In the world today, especially in American Christianity, there are divisive debates opposing biblical literalists with those who do not think every scriptural verse was or is meant to be read only literally. Similar debates occurred from the beginnings of Christianity.

Early on it was Christians who claimed it was a Jewish demand to read the Scriptures literally that caused them to fail to see the Christ when He appeared on earth and to fail to believe that Jesus is the promised Messiah. St. Methodius (martyred 311AD) was a prolific author, whose works (and also works attributed to him) come down to us. In the two excerpts below, Methodius is engaged in some anti-Jewish polemics, but that is not what interests me. What I think is relevant to the modern age is that he is quite convinced that if we only read the Scriptures literally (which he says is the Jewish reading of them), we miss the prophecies of God and the ways in which the Old Testament prefigures the events of the new. Only by reading the Scriptures as oriented toward the future does one understand their true importance and meaning. In one work attributed to Methodius, The Banquet of the Ten Virgins, he writes:

“Wherefore let it shame the Jews that they do not perceive the deep things of the Scriptures, thinking that nothing else than outward things are contained in the law and the prophets; for they, intent upon things earthly, have in greater esteem the riches of the world than the wealth which is of the soul.”

10commadments

10commadments

The “deep things of the Scriptures” for Methodius are particularly the way in which the Jewish Scriptures reveal Christ. One need only look at examples of ancient Jewish commentary on the Scriptures to realize the Jews were often extraordinarily creative in their interpretation of biblical texts. But there are examples (Midrashim and the halakhic sections of the Talmud) of Jewish scriptural interpretations which are very legalistic and which focus mostly on life on earth and how to live it. These interpretations are not interested in a future heaven but see Scriptures as teaching us how to live in this world and they seem to be the Jewish interpretations which Methodius has in mind.

Methodius follows a Christian line of thinking which sees the Scriptures as being mainly eschatological – focusing on heaven and leading us to the life in the world to come. This is exactly where he accuses Jewish teachers of failing to recognize “the deep things of the Scriptures” and of being literalistic and worldly. So he offers an example:

“For since the Scriptures are in this way divided that some of them give the likeness of past events, some of them a type of the future, the miserable men, going back, deal with the figures of the future as if they were already things of the past. As in the instance of the immolation of the Lamb, the mystery of which they regard as solely in remembrance of the deliverance of their fathers from Egypt, when, although the first-born of Egypt were smitten, they themselves were preserved by marking the door-posts of their houses with blood. Nor do they understand that by it also the death of Christ is personified, by whose blood souls made safe and sealed shall be preserved from wrath in the burning of the world; whilst the first-born, the sons of Satan, shall be destroyed with an utter destruction by the avenging angels, who shall reverence the seal of the Blood impressed upon the former.” (Methodius, Kindle Location 2302-2312)

So while the Jews see the Passover and Exodus as something which reminds them of the past, and which commemorate God’s saving activities in past history, Methodius points out their deep significance is that they both point out what Christ accomplishes by His death on the cross and they find their fulfillment and meaning in Christ’s saving work. The importance for Methodius of the Passover and Exodus is not to teach us about ancient history, it is in fact to orient our lives to the future, to be prepared for what God is planning to do. If we keep looking to the past (which for him is what a literal reading of the Scriptures does to us), we fail to be looking ahead to what God is now doing and where God is now leading us. As Christians, we are still participating in the Exodus and Passover in and through Jesus Christ, but not as ancient historical events. In Holy Week and Pascha each year, we participate in the Passover and Exodus as part of our experience of salvation in Jesus Christ. We don’t have to look to the past to understand the spiritual importance of these events, for Christ makes them real and accessible to us, and makes them part of our salvation. We need to experience these events as present realities which we participate in, in Christ, rather than think of them as past events.

When one reads the liturgical texts of Holy Week and Pascha and experiences that week, one realizes indeed we move from death to life and from earth to heaven. We experience liturgically and in the present the Passover and Exodus, which is what Methodius is writing about.

“And let these things be said for the sake of example, showing that the Jews have wonderfully fallen from the hope of future good, because they consider things present to be only signs of things already accomplished; whilst they do not perceive that the figures represent images, and images are the representatives of truth.

Methodius teaches the correct reading of Scripture is not to see it as a history book to teach about the past, but all of it is written to direct our lives toward the future, toward the eschaton, toward the Kingdom of God which is to come. The Old Testament is thus mostly a prefiguring of the Christ. It is meant to be read figuratively as it really is a collection of figures and images that help us recognize the Truth – who is Jesus Christ. Read in this way even the Gospels are not mostly about the history or biography of Christ. Rather they too gear us toward life in the world to come.

The celebration of Pascha each year is also not gearing us toward a past event, but gears us to the future. Thus we sing:

Christ IS risen from the dead…

His resurrection is both a current reality which we experience in Pascha, baptism and the Eucharist, but also orients us toward the Kingdom which is still to come. We do not sing, Christ WAS risen from the dead. We are not celebrating a past event, but a current and future reality.

