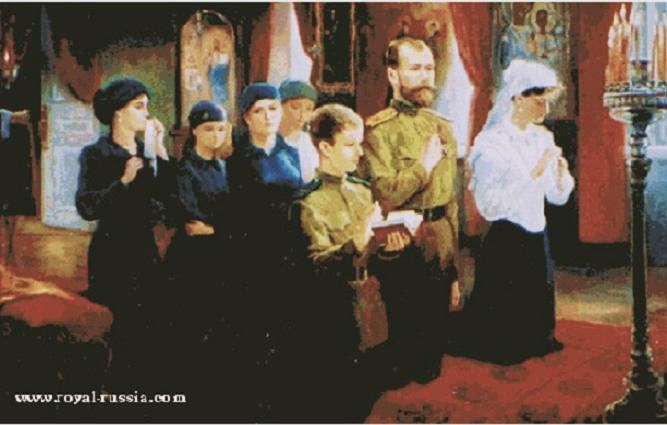

The holy Royal Martyrs are a bulwark, a firm wall of protection for the Russian people and land. Their icons adorn temples everywhere throughout Orthodox Russia and beyond, shining forth with the light of victory. Their people supplicate them, and they are quick to hear. Those who bore the crown are now borne as brilliant jewels on the crown of the Orthodox Church. The Moscow Patriarchate’s 2000 glorification of Tsar Nicholas II and his family—the Tsaritsa Alexandra, the Tsarevich Alexei, and the Grand Duchesses Olga, Tatiana, Maria and Anastasia— along with all the new martyrs and confessors of Russia was a necessary act of repentance from the preceding century, guiding the Church through its continuing resurgence, and one which led to the reunification of the mother Russian Church with its body abroad.

In this sense, in glorifying the Royal Martyrs the Church is simply following in the example that they had offered to us with their lives and in their holy deaths, humbly laying down their throne, and lives, in hopes of preserving the unity of the nation. In the words of Fr. Seraphim Rose, the Tsar was “the first Orthodox layman with a responsibility to give a Christian example to all his subjects,”[1] and in honoring their earthly king the people were led to honor their Heavenly King. Christ also loved the church, and gave himself for it (Eph. 5:25), and in this image, as heaven’s representative on earth, the Tsar also went meekly to his fate as a faithful servant of Christ and of his people. The last Russian Tsar had been born on the day of the Church’s commemoration of the Prophet Job the Much-Suffering, and thereby through God’s providence sensed that his life would likewise know profound suffering—a suffering which he dutifully embraced: “Perhaps an expiatory sacrifice is needed for Russia’s salvation. I will be that sacrifice. May God’s will be done!”[2]

While the memory, glory, and splendor of the noble Tsar and his immediate family are famed throughout the world, there are those amongst his extended family who can also capture our attention.[3] While not a saint, also intriguing is the life of the Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, the younger sister of Tsar Nicholas, memorialized in Ian Vorres’ The Last Grand Duchess (1965). The book was born out of a neighborly friendship: the Grand Duchess, spending her final twelve years in simplicity in Toronto, was wont to invite her neighbor, Ian Vorres, to tea. Vorres just happened to be a writer, and upon learning that his unassuming neighbor was in fact the last surviving Grand Duchess of the Russian royal house he convinced her to grant her blessing to capture her life in writing.

Her Imperial Majesty, Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna

Her Imperial Majesty, Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna

She soon regretted her hasty decision when in 1903 she met Colonel Nikolai Kulikovsky, the true love of her life. It was not until 1916 that her brother, Tsar Nicholas II, granted an annulment, and in the intervening years her marriage to Prince Peter remained unconsummated. During this time the Grand Duchess loved to paint and tend to the garden and she enjoyed an especially close relationship with her brother’s family. While her life, and the book The Last Grand Duchess, can stand on its own as a fascinating tale, Orthodox Christians can especially find much of note stemming from her closeness to the royal family—our Royal Martyrs. Although they have been officially glorified by both the Russian Church Abroad and the Moscow Patriarchate, many unfortunate rumors, lies, and slanders concerning their lives, their martyrdom, and the role of sacred monarchy continue to be perpetuated and sometimes deceive even our own Orthodox Christians.

