I have had the good fortune to meet an amazing person: Margarita, Baroness Rida Von Luelsdorff, an exceptional, strong person. Rida has been awarded with the order of Equal-to-the-Apostles St. Olga for her help to the Russian Orthodox Church. Thanks to Rida’s story we can learn more about the eastern branch of the white Russian emigration—that forgotten corner of the Russian diaspora; about those who fled from the Reds, through the province of Xinjiang, Shanghai, and other cities in the East. Little is known about them. Historians have usually paid more attention in their research to the Russian emigrants to Europe or America… The history of the Russian emigration in Xinjiang remains one of the most tragic and untold stories of our [Russian] past.

So, we are driving to Rida’s, past meadows and field not far from Washington, DC—an area free and wide. As we ride, my travelling companion, Peter Vlasov, who at one time worked as an editor for the “Time” TV news program, tells me about the woman who has kindly invited us to visit:

“There are only a few people left like Rida, who went through such terrible trials. She is living history, and her reminiscences are simply priceless. It is hard for me to understand how a person who experienced such unthinkable sufferings, especially as a child… how this child not only survived but also retained her integrity, her correct, unsullied idea of good and evil, her sincerity and depth.”

How was it possible? Humanly of course it’s impossible—it’s possible only for the Lord. She and her family came out of that hell with nothing left but a couple of small icons and crosses. And with her roots in Orthodoxy, she lives and shares her love of life with everyone around her. What gives her the strength? Synergy—the joint effort of God and man in the labor of salvation. This is what gives people like Rida the will to live, keeps them from falling into depression, or some other madness.

We turn off onto an unassuming side road, which curls through the woods (you won’t find your way unless you know where you’re going), and soon a marvelous view of small house opens up before us. Flowers everywhere and beautiful statues—this is where Rida lives. There she is coming out to meet us, sets the table and treats us to a cake that she had just baked. This exquisite, charming lady knows how to do many things herself, and she moves so quickly and deftly that it’s hard to guess her true age—or the horrors she had to live through.

Truly, Rida’s story stuns the imagination and resurrects the events and era that has very few witnesses left in the world—perhaps only a few.

A happy life in Ürümqi

—Respected Rida, would you agree to talk about your life for the readers of Pravoslavie.ru?

—In order for you to understand my childhood, I must tell you about my parents, grandfather and grandmother. My grandfather, Constantine Dubrovsky, was a military doctor under Emperor Nicholas II, and was sent to China. The first mission was in 1905. There was no consulate yet in Ürümqi, the capital of provincial Xinjiang, and this mission took its place.

My grandfather came from the Seven Rivers Cossacks (the town of Verny, now Alma-Ata). My mother was born in Verny. It is interesting that the great-grandfather of Peter Vlasov, who brought you here, Olga, was a leader of the Seven Rivers Cossacks. So both my grandfather and Peter’s were senior officers who served at the same time in the Seven Rivers Cossack army.

Grandfather was a good doctor, and the local people loved him—Chinese, Tatars, and Uigurs. And when he had served his appointed time and returned to his native land, they asked that this doctor be sent to them again. And so grandfather returned to Ürümqi in 1909.

—Rida, allow me to remind our readers generally about what the westernmost province of China, Xinjiang, was like in those days.

This was a buffer zone between two countries, where the rule of the Chinese government existed only formally. The first reason for this was Xinjiang’s distance from Eastern China, and the second was the multi-national population: 60 percent Uigur, who are Muslims, and only twelve percent Chinese, along with Mongols, Kazakhs, Kirghiz, Tatars, Uzbeks, and Tadzhiks.

In the 1920-30s there were also 50,000 Russians living there—Xinjiang became a haven for Russian refugees, White Army officers, and Cossacks. The ataman of the Orenburg Cossack army A. I. Dutov brought with him the miraculous Tabyn icon of the Mother of God.