For the law is indeed the figure and the shadow of an image, that is, of the Gospel; but the image, namely, the Gospel, is the representative of truth itself. For the men of olden time and the law foretold to us the characteristics of the Church, and the Church represents those of the new dispensation which is to come.

Though the Church exists now and we live in the Church, yet the Church is “the new dispensation which is to come.” We have a very similar expression in the prayer of the Divine Liturgy in the anaphora in which we give thanks for all the things which have come to pass including “the kingdom which is to come.” Here we encounter this spiritual sense of time in which already we experience the future which is not yet fully realized! We thank God for that future Kingdom which is to come as something God has already given us.

Whence we, having received Christ, saying, “I am the truth,” know that shadows and figures have ceased; and we hasten on to the truth, proclaiming its glorious images. For now we know “in part,” and as it were “through a glass,” since that which is perfect has not yet come to us; namely, the kingdom of heaven and the resurrection, when “that which is in part shall be done away.”

For Methodius, Christians live in this experience of the Kingdom of God which is already available to us and yet not fulfilled. The promises and prophecies of the Old Testament were models and blueprints of what was to happen. Christ is the reality of which these promises and prophecies foretold, and yet still there is more to come which we cannot yet fully experience in this life.

Methodius uses this same concept of the now and not yet as his basis for understanding our own lives and our bodies. In John 2:19-22 we read:

Jesus answered them, “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up.” The Jews then said, “It has taken forty-six years to build this temple, and will you raise it up in three days?” But he spoke of the temple of his body. When therefore he was raised from the dead, his disciples remembered that he had said this; and they believed the scripture and the word which Jesus had spoken.

Methodius uses this Gospel dialogue as the basis for claiming every human body is a tabernacle.

For then will all our tabernacles be firmly set up, when again the body shall rise, with bones again joined and compacted with flesh. Then shall we celebrate truly to the Lord a glad festal-day, when we shall receive eternal tabernacles, no more to perish or be dissolved into the dust of the tomb. Now, our tabernacle was at first fixed in an immoveable state, but was moved by transgression and bent to the earth, God putting an end to sin by means of death, lest man immortal, living a sinner, and sin living in him, should be liable to eternal curse. Wherefore he died, although he had not been created liable to death or corruption, and the soul was separated from the flesh, that sin might perish by death, not being able to live longer in one dead. Whence sin being dead and destroyed, again I shall rise immortal; and I praise God who by means of death frees His sons from death, and I celebrate lawfully to His honor a festal-day, adorning my tabernacle, that is my flesh, with good works, as there did the five virgins with the five-lighted lamps.” (Methodius, The Banquet of the Ten Virgins, Kindle Location 2326-2343)

For Methodius the resurrection of Christ the Savior is not an event gearing us toward the past and leading us to commemorate old events or reenact them. Rather, the sacramental and liturgical life are geared to the future which we begin to live and celebrate now in this world in our daily lives as Christians. Our human bodies have a present, past and future in salvation.

If we read the Scriptures, including the New Testament, as mostly historical records of past events, we miss their very importance. For all Scripture in Methodius’ interpretation gears us to the Kingdom of God. The Old Testament was meant to guide and direct God’s people toward the coming Messiah. But, not only that. For the Old Testament when properly read orients us toward the coming Kingdom of God which is present on earth in Christ and His Church, but which is yet to be fully realized and is still to come. The Old Testament and the New are both point us toward that Kingdom, the eschaton, which is to come. Thus all Scripture is geared toward the future, to the fulfillment of the Kingdom. Rather than anchoring us to the past Scriptures propel us to the future eschaton and life in the world to come. This is the same purpose that Tradition serves in the Church. Unfortunately, just as Methodius accuses the Jews of misunderstanding Scripture by failing to understand them as directing us to the future, so too some Orthodox misunderstand Tradition and see it as anchoring us to the past rather than as propelling us toward the eschaton and life in the world to come. The misreading of Tradition can misdirect us in life.

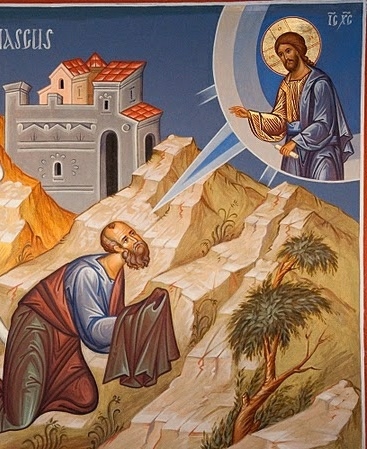

As St. Paul who is the Apostle to us says:

“Brethren, I do not consider that I have made it my own; but one thing I do, forgetting what lies behind and straining forward to what lies ahead, I press on toward the goal for the prize of the upward call of God in Christ Jesus.” (Philippians 3:13-14)