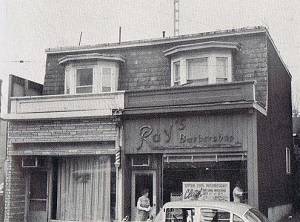

The simple apartment in Toronto's east end, where Grand Duchess Olga died on November 24th, 1960.

The simple apartment in Toronto's east end, where Grand Duchess Olga died on November 24th, 1960.

Sacred Monarchy

Tsar Nicholas II, bearing the Imperial coat of arms of the double-headed eagle, representing the "Byzantine Symphony" of Church and State

Tsar Nicholas II, bearing the Imperial coat of arms of the double-headed eagle, representing the "Byzantine Symphony" of Church and State

It is all but forgotten today that to the Russian masses of my youth the Tsar was chosen by God to rule the country. Their devotion to him embraced their feelings for God and their country. Believe me, I have seen many examples of that truly dedicated affection. It was the main support of the Romanov sovereigns in their unrewarding task of wielding absolute power. Between the crown and the people was a relationship hardly ever understood in the West. That relationship had nothing to do with government or with petty officialdom. The Tsar and the people were bound together by the solemn vows of the Tsar’s coronation oath when he pledged himself to rule, judge, and serve his people. In a Tsar the people and the office were joined together.[4]

This lofty statement should not be simply dismissed as from one biased by familial relations, as her words also adhere to the teachings of the God-bearing saints of the Church. Pondering why Tsar Nicholas II was maligned and finally martyred, St. John Maximovitch answered:

Because he was Tsar, Tsar by the Grace of God. He was the bearer and incarnation of the Orthodox world-view that the Tsar is the servant of God, the Anointed of God, and that to Him he must give an account for the people entrusted to him by destiny, for all his deeds and actions, not only those done personally, but also as Tsar … he was the bearer of the consciousness that the Supreme authority should be obedient to God, should receive sanctification and strength from Him to follow God’s commandments. He was a living incarnation of faith in the Divine Providence that works in the destinies of nations and peoples and directs Rulers faithful to God into good and useful actions. Therefore he was intolerable for the enemies of faith and for those who strive to place human reason and human faculties above everything. [5]

Nor must this be simply dismissed as Russian romanticism about the pre-revolutionary age, for we also find such words enshrined in the Church’s authoritative Seventh Ecumenical Council: “God gave the greatest gift to men: the Priesthood and the Imperial power; the first preserves and watches over the heavenly, while the second rules earthly things by means of just laws,” and again: “The priest is the sanctification and strengthening of the Imperial power, while the Imperial power is the strength and firmness of the priesthood.”[6] Indeed, the Church has traditionally understood the person of the Emperor to be he who now restrains of whom St. Paul wrote, who holds back the mystery of iniquity (2 Thess. 2:7).[7]

And recalling the coronation of Sts. Nicholas and Alexandra the Grand Duchess further stated:

From that very moment Nicky’s responsibility was to God only. I admit that the very idea may sound unreal today, when the absolute power of sovereigns has been so discredited. Yet it will always retain its place in history. The coronation of a Tsar of Russia was a most solemn and binding contract between God and the sovereign, His servant. That is why, after sixty-four years, the memory of it has a special sanctity for me.[8]

Tsar Nicholas II’s Personal Qualities

Taking up the yoke of servitude to God and the people was a serious and heavy responsibility. Upheld by God, the personal circumstances, characteristics and actions of each Emperor yet played a significant role in his reign. It is common enough to hear bewailing of the reign of the sainted last Tsar, supposedly one altogether weak and ineffectual.

While not denying her brother’s imperfections, Grand Duchess Olga offers some explanatory insight into Tsar Nicholas’ imperial formation, and the gravity with which he approached the situation. She recalled her brother approaching her on the verandah, putting his arms around her and sobbing: “Even Alicky [the Empress Alexandra] could not help him. He was in despair. He kept saying that he did not know what would become of us all, that he was wholly unfit to reign. Even at that time I felt instinctively that sensitivity and kindness on their own were not enough for a sovereign to have. And yet Nicky’s unfitness was by no means his fault.” Recalling some of the Sovereign’s finer qualities she noted, “He had intelligence, he had faith and courage” and yet “he was wholly ignorant about governmental matters.” Her brother had been trained as a soldier but insufficiently as a statesman.