In May, 1921, an agreement was signed between the Soviet government and the government of Xinjiang to allow the entry of the Red Army for the liquidation of the Whites. The Red Army conducted two operations on the territory of China. Two leaders of the White emigration were murdered: Ataman Dutov and General Bakich. But the Whites still remained a force there.

The situation became acute in 1931—there was an uprising by the Muslim population against Chinese oppression. A slaughter of “infidels” began, which included peaceful civilians. Then a new force joined into the war—White battalions. The training of the Orenburg and Seven Rivers Cossacks, who had gone through many wars, could not be compared with the training of rebels and marauders. Moscow also became involved, not waiting for the conflagration of war to spill over across the border. Thus, in the mountains and deserts of Xinjiang a unique event took place: The “Reds” and “Whites” were fighting on the same side.

After the victory the veterans the White Movement tried to continue their anti-Bolshevik work. They were met with opposition by the OGPU and the Commintern, which had a spy network in Xinjiang. The Cheka pursued the leaders of the White Movement. In Xinjiang, ranks of the regular Red Army were also introduced.

Most of the Russians fled the province in the 1940s, first to Shanghai, and then after the Chinese Communists came to power, to the small Philippine island of Tubabao. Here, on a practically uninhabited island, waiting for permission from the U.S. government, 5.5 thousands Russian refugees lived from 1949 to 1951 under the spiritual leadership of St. John of Shangai.

—My grandfather returned with his family to Ürümqi. He and my grandmother had eighteen children, whom my grandfather received himself at birth. There were six girls, and the rest boys. Only nine children survived, and that despite the fact that my grandfather was a skilled doctor. Scarlet fever and typhus inexorably took many human lives in those years. Grandfather was well-known and respected in Ürümqi not only as a doctor; he organized the building of many homes where Russian refuges were settled.

My mother was the first girl to be born, in 1909. She was beautiful and intelligent. My grandfather himself would consult with her, his own daughter. She was married very young, at age sixteen. Her husband, Poltavsky, was much older than her. They already had children when my mother learned that he was a spy working for the Soviet Cheka. Once night she walked up to him on tiptoes as he was sitting at his desk, typing a list of White leaders for the NKVD. She was so shaken by this that she filed for divorce and waited a long time for it.

In 1931 my future father came to the province; he was the commander of a Cossack brigade. He was given the task of arresting the traitors. He knocked one night at the Poltavskys’ door and my mother open the door to him dressed in her nightgown and robe. Poltavsky was arrested and everyone thought they would shoot him, but out of respect for my grandfather Dubrovsky, his son-in-law was simply exiled and remained alive.

In 1934, mama married a second time. She was twenty-five. I was born in 1935, and then my younger sister, Lydia. We were born in Ürümqi. It is impossible to describe this place, it is so beautiful. Nature in that province is simply wonderful—beautiful mountains and rivers. But most important was the peaceful life. We lived among Tatars, Uigurs, and Kazakhs—almost twenty different nationalities. People respected each other. The Muslim Tatars related to the Orthodox with love. Many of the Tatars themselves were Orthodox.

The Soviets began intruding into the life of Xinjiang province, since it was rich in natural resources and arable land. In 1937, arrests of White emigration leaders began. Mama told me how not long before my grandfather’s arrest, he came to her, walked over to my cradle, took me in his arms and said, “Verunchik (affectionate form of Vera), I am holding this child in my arms for the last time. I have very little time left to live; the Reds are already here. There will be many tears, and many children will be orphaned. But I will say only one thing to you: This child will preserve and save everything that will be left of our family.” “Papa,” my mother asked, “why are you declaring such a heavy burden for this child?” He answered, “She has the strength of spirit.”

