything else, that will teach you how the Church views judgment and heaven and hell. And then, when you question, “Well, that’s a frightful thing, to hear of judgment, to hear of the last days, to hear of the river of fire,” go through the next experience, which is the Sunday of Forgiveness. The liturgical life of the Church will answer your questions far better than any academic study. Not that we shouldn’t have academic studies! But they should be grounded in that same experience, and balanced with that active life.

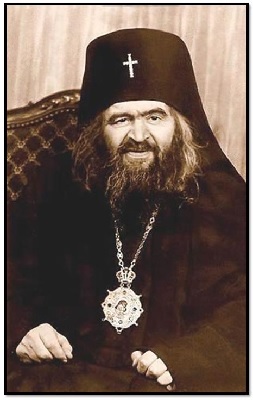

—A totally different question: you serve in San Francisco in the church of the orphanage where St. John (Maximovich) lived, and there in the city you have his relics and his mantia. Could you say a little bit about life with St. John—his presence, his influence?

—The first thing I would say about living with St. John (as I see our lives in San Francisco) is that it is immediately tangible. When one stands before the relics of St. John—his incorrupt relics which are in the cathedral of the Holy Virgin, the Joy of All Who Sorrow—one knows one stands in the presence of a living saint. When one walks into his kellia [cell], where he lived, and sees this tiny room, one is not simply impressed by the smallness or the simplicity of it. You feel St. John standing there with you. I think that all of us who have the blessing to serve in San Francisco, in these many places associated with his life—the New Cathedral, St. Tikhon’s, the Old Cathedral, our many other parishes where he served: the Kazan parish, St. Sergius parish and others—we’re all blessed with this tangible feeling that we are walking together with this saint.

I have to say, personally, that on the one hand this is immensely inspiring and encouraging, and on the other hand it is profoundly condemning. Every day I walk in to the little church of St. Tikhon, which is a house church where St. John lived, where the orphanage was, where his kellia is. Every day I walk in through this ordinary door on what looks like any other building on the street, and immediately I feel the presence of this saint; and I have to say that every day I feel as if he is piously condemning me for my profound weakness in my own pastoral life, for my laxity as a Christian. I don’t say he’s condemning me in the sense of a cruel judge, but as a loving father. To live in the presence of a saint who was such a profound ascetic, who worked miracles in his own lifetime—his miracles did not begin after his death; he was a miracle worker for decades before he departed this life—to serve in the same Church as a man who could heal the sick, who has brought people back from the point of death, who has through his intercessions and blessing caused the barren to give birth—one cannot help but stand in the presence of that legacy and feel entirely unworthy of the Christian calling, of the pastoral life. “What have I done with my life? What am I doing? Where is my repentance? Where is my devotion?” These are the questions that living in his presence causes me to ask. Maybe people of greater spiritual stamina don’t have these questions; but asking them is the inspiration for, I hope, an ever-deepening faith and zeal. When I stand in that little church and I find my mind wandering in the third hour of a vigil, and suddenly I realize I’m standing, literally, in the spot where St. John stood during the seventh or the eighth hour of his vigils—then you catch yourself mid-thought and think, “I really should be more attentive. I can do better.” We have all the miracles of St. John, and they are inspirational and continuous. We see them every day. But at a personal level the most influential dimension of his legacy is his example that one can do better in the Christian life. “If you really wanted to, you could heal the sick. If you really wanted to, you could see into the hearts of others.” That’s what I hear him whispering to me, to all of us.

—Does he ever say, “If you really wanted to you could become all flame?”

St. John Maximovitch

St. John Maximovitch

—It’s so encouraging that we have someone like St. John in our own land.

—Yes.

—Essentially in our own times.

—Yes.

—It’s still possible. The saints aren’t just distant past experiences.

—One of my greatest joys and privileges is serving in that little church where there are still many of “St. John’s children,” which is our term for the children who grew up in his orphanage or in that very house at St. Tikhon’s in San Francisco, having come from Shanghai through the Philippines. These are people who grew up from their childhood in his care, for whom he was their father. I meet many people who knew St. John. He lived not so long ago and there are many, many people alive who knew him. But these are the people who didn’t just know him from a few encounters, who didn’t just serve with him on Sundays in the church. These are people who lived with him morning and evening, every day, their whole lives, until he departed this life; for whom he was a person, not a legend—a person who smiled at their jokes, who scolded them when they were being too silly or too frivolous, who reprimanded them when they were going astray, who touched them gently on the shoulder when they needed consolation, for whom he was a loving father. And yes, to know that such a person lived in our own day, and that there are others like him who live now, some of whom we catch glimpses, but most of whom are hidden from us, is a cause for great inspiration.