She continued:

It was my father’s fault. He would not even have Nicky sit in Council of State until 1893. I can’t tell you why. The mistake was there. I know how my father disliked the mere idea of state matters encroaching on our family life—but, after all, Nicky was his heir. And what a ghastly price was later paid for the mistake. Of course, my father, who had always enjoyed an athlete’s health, could not have foreseen such an early end to his life … But the mistake was there.[9]

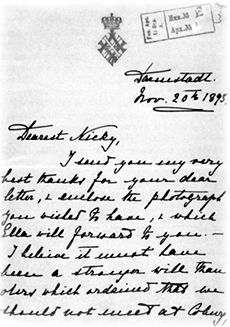

In addition to his sensitivity, kindness, intelligence, faith and courage, Nicholas had also internalized his father’s strong emphasis on family life. Summarizing the testimony of the Grand Duchess, Vorres writes of the Tsar as a man of simple habit and a family life “above reproach,”[10] and the deep, abiding love between the Tsar and his Tsaritsa is widely known and serves as an encouraging example to modern Orthodox Christians weathering the storm of the rapid breakdown of marriage and family life. In one letter addressed to his “Darling Sunny” Nicholas wrote lovingly to Alexandra during a time of war: “My dear, I am longing for you ... Just here, away from Ministers and strangers, we would have plenty of time to talk quietly about various questions, and spend a few cosy hours together.”

A letter of the Tsarina Alexandra to her husband, Tsar Nicholas II

A letter of the Tsarina Alexandra to her husband, Tsar Nicholas II

A story persisted that when the Tsar learned by telegram of the decimation of the Russian navy at Tsusima in May 1905 he crumpled up the telegram and callously returned to his game of tennis. Vorres questioned his royal neighbor on the veracity of this story: “It is a lie – on par with thousands of others!” she cried; “And I know because I was at the palace when the telegram arrived. Both Alicky and I were with him in the room. He turned ashen pale, he trembled and clutched at a chair for support. Alicky broke down and sobbed. The whole palace was plunged into mourning that day.”[12]

Speaking of such times, the Grand Duchess stated, “Perhaps only Alicky and I knew how deeply he suffered and worried. He was always handicapped by the dearth of experienced and disinterested ministers, and all the intellectuals could talk about was revolution and assassination, and didn’t they pay for it?”[13]

Unfortunately, the Tsar’s rule began with such a situation, when, following his coronation, rumor spread that there were not enough gifts for the gathered peasants and a stampede left behind trampled bodies. With his deep sensitivity and his deep faith Nicholas hoped to cancel the evening’s ball and retreat instead to a monastery for a time of prayer and repentance, but his ministers insisted he and Alexandra attend the gala as it had been arranged by the French government. Olga stated: “I know for a fact that neither of them wanted to go. It was done under great pressure from his advisers.” But the newly-crowned gave their day to the people: “I know that both Nicky and Alicky spent the whole of that day in visiting one hospital after another. So did my mother, Aunt Ella, Uncle Serge’s wife, and several others.”[14] And referring to her brother’s generosity in the wake of the tragedy, she asked exasperatedly:

Throughout his reign the Tsar remained no stranger to generosity, and even austerity. He was strict with his own expenses but liberal elsewise. Speaking of the family’s fiscal situation, Nicholas’ sister puts forth a surprising claim: “It sounds tremendous, but it was not. The fiscal year began on 1 January. Often enough Nicky would be broke by autumn.” He had inherited the expense of the upkeep of seven palaces, imperial yachts and trains, the imperial theaters and ballet school, as well as the wage of thousands of court officials who also received presents on Nativity and St. Nicholas’ day, and the allowance for each Grand Duke and Duchess, of which there were many by the time Nicholas ascended the throne. The crown also supported the Academy of Arts and the Academy of Science nearly every year of his reign, and the bulk of orphanages, institutions for the blind, poorhouses, and hospitals depended on the imperial purse.