How they shot my father and grandfather, and we ended up in prison

Three days later, terrible arrests began. They arrested my father and grandfather. They were accused of taking gold out of Russia and other ridiculous crimes. They held them in prison, tortured them, beat them, then shot them. Mama told me how the Cheka searched the homes of Russians: First they tore down all the icons, trampling them and laughing. Mama was subjected to torture, then they slit her throat and threw down her bleeding, thinking that she was dead. But later the gardener found her in the house. Mama was covered with blood, but still alive. The gardener drove her off, hid her in the church, and then took her to the surgeon. The surgeon was a Jew, named David. Mama heard how he said to the nurse, “Why save this White bandit?! They’re going to shoot her anyway!” But the nurse answered, “You are a doctor. Save her! What happens to her later is not our business.”

Mama survived. She had a marvelous soprano, but after this her voice was always hoarse.

Then she was arrested again, and the rest of us with her—grandmother, my sister and I. For some time we were in jail in Korla. The head of the jail, a Mongol, knew my mother, grandfather and grandmother and gave us extra rations; otherwise we would have died of hunger back then.

Later that Mongol took us out of the prison, loaded us onto a truck, and sent us to Ghulja. He saved us.

—Rida, do you remember these events yourself?

—I don’t remember them well; I was too young. Mama told me about it. My first memories go back probably to that terrible prison, where there was nothing to eat but what our Mongol savior brought us. I remember that there were so many people in the cell that we couldn’t lie down—there was no space. Finally mama found a corner were she was able to put us to bed. Epidemics broke out in the prison—cholera, typhus. They began building gas ovens for the Russian, beating the fascists to it.

I also remember the large truck in which we went to Ghulja. My fist clear memories began from 1941. I was six by then. We lived there in a sort of barrack. People were arrested at night, and they continued to slaughter the Russians.

Murderers were sent to us—a man and a woman, who was pretty, with long, black hair. I remember them. The woman sat at the table; she had been sent to kill mama. Mama was saved again by a miracle. The man drove her somewhere, supposedly to a meeting, and mama saw how he would stop and gulp from a bottle of vodka—apparently it was unpleasant for him to kill a woman while he was sober. Mama was very deductive; she managed to slip out of the homemade truck, get into another and return home. By that time our Russians had come to my grandmother to tell her that those two were murderers sent to kill her. Babushka was horribly worried about mother—and then my mother walks in the door.

Several months went by. The Reds came to Ghulja. Executions began. I remember that one Sudabaev took us under his protection. He was a communist, but he knew grandfather Dubrovsky very well and out of respect for him took care of our family. Sudabaev was later executed for aiding Tsarists. That is what they called us back then—Tsarist.

Mama wanted very much to find her husband and father, and somehow she managed to get permission to go to Ürümqi. Mother and I were already seated in the airplane when two Cheka agents came to us and said, “Madame, you can fly but your mother and daughter have to stay here.” Thus did they keep us as captives. Mama flew off, and I didn’t see her again for five whole years. We lost each other. They told her that we had all died, but she recalled later that her heart told her that we were alive. They left my little, frail sister Lydia with grandmother. But I was tall and strong, and they sent me to the children’s home—we called it the “galleys”.

My life in the “Galleys”

In this workhouse they had gathered children from seven to twelve years of age. We were supposed to work: hauling bricks and earth. We were being “reeducated”, and told that our parents were “white bandits”, that they were scared of a good Communist regime and had abandoned us to our fate. Here I spent almost five years. It was a real hell. We had no beds or bedclothes; we slept on the floor, on straw, with no hygiene whatsoever. We were dirty, hungry, dressed in rags. They would not touch the younger children, but they beat the older ones with belts and sticks. Our house was perpetually filled with screaming and crying.

Once my grandmother came for me and they let me go with her to the cemetery. It was very beautiful there, flowers everywhere—I had never seen such beauty. I asked, “Grandma, who are they burying?” “Your older half-sister Caleria.” When mother divorced Poltavsky, according to Chinese law Caleria was given to her father. She had never been in prison or in a workhouse, and she had lived in excellent conditions—but died at age eighteen from typhus. But I lived in horrible conditions and survived.

Mama told me that Poltavsky lost all of his children, and wrote to her in his old age, “I have paid for my deeds with a broken heart.”