—Last question, and we’ve already hit on this here and there. The summer module for the Sts. Cyril and Athanasius Institute is on a study of sanctity and sainthood, and I’ve noticed over the years, in theological discussions, at least in America, and especially on the internet, we often hear things like “the saints can be wrong,” “the saints contradict one another,” “that’s just theologumena.” It strikes me that we don’t really have a good concept of what it really means to be a saint, and we have trouble seeing them as really being different from us in some way. Could you give us a glimpse of what is being discussed in this summer course, and how we ought to approach and think about the saints?

—One of the things that we talk about in this course is that there are two extremes in man's attitudes towards the saints. One extreme is to turn them into idols and to say that the saints are almost ontologically different creatures from normal human beings. They make no mistakes, they live perfect lives, they never commit any errors, almost as if they’re a different category of being. On the other end of the spectrum, the other extreme, is to simply say that they’re no different at all from you or me. They're “ordinary people” in every way. They simply lived a little differently, thought a little differently, but in no way is there any distinction from me or from you. In fact, both of these are errors, and which extreme one goes to depends on personality, background, upbringing, circumstances. By and large the vast majority of people err on the side of idol worship. Most “intellectual” people err on the side of simply viewing the saints as in no way distinct from so-called “ordinary persons.” But the reality lies in the middle. The saints are not ontologically different beings, they are, in the sense of their created nature, ordinary people, though I don’t like that word “ordinary.” “Ordinary” in English sounds quite pedestrian. But ordinary in the sense that they express the same nature as every other human person that has existed or ever will exist in life.

But they are not like you and me, in the sense that they have attained a communion with God that we have not yet attained. Perhaps you have, but I have not yet! And that does affect their being; it doesn’t simply affect their mentality or the way they think. We cannot intellectualize sanctity and say a saint is a saint because he thinks in very theologically correct ways, or he speaks in theologically precise terms. Sanctity is a communion in Christ, and it alters the way a person lives. When one lives in authentic communion with Christ to a high degree, one is able to do the things Christ did, and does. We see saints who with their touch heal the sick. We see saints who can see into the heart and know the thoughts of another person. Not guess, not speculate, but know. We see saints who can raise the dead—St. Peter. We see saints whose shadows were sufficient to remove disease. Now, this is not “just like you and me.” This is different. Does it mean that they're a different type of being? No. What it means is that human life is meant to be lived in communion with God. The life that we live, “ordinary” life, normal day-to-day life, is the life of a debased humanity. The way I live my life is not fully human. If I were fully a human person, as the saints show us the images of full human people, my heart would be continuously aglow with the love of God. The grace of Christ would be manifest in me as it’s manifest in the saint. The fact that it is not so tangibly manifest in me is a sign, not that I haven’t become “superhuman”—the saints are not superhuman, they are human in a way that I have yet to become.

We need to understand that sanctity is not bound up in theological correctness. Of course the saints make mistakes. Sanctity is not a question of being intellectually accurate. There are saints who didn’t know the answers to certain questions, nor was it expected that they should know the answers to certain questions. To be a saint is not suddenly to flip a switch and have an encyclopedic knowledge of all things. What the saints have is a heart in genuine communion with Christ, in authentic communion with Christ, that elevates them to true human people—able, to the degree that God desires, to manifest His attributes in the world, which means that some saints are great miracles workers. If God desires, they will heal the sick, and they will cure the blind. But God may not desire that in the life of another saint. And we have some saints who are not miracle workers but who are no less sanctified. We have some saints who are erudite teachers and write theological tomes. We have some saints who never penned a single text in their entire life, who are completely uneducated, and could not, if asked, answer doctrinal questions. But could they share the true theology of the Church? Absolutely, often to a far higher degree than a theologically-erudite person could, because it’s something lived in their heart. So just as we see that the problems in understanding marriage come from a debased view of marriage, a debased view of the person, so it is with the saints. The problems with our understanding of sanctity come not from false piety, or bad piety. But we don’t understand what sanctity is. Sanctity is the communion of a life in Christ that allows the human person to become simultaneously more human and more divine, which is the whole purpose of our creation.

So again we come back to anthropology—what does it mean to be a person? The true human person is the saint. We often think that Adam is the true person, that we are all sub-Adams. But in the Garden of Paradise, Adam was called to be greater. He was called to a higher communion. It is Christ, the New Adam, Who shows us the full human person. His saints show us the true human person: the person that I am meant to become, that you are meant to become. And if we strive towards this, we will find our redemption.