Vorres continues:

In addition the Tsar’s private chancery was inundated with individual petitions for financial help. A policeman’s widow asking to have her children educated, a brilliant university student requiring a grant to finish his course, a peasant asking for a cow, a fisherman needing a new boat, a clerk’s widow asking for a sum needed to buy a pair of spectacles. The private chancery staff were strictly forbidden to leave a petition unanswered. Once certain inquiries were made, and the case proved to be genuine, the petition was satisfied.

And the Grand Duchess concludes: “Compared with some of the American magnates my brother was a poor man.”[16]

Faith and Self-Sacrifice

The Great Blessing of the Waters at the Neva River on Theophany, 1905

The Great Blessing of the Waters at the Neva River on Theophany, 1905

Our Lord taught us saying This is my commandment, That ye love one another, as I have loved you. Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends (Jn. 15:12-13). Tsar Nicholas and his family would be called upon to show forth this love, and they answered to the call. Although he had an opportunity to flee Russia with his family in the time of the revolution, he chose to stay amongst his people and face whatever awaited him. The time of Russia’s expiatory sacrifice was upon them.

Tsar-Martyr Nicholas II with an icon of St. Seraphim of Sarov

Tsar-Martyr Nicholas II with an icon of St. Seraphim of Sarov

In 1917 Metropolitan Macarius of Moscow saw in a vision the Saviour speaking to Tsar Nicholas: "You see," said the Lord, "two cups in my hands: one is bitter for your people, and the other is sweet for you." In the vision the Tsar begged for the bitter cup. The Saviour then took a large glowing coal from the cup and put it in the Tsar's hands. The Tsar's whole body then began to grow light, until he was shining like a radiant spirit. Then the vision changed to a field of flowers, in the middle of which Nicholas was distributing manna to a multitude of people. A voice spoke: "The Tsar has taken the guilt of the Russian people upon himself and the Russian people is forgiven."[18]

The Tsar, spiritually united at birth to the righteous and long-suffering Prophet Job laid down his life for his friends, and what’s more—even for his enemies, showing the greatest of love. Upon the Cross our Lord called out Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do (Lk. 23:34). From house arrest in Tobolsk in 1918, Grand Duchess Olga, the daughter of the Tsar, passed along the words of her father:

Father asks to have it passed on to all who have remained loyal to him and to those on whom they might have influence, that they not avenge him; he has forgiven and prays for everyone; and not to avenge themselves, but to remember that the evil which is now in the world will become yet more powerful, and that it is not evil which conquers evil, but only love.[19]

The deep faith of the God-crowned Emperor was instilled as well in his family. Such grace-filled words of the Tsar are echoed in his daughter Olga’s own words. A poem copied into one of her notebooks during the family’s time of captivity reads:

Send us, Lord, the patience, in this year of stormy, gloom-filled days, to suffer popular oppression, and the tortures of our hangmen. Give us strength, oh Lord of justice, Our neighbor's evil to forgive, And the Cross so heavy and bloody, with Your humility to meet, In days when enemies rob us, To bear the shame and humiliation, Christ our Savior, help us. Ruler of the world, God of the universe, Bless us with prayer and give our humble soul rest in this unbearable, dreadful hour. At the threshold of the grave, breathe into the lips of Your slaves inhuman strength—to pray meekly for our enemies.

The Empress Alexandra

Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrova seated with the Emphress Alexandra

Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrova seated with the Emphress Alexandra

Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, as we have seen, enjoyed a close relationship with her brother’s family, including with the Tsaritsa Alexandra, about whom to this day persists much unfortunate mythology. Responding to claims made about the Empress, Olga responded with pain of heart: “She is the most maligned Romanov of us all. She has gone down in history so calumniated that I cannot bear reading any more of the lies and insinuations people have written about her.” Most of the family never tried to understand her or to make her feel welcome. Just as the Tsar’s public appearance often left him misunderstood, so too with his beloved wife who faced a particularly difficult time with the Dowager Empress, Marie Fedorovna:

She could do nothing right so far as my mother’s court was concerned. Once I knew she had a dreadful headache; she looked pale when she appeared at dinner, and I heard them say that she was in a bad humour because my mother happened to talk to Nicky about some ministerial appointments. Even in that first year—I remember so well—if Alicky smiled they called it mockery. If she looked grave they said she was angry.[20]

The Tsar was constantly inundated by the domineering demands of those surrounding him, but his oath to the Lord and to his people protected him from falling into despair under the sheer weight of the throne. The Empress Alexandra also stood ever by his side as a firm support in times of joy and in times of sorrow and struggle, although, only a handful, including Grand Duchess Olga, understood this dynamic of their relationship. She recalls:

She was absolutely wonderful to Nicky, especially in those first days when he was crushed by his responsibilities. Her courage undoubtedly saved him. No wonder Nicky always called her Sunny, her childhood name. She undoubtedly remained the only sunshine in the ever-growing darkness of his life. I had tea with them often enough. I remember Nicky coming in—tired, sometimes irritable, his mind in a maze after a day crowded with audiences.