In the workhouse I made a friend, Ruqia. Next to our house was a field where executions were carried out. They shot people right in front of our eyes—apparently to educate us better. Men and youths—traitors to the Communist movement—were stripped to their underwear and killed. We tried not to look at this. But one time, Ruqia recognized one of the men as her father. They shot him right before her eyes.

We went over to the victims; we wanted to cover her father’s body but then the wagon came and the bodies were loaded onto it, then taken a little further away where they were thrown into a pit and burned.

My friend had a small rag doll, and we played with this doll, transporting ourselves this way as if into another world. We would make up tales… Ruqia was two years older than me, and soon I lost my beloved friend—she was given in marriage to some Tatar. Later I learned that Rukhia died in childbirth—she was just a child herself, and this was too much for her young organism.

For these people, a woman was not a person; she was supposed to just work and have babies. There were sartri there, Arabs; we called them locusts—crude and cruel. When people had to be tortured the Chinese wouldn’t do it; they would call the sartri and those men would perform that horrible work.

My other consolation besides my friend Ruqia was Apa, an older woman, who was appointed to watch after us. Apa wore a Tartar’s cap, black Tatar clothes—pants and a sarafan. She had black, greying hair. She was kind, and called me “Ritata”. Apa was Orthodox, and I only later understood this. And I understood what forty days of fasting she was telling us about. She taught us to always help the elderly, the unfortunate, the poor. She told us about goodness, when only evil was reigning all around.

Everyone there was Tatar, they spoke the Tatar language, and I gradually began to forget my native language. I was strong and fit, and Apa often sent me to fetch water or milk. They didn’t give us milk in the workhouse but Apa knew which of the locals we could ask milk for the children, and she would send me.

I remember how I would steal apples—I became an intractable hooligan. I would run to Apa and give apples to all the children, leaving one for myself. And we would eat those apples with black bread.

One day I went to fetch water, and it was very cold out—they have Siberian winters there. I came to the ice hole and filled the first one successfully. But when I filled the second one I couldn’t hold on to it. I lunged after the bucket and started falling into the ice hole. From heaven knows where an old man suddenly appeared next to me. He saved me—literally grabbed me by the feet. He said, “Kyzymka (Tatar for “little girl”), be very careful—you could have died today.”

I spoke Tatar by that time and explained to him that I’ll be punished for that lost bucket. He went off somewhere and then to my unutterable joy, brought me the bucket!

This was a real miracle—after all, at the moment of my fall there was absolutely no one around me. Where did that old man come from?! Now I think: Was it really a man at all? Or was it some spiritual manifestation?

Once Apa sent me for milk four blocks away from our house. As I was walking back with the milk a man in a chaban—a round black Tatar cap with a black scarf followed me. In the dusk I could not see his face well; I could only tell that he was around forty. He said to me, “Kyzymka, kel!” which means, “Little girl, come here!” I obeyed him because he was an older person and went—and he molested me. I didn’t even really understand what was going on—just pain and fear. I remember that I was shaking all over. I was like a little hedgehog, all covered with needles.

In 1943 I was eight years old, and Apa sent me for bread. I was stronger and taller than the others, was always struggling for everything, and Apa knew that I would find bread. She trusted me and would send me more often than the others to get things.

Some military man started stalking me. I increased my pace, and he increased his. I ran, and he ran after me. I already knew what rape was, and tried as hard as I could to run away from him. I felt the rapist gaining on me with an animal fear. I ran under a bridge and hid in the river. It wasn’t deep. Winter was already on, the river was covered with a thin ice crust, and I crashed up to my knees into the icy water. I stood in that icy water in my tattered boots and torn socks, but my shock prevented me from feeling the cold. I stood there for twenty or thirty minutes. The soldier lost me and left, and I climbed out of the river and ran to Apa.

