With this Ring, I thee wed, with my Body I thee worship, and with all my worldly Goods I thee endow: In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. Amen. – The Book of Common Prayer (1662)

+++

English is a great language, except when it isn’t. We have an incredible range of vocabulary, both as a legacy of the many languages that have invaded the homeland, as well as its incredible propensity to borrow words. The English vocabulary exceeds 200,000 words, the most of any language in the world (I am told). Thus, it is interesting when English doesn’t quite have a word for something. This is the case with the language of worship.

The phrase quoted above, drawn from the 17th century is an excellent example. Here the word “worship,” clearly does not at all mean that particular honor that is given to God alone but something lesser. This lesser meaning, a form of exceedingly serious honor, can also be found in the honorific title, “Your Worship,” traditionally extended to an English magistrate or mayor.

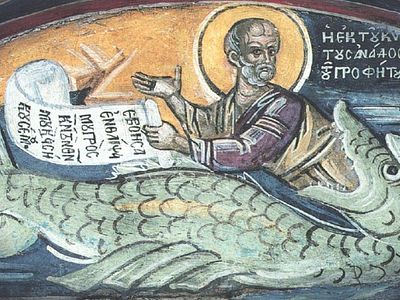

In contemporary English-speaking Orthodoxy, the word comes up now and again with a meaning that is something less than what belongs to God alone. Thus, on the Sunday of the Cross, the Troparion hymn says, “We worship, Thy Cross, O Christ, and Thy resurrection we glorify!” I suspect many people who hear this hymn think that we mean it in its most extreme form and that we are, indeed, offering worship to the Cross as if it were God Himself (we are not).

During the Iconoclast Controversy in the 8th century, the Orthodox Church made a legislative decision about language in which it declared that latreia (latria) belonged to God alone, while proskynesis (dulia) was appropriate to things of honor, such as saints and holy objects (the Cross). Mary is given hyperdulia, a form of veneration that exceeds that of any other created person.

Sometimes the word “adoration” is used to translate latria and is a synonym for worship in its highest sense. And yet, we think nothing of a husband saying that his wife is “adorable” (all babies are adorable).

I suspect that these words (in English) will always be troublesome. Historically, we have never developed a very careful vocabulary. The fact that English became officially Protestant in the 16thcentury has also changed some words, simply in a typical English drive to argue against anything Catholic.

This process has not stopped. Beginning in the 19th century, American evangelical language began to take up the word “save” and “saved” to mean the notion of salvation in an exclusively theological sense in which it is only appropriate to say that “God saves.” Of course, we continue to “save” money, to “save stamps,” and to “save” a drowning man. The New Testament itself uses the word “save” in this normal manner as well.

The Orthodox are frequently criticized for the traditional language of our prayers in which we say, “Most Holy Theotokos, save us!” It is a precise translation of the Greek version of the prayer. Some suggest that we should say something else, “Help us, etc.!” I generally respond to such suggestions that those who are put off by the notion that Mary does anything to “save” us, are put off by our speaking to her in the first place, regardless of what we ask.

And this is the problem with language and worship. In the last analysis, we are speaking to God, and it is for this cause that we should speak the truth, nothing daunting. If it were not our words giving offense, then it would be our actions. Christ Himself was misunderstood, but most consistently by those for whom misunderstanding was an expression of their resistance to God.

The Church speaks in the language of mystery. We can only make known what has been given to us:

But we speak the wisdom of God in a mystery, the hidden wisdom which God ordained before the ages for our glory, (1 Cor. 2:7)

The language of the Church (and thus of the Scriptures) is full of seeming contradiction, paradox, and even apparent foolishness. But such language is quite intentional. That “Mary can save” is a deep mystery (bound up with the mystery of God-become-man). If by some circumlocution we could make a perfectly reasonable statement, giving no offense to the sensibilities of the non-Orthodox, then how could they come to know the truth? For that matter, how will we come to know the truth?

The language of paradox and contradiction has a point. The point lies within the words and beyond the words. However, the words do not act as mere signifiers: they are dynamic interactions, verbal kinetics of self-transcendence. The experience of such language echoes the transcendence of divine communion. It is a verbal icon of theosis.

Ultimately, the truth is made known in silence. It is the nature of traditional Christian language to bring us to silence. We celebrate it. In the great Akathist Hymn to the Mother of God, we declare that she has made the great speakers of this world to be “as mute as fish.” Nothing compares with the eloquence of the Word which she bears in her womb.

We live in an age of argument, frequently with no point in sight. Silence is the end of argument when the Point becomes flesh and dwells among us. Language is useless unless it gets to the point. And the greatest use of language is when the point lies beyond the words.