And expressing her deep and enduring admiration for her Empress she continued: “Alicky never said a wrong word or did a wrong thing. I loved to watch her tranquil movements. She never resented my being there.”[21]

The Final Generation

The Tsar was a man of great conviction. His sense of duty and faith was unwavering, his family values impeccable. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for the greater Romanov family of the last generation. While not denying what faults her brother did possess, the Grand Duchess did not hesitate to proclaim, “It is certainly the last generation that helped to bring about the disintegration of the Empire, it is a fact that all through those critical years, the Romanovs, who should have been the staunchest supporters of the throne, did not live up to their standards or to the traditions of the family.” And with the humility of her brother she added incisively, “And that includes myself as well.”[22]

Whereas Nicholas’ father, Alexander III, governed the immense extended family with an iron fist, protecting the throne from any scandalous gossip, his early death saw the demise of this family cohesion. Nicholas, so unjustly styled the “bloody,” ruled with the gentlest hand of all the sovereigns of the great Romanov dynasty. Unruly uncles and cousins did as they pleased and various factions were formed within the family, each with its own egotistical agenda, although united in their disdain for Tsaritsa Alexandra, who conversely faithfully fulfilled her duty before God, nation, and family.

The lives of the Royal Martyrs, defined by service, familial bonds, and a great love for Russia stand in stark contrast to those of the extended Romanov clan:

As I look back on it all I can see that too many of us Romanovs had, as it were, gone to live in a world of self-interest where little mattered except the unending gratification of personal desire and ambition. Nothing proved it better than the appalling marital mess in which the last generation of my family involved themselves. That chain of domestic scandals could not but shock the nation—but did any of them care for the impression they created? Never. A few of them actually did not mind being banished abroad.[23]

Rasputin

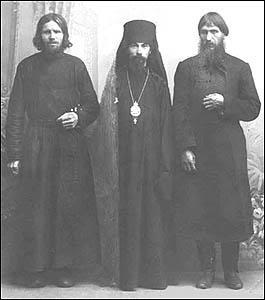

Of course, to attempt to speak accurately of the legacy of the holy Royal Martyrs it is necessary to speak also of Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin, a man of legend whose memory is forever bound up with that of the sainted last family of the house of Romanov, fueled by wild and unfounded myths and accusations. Rasputin was neither a monk nor a priest and he made no claims to be so. He was a father from Siberia who spent little time away from his family and who always sent money to them when he was away. He was not a member of any heretical sect. As so often happens, history speaks to us in extremes. To be sure, Rasputin is not a saint as perhaps some fringe Orthodox or sectarians believe, but neither is he evil incarnate, single-handedly responsible for bringing about the fall of the great Russian empire. As with all things Orthodox, the truth lies in the middle, on the royal path.

Photo taken in 1909 at Verkhotursky monastery of Elder Macarius, Bishop Theophan of Poltava and Grigori E. Rasputin

Photo taken in 1909 at Verkhotursky monastery of Elder Macarius, Bishop Theophan of Poltava and Grigori E. Rasputin

Myths about Rasputin as an evil genius began even in his own lifetime, and undoubtedly as a revolutionary attempt to besmirch the throne. However, Sts. Nicholas and Alexandra were aware of who the man really was:

I think it is high time the man was reduced to his proper size and standing. To Nicky and Alicky he remained what he was—a peasant with a profound faith in God and a gift of healing. There was no mystery whatever about his meetings with the Empress. All those elements were born in the imagination of people who had never met Rasputin at the palace. Someone turned him into a member of the staff. Many others made him monk or priest. He had no position either at court or in the Church. And apart from his undoubted gift of healing, Rasputin was neither as impressive nor as exciting as people think.[26]