That is how I froze my legs. They turned blue—absolutely blue and swollen. Later they wanted to amputate them but were able to save them. My legs have been cold all my life since then—the blood circulation was disrupted. Terrible pain. My legs hurt for the rest of my life… And this pain keeps me from forgetting the past… I was patient, I endured everything. Here in America the doctors removed the damaged bones from my toes, and there is a scar on each of my toes. I have steel rods there. If I walk too much I suffer terribly from the pain in my legs.

Shanghi: here I learned about St. John

—Dear Rida, how were you able to keep from becoming bitter, to keep your faith in goodness?

—The breaking point of my worldview began thanks to St. John of Shanghai. If it weren’t for him I don’t know what I would have become. Maybe even a criminal… He taught us to return good for evil. Everything human had been so destroyed in us. If it weren’t for Vladyka, I just don’t know if I would have been able to remain human after all we had been though.

This is how I met the saint.

One day my grandmother got permission to take me for one night. When she took me to her little hovel, I saw my little sister, Lida. By that time I practically did not understand Russian, but I remembered how grandma said to us, “Sit quiet—quieter than water and lower than the grass!”

Then grandma led me out to the street, and all three of us were seated in an American truck. We drove a long time to Ürümqi—several days and nights, hidden in bags of potatoes. I remember now how they brought us secretly to Ürümqi, and sent for our mother who had not seen us for five years. Lida and I stood by the gate, and a woman walked by. Then she turned around, threw herself upon us and kissed our hands, embracing us. She just cried, and saying our names over and over…

A little later our aunt Lilia came; she was the wife of a Cheka agent, but she wanted to help my mother. She was later arrested and perished in exile. Aunt Lilia told mother that they would save us: An American truck would come to get us. I remember how they came for us at night with that truck, how they covered it with tarpaulin, and wouldn’t let us bring any of our things with us. Then they seated us in an airplane, and we flew to Lanzhou, then to Shanghai. Grandmother stayed in Ürümqi; they couldn’t take her because there wasn’t enough room in the airplane.

In Shanghai, mama got work as a servant and seamstress. There I remembered the Russian language, and spent three years in the children’s shelter. But that children’s home bore no resemblance to the workhouse in Ghulja. Here we were taken care of by nuns. They taught us the Law of God, and took us to an Orthodox church. There were about 300 girls; the boys lived separately, and there were many of them also. Here I met Vladyka John of Shanghai.

—Could you tell us about St. John of Shanghai in more detail?

—Vladyka did not walk; he flew. You never heard him enter or leave—at all. It was as if someone carried him… When an ordinary person enters a room you hear his footsteps, his clopping, the weight of his body. Vladyka John was bereft of earthly weight! His beautiful black eyes saw through you. I have never seen any such eyes all my life! He read everything in your heart.

Vladyka was very strict. We were woken up early, went to the cathedral, and prayed for a long time at the monastery services. They only fed us after the services were over, and they went on for several hours. This was not a punishment—it was spiritual upbringing. If Vladyka had not taught us restraint and patience, how would we have survived in this world?! There was so much love in him that it began to melt my hardened heart. He prayed for us!

The shelter had its own chapel. Vladyka came to us and served. Once he led me to the altar, gave me his staff, and I stood at the altar with Vladyka’s staff—and I was never so happy!

Vladyka did not sleep nights—he walked the streets went to hospitals, communed the sick, and took care of all the homeless and misfortunate. He never wore shoes, only sandals on bare feet. Vladyka never slept, he would only doze a little sitting on a stool—he would doze for ten minutes and then get up again. In his cell there was a table, four chairs, and a small sofa—very poor. There were icons. That was his life.

The nuns brought me Vladyka’s vestments and klobuk, and I would mend them. I turned out to be an excellent mender! His clothing was very worn. One night I was repairing Vladyka’s klobuk; they had told me that it had to be ready by morning. It was dark, and I put the chair on the table, right under the lamp, and scrupulously mended. And suddenly I felt such tenderness, such blessedness—all these feelings accompanied the appearance of Vladyka John of Shanghai! My soul was filled with such joy! I later saw this with one priest, Fr. Nicholai, but he had only sparks, while Vladyka had it in full force…

He appeared and tapped me on the forehead with his staff. That is how he blessed me with his staff. My tears fell in his presence, and Vladyka said to me, “Always be like you are now!”

