Source: Theology That Sticks

February 11, 2016

Like all divorces, this one is going to be messy. The complainant files papers saying she’s trapped in a loveless marriage. There’s neglect and even some abuse. What’s more she wants full custody of the kid and certain rights and privileges to the house and the bank accounts—none of which would exist if the plaintiff hadn’t built them in the first place.

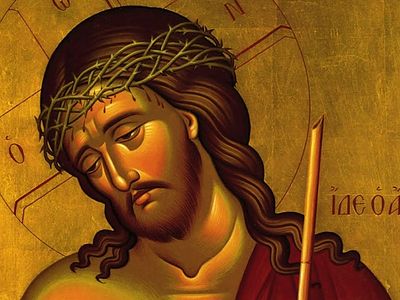

Oh, I forgot. You’re the judge in this case. What do you do? It’s an important question because this is roughly where Christians sit today as people try divorcing Jesus from religion.

The complainant is the solitary Christian, burned out and disenchanted with religion, which the Christian accuses of abandonment and worse. This Christian wants total custody of Jesus, no strings attached, and rights to handle marital assets like doctrine, scripture, and the sacraments any way desired.

But this is where it gets messy. Divorcing Jesus from religion is harder than it looks.

What Jesus and the apostles did

It’s hard to see Jesus as an enemy of, or even disinterested in, religion when He taught doctrines, interpreted scripture, instructed His disciples to pray, appointed leaders within His movement, instituted ritual sacraments like communion and baptism, allowed his followers to call Him rabbi (“teacher”), and said things His followers wrote down and revered as scripture. Sounds pretty religious to me.

Alright, what if we only go that far? What if we allow that Jesus embodied and taught something we might begrudgingly call religion. Shouldn’t we be able to separate that from “institutional” religion? Maybe we need to amend the complaint and divorce Jesus from the Church. Yeah, I’m afraid that’s just as messy.

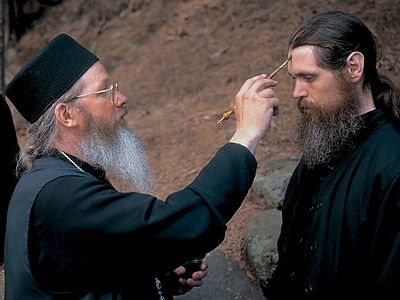

After Jesus’ death and resurrection, His apostles assumed control of what exactly? The New Testament writings assume an institutional Church. The apostles and others in leadership clearly exercise authority. Look the courtroom-like setting of the story of Ananias and Sapphira.

Or look at the Jerusalem council and the presidential role played by Jesus’ own brother, James the Just (see Acts 15). As bishop over the city, his determination regarding how the faith should be practiced was considered binding.

Paul and Peter and the other apostles carried this model wherever they established the Church—appointing bishops, empowering elders (presbyters), writing that Christians in their community should submit themselves to their authority: “Remember your leaders, those who spoke to you the word of God ... Obey your leaders and submit to them; for they are keeping watch over your souls” (Heb 13.7, 17).

We get some pictures of this in action: If the body at Corinth had no institutional authority, for one example, Paul’s direction to excommunicate one of its members (and later direction to restore him) would make no sense.

Let no one put asunder

None of this is to say that religion cannot be distorted or that its leaders cannot abuse adherents. Happens all the time. In the face of distorted and abusive expressions of religion, it’s tempting to think that we can simply separate Jesus from that mess and have Him all to ourselves. But it doesn’t and cannot work that way.

You can’t divorce Jesus from the Church and keep the New Testament because the New Testament becomes a mess of self-contradiction if it doesn’t pertain to a religion that has an institutional expression.

The Church is mixed body, wheat and tares till the end. But the reality of our sinfulness doesn’t preclude obedience and submission as we grow; it’s part of our growth. Extreme circumstances might necessitate disengagement, but they don’t justify abandoning the relationship—even the concept of that relationship—altogether. That’s something worth standing and fighting for.

Divorcing Jesus from religion tears the whole thing apart. No one will walk out of the courtroom the winner.