While he held no ecclesial position, his faith was genuine. He was first heard of in St. Petersburg in 1904 where St. John of Kronstadt saw him at prayer and was greatly moved by his faith and repentance. According to Olga all who met him considered him a man of God. Thousands of commoners and also bishops believed in the power of his prayer, and his ability to heal the gravely ill Tsarevich is undoubted by the Grand Duchess and all who knew him and the family. He asked favors of the Tsar on behalf of others who petitioned him, but never for himself. Though he could have easily become rich, he chose instead to help the poor and keep only the necessary provisions for his family. He died owning but a Bible, some clothes and a few personal items.[27]

While it is commonly believed that Rasputin enjoyed unchecked influence over the crown, and especially over the Empress who was eternally grateful for the health he several times restored to her son, Olga counters: “Yes, not only did I know Nicky and Alicky far too well to believe any of the ugly rumours, but I also knew the Siberiak [literally ‘man from Siberia’] and knew too the limits of his influence at the palace.”[28] The Sovereign was aware of the rumors and slanders surrounding his family’s relationship to Rasputin and thus banned him from the palace and several times ordered his return to Siberia. His toleration of the man stemmed solely from the help he gave to the inheritor to the throne, Alexei. In her talks with Vorres, the Grand Duchess was quite insistent even that Rasputin had “not a particle of influence” over the Tsar, pointing to some of his letters to Alexandra as proof. True, she admits, while Nicholas was away at Moguilev and Alexandra was alone at Tsarskoe Selo she came to trust more in the counsel of Rasputin, but the Tsar’s appraisal of him remained his own, and for all his devotion to his wife, he appointed and dismissed men against her wishes.[29]

And regarding the vicious and shameful allegations that the Empress Alexandra took part in spiritualist séances arranged by Rasputin, the Grand Duchess answered succinctly: “That would be laughable if it were not wicked. Alicky’s piety may well have been exaggerated, but she was staunchly orthodox and our Church bans all such activities.”[30]

Notions of spiritualism were further fueled by the murder of Rasputin. Referring again to the extended family’s decadence and betrayal of the throne, Olga insisted:

There was just nothing heroic about Rasputin’s murder … It was a murder premeditated most vilely … The murder was so staged as to present Rasputin in the guise of a devil incarnate and his killers as some fairy-tale heroes. That foul murder was the greatest disservice to the one man they had sworn to serve—I mean Nicky. The involvement of two members of the family did nothing but reveal the appalling decadence in the upper social strata. It did more. It created a panic among the peasants. Rasputin was flesh of their flesh and bone of their bone. They felt proud when they heard of him being the Tsarina’s friend. When they heard of his murder they said: “There, let one of us get near the Tsar and the Tsarina, and Princes and Counts must needs kill him out of jealousy. It is always they who will stand between the Tsar and ourselves.”[31]

The Rasputin of popular culture—a sex and power-crazed madman who was nearly unkillable— was largely created by disloyal Russians, eager for revolution to bring down the throne, and in the end the real Rasputin—a simple and faithful peasant who, yes, was not beyond reproach, as Nicholas and Alexandra themselves were aware—was gruesomely brought down.

"The Tsar is a saint and, moreover, one of the greatest saints.”

Grounded in her Orthodox faith, the Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna regarded her brother as God’s anointed Sovereign on earth. His power was not of men, but of God. On one occasion Vorres asked her if she ever prayed for him. She gave the only reply a faithful Orthodox Christian can give:

“Not for him—but to him. He is a martyr.”[32]

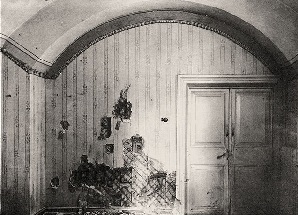

The Ipatiev House cellar room where the royal family was martyred

The Ipatiev House cellar room where the royal family was martyred

"The Tsar is a saint and, moreover, one of the greatest saints. O great saint of Russia, Great-Martyr Nicholas, pray to God for us!"[33]

Verily, and may the prayers of all the Royal Martyrs—Nicholas, Alexandra, Alexei, Olga, Tatiania, Maria and Anastasia be with us.