I had heard these words before—in a dream. Three days before the Americans had taken us, I saw a strong, clear dream: I was opening the window and a white dove flew in, and I few out the window with it. I was flying, and I saw icons the Most Pure Mother of God and of our Lord Jesus Christ, about Whom I knew so little at the time. Then I felt an affectionate hand on my head and heard a voice, “Always be like you are now!”

I then told my mother about this dream, and she crossed herself and said, “May God grant that we get out of this hell…”

One day later, Aunt Lilia came and told us that an American truck would be waiting for us.

And now Vladyka John was repeating these words from my dream…

Vladyka was clairvoyant. I remember at the cathedral there was always a crowd of beggars. There was one woman who often asked for alms. Once Vladyka went up to her and said, “Aren’t you ashamed of yourself! Isn’t what you have enough for you?!” When this woman died, they found a lot of money under her mattress.

We lived for three years in Shangai.

With St. John on Tubabao

—How did your life come together after Shanghai?

—When the Chinese Communists came to power, a civil war began and the Chinese Red Army began seizing the country. Then we again had to flee. The International Refugee Organization, under the auspices of the U.N., asked the governments of a number of countries to give temporary shelter to the Russian emigrants from Shanghai. But the only country that responded was the Philippine Republic, which offered us the uninhabited part of the tiny island of Tubabao.

In 1949 we were taken to Tubabao island. We travelled a long time there by boat. Of the 5.5 thousand Russians around two thousand were children, and teenagers. I turned sixteen on the island.

Compared to the workhouse this was simply paradise. Crystal clear emerald waves, pure white sand. And it was warm! There were unbelievably beautiful sunrises and sunsets. The sun was wonderful after cold winters and icy rains. I swam like a fish, and darted across the sand. The nature there was unusual: humid tropical forests, palms, rubber trees, bananas, and bamboo. There were a multitude of birds and reptiles living there—little lizards would run around the camp, and even large iguanas would stray in.

Typhoons would often rage on the Philippine islands, but through the prayers of St. John of Shangai, the storms passed around the island during the years we were there. The rainy season lasted from May to November, and there were tropical downpours—something Russians are not used to. It was hot all year, about 45 degrees [centigrade]. The young people were able to bear the heat more easily, but it was hard for the older people. Some fell sick with tropical fever, but there were doctors and medicine.

We lived in tents; these tents were for two, four, twelve, and even for twenty people each. We were give beds and mosquito netting. Kettles were brought for boiling water, along with generators, tableware, and cookware.

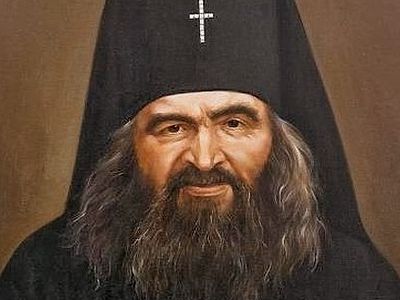

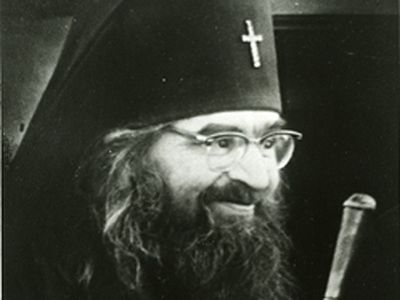

Vladyka John on Tubabao with Gregory Bologov, chairman of the Russian emigrants’ association of Shanghai.

Vladyka John on Tubabao with Gregory Bologov, chairman of the Russian emigrants’ association of Shanghai.

I was a teenager, and much of what was hard about living on the island went by me.

