As I mentioned in the last post, the goal of the Jesus Prayer—indeed a central goal of our spiritual life—is to come to a place of inner stillness. Unlike Buddhism, for the Christian tradition stillness isn’t an end in itself but in the service ofcharity. I need to still my heart before I can discern the will of God for my life and for the lives of those entrusted to my care.

We often hear that love isn’t a feeling but a decision. True enough but it begs the question. What is it we decide when we decide to love?

To love my neighbor doesn’t mean I have warm feelings about him. It doesn’t mean that I like my neighbor. Sometimes my neighbor is rather unlikable. But so what? God doesn’t call us to like each other but to love each other.

God doesn’t love me because I’m good; if I’m good at all it is because God loves me and because I return His love for me.

Love then is objective—it is determined by God. To love my neighbor means that I unite my will to God’s will for him. I love you if I want what God wants for you. And this is where things get complicated.

Aaron Beck, the father of cognitive behavioral therapy, writes that how “we think determines to a large extent whether we will succeed and enjoy life, or even survive.” This isn’t “positive thinking” or of keeping an upbeat attitude so everything will work out. Rather my thinking needs to conform to reality, to the truth of my situation. And so

If our thinking is straightforward and clear, we are better equipped to reach these goals. If it is bogged down by distorted symbolic meanings, illogical reasoning, and erroneous interpretations, we become in effect deaf and blind. Stumbling along without a clear sense of where we are going or what we are doing, we are destined to hurt ourselves and others. As we misjudge and miscommunicate, we inflict pain on both ourselves and our mates and, in turn, bear the brunt of painful retaliations (Love Is Never Enough: How Couples Can Overcome Misunderstanding, 2).

Beck says we are suffering from a “thinking problem.” The Apostle James says the same thing.

Where do wars and fights come from among you? Do they not come from your desires for pleasure that war in your members? You lust and do not have. You murder and covet and cannot obtain. You fight and war. Yet you do not have because you do not ask. You ask and do not receive, because you ask amiss, that you may spend it on your pleasures (James 4:1-3, NKJV).

Recall the last argument you had with someone.

While sometimes you know it’s coming, as often as not we don’t. We don’t even realize we disagree with someone until the argument breaks out. Usually I’m just chatting with someone when—seemingly out of nowhere, it becomes clear that while the other person and I are using the same words, we’re not speaking the same language.

The problem is that I’m not listening to the person but to my own, internal monologue. Basically, I’m talking to myself in the presence of another person. This doesn’t just happen with my neighbor but with God as well.

Actually, I got that backwards. I don’t listen to my neighbor because I don’t listen to God. Yes, I might talk to God—indeed I might talk to God a great deal, constantly even—but how often do I listen to God?

In a fallen world, listening to God is more difficult than I imagine. The neptic fathers in their outline of the process of how I come to commit a sin help us understand why it is so hard to listen to God.

Well before a sin, there is the image/ikon, an abstraction sensory experience. Images arise from any/all of the following:

- the physical world

- other human beings

- my own intraspsychic processes (memory/imagination/anticipation)

- the demonic

Next comes the thought/logismos or my evaluation of the image. This judgment is typically self-referential (what it means for me) and involves an increased level of abstraction. Like images, thoughts arises from any/all of the following:

- other human beings

- my own intraspsychic processes (memory/imagination/anticipation)

- the demonic

Over time, I develop a desire for the object represented by the image. This is what the fathers mean by the passion/pathos. A passion is “that which happens to a person ... an experience undergone passively” (“Glossary” in Philokalia, vol. I, 362). It is often an involuntary movement toward pleasure or away from pain. In more popular language it is my desire for the image and/or what the image represents to me.

Finally, there is action/synkatathesis or my surrender to desire or desire enacted and rewarded. We can also think about this as my assent to the passion. My actions are both the fruit of the passions and serve to reinforce my passions.

Over time my actions become habitual. Vice are those habits of thought and action undermine human flourishing and Christian holiness; virtues are those habits that foster flourishing and holiness. Typically when we read about the passions, we are concerned with vice rather than virtue.

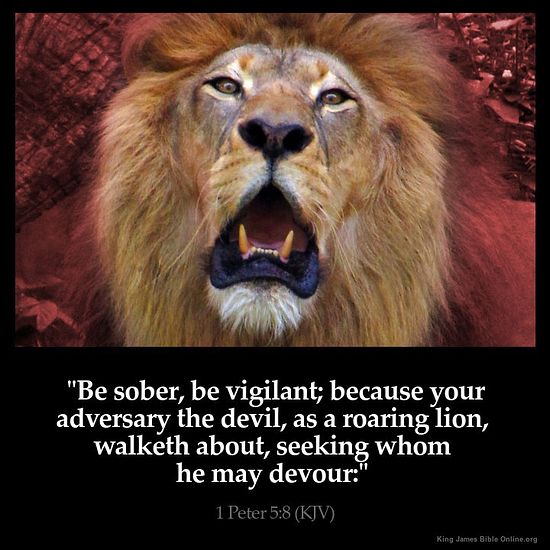

The goal of the spiritual life is to grow more practiced in stilling the process of vice formation and to be less prone to the distractions that come from our internal monologue. Another word for stillness is sobriety.

As this happens we discover, underneath if you will, a deeper, more primordial process—that of the heart and its ability to illumine the world of persons, events and things. In other words, as I still the passions and that internal monologue that sweeps me away, I discover that I am more and more able, and more importantly, willing, to love God with all my heart and soul and to love my neighbor as (and not instead of) myself.

So how does the Jesus Prayer help us to do this? How does the Jesus Prayer help us to listen to God and so help us come “to love one another”? How, in other words, to be cultivate a life of inner stillness and active charity?

In Christ,

+Fr Gregory