On the island with us was Nikita Valerianovich Moravsky, the author of the book, Tubabao Island, the Last Refuge of the Russian Far-East Emigration; he was a twenty-five-year-old young man at the time and so remembered what the adults had to experience on the island: “On Tubabao we had to adapt ourselves not only to the tropical climate and flora, but we also had to protect ourselves from creatures—poisonous snakes, scorpions, centipedes, and a swarm of mosquitos. Fortunately the nights on Tubabao were cool, but it was impossible to sleep at night without a mosquito net, and bites from poisonous snakes, scorpions, and centipedes could have dangerous consequences. I remember how my neighbor in the two-man tent, Vladimir Krakovstev, accidentally stuck his hand out of the mosquito net and was bitten by a bug. After lying in the hospital for a few days he was released although very weak, and soon died of a heart attack… I was lucky enough to avoid poisonous snake, scorpion, and centipede bites, but like many others I did not escape mosquito fever, which threw me into sweats then shivers for several days. It took much time before I recovered my strength after the fever.”

He also recalled, “The work load in the camp was shared by the men, and the women shared the housework, working in shifts in the kitchen, serving in various offices as typists and secretaries, and as nurses in the hospital... Everyday, several women worked in the kitchen—the head cook and her helpers. They peeled potatoes, prepared other foods for cooking, divided the prepared food into portions, and distributed it to those living in the region. Besides the head cook and her helpers, three men also worked every day in the kitchen—one of them lit the stoves and regulated the fires in them, while two others, who they named jokingly the “kitchen muzhiks”, carried the large kettles with hot soup and pots with the second dish and sweets, as well as carrying out other work that took physical strength…”

He also remembered, “No one on Tubabao went hungry but the food was not tasty, and did not stand out for its nutritional value—something that the children and teenagers felt acutely. In order to feed the children something better and tastier, mothers would when possible fix them something from extra rations, or purchased at the Philippino grocery shops. In the tropics you feel a great need for something hot and spicy, and so the most popular spice on the island was the American Tobasco sauce, with which the lucky ones who received it in packages from the U.S. improved their food… Unboiled water was not potable and so there were boiling kettles in every region… The water supply was limited, and every kettle received only the prescribed amount of canisters. Water was poured into the kettles, and when it boiled the person in charge of the boiler beat a piece of metal and signaled the residents of the neighborhood, “Come and get your water!” A long queue would form at the kettle—everyone needed boiled water… Because of the climate and the difficulty of storing clothes in the proper conditions our suits and dresses were often covered with mold and fell apart. Leather shoes were also ruined. Because of the frequent rains and clay soil, at best sprinkled with pebble, the most practical shoes were wooden clogs that the handy ones made themselves.”

—Dear Rida, do you remember Vladyka John on the island?

—Yes, of course. Vladyka prayed for us. Every evening he walked around the camp and blessed it for the night. His prayers preserved Tubabao from typhoons.

Vladyka was especially attentive to children and young people. On Saturdays he allowed us to have parties, and we danced. At eleven Vladyka would appear at our dances. We would have fun and dance, but at the sight of Vladyka everyone would quiet down and go to receive a blessing. He would ask, “Have you danced your fill?” Now sit down around me.” And he would talk with us, tell us spiritual, edifying stories until one in the morning. He saw each one of us, understood each one, and knew how much each of us could take. He saw everything in a person’s soul.

In the camps there were two tent churches, in honor of Archangel Michael and St. Seraphim of Sarov. Besides them was the large Cathedral of the Mother of God, which stood on the highest place, with a very beautiful view of the sea.

—The island was your temporary refuge…

—Yes, a typhoon could come at any moment, the tents were falling apart, many refugees fell sick with tropical diseases, and people’s strength started to fail. Then they started sending us to different countries. The first part went to South America, then about 1500 went to Australia. The governments of these countries first chose the young and healthy, but no one wanted to take the aged and sick. Later, at Vladyka’s request, the United States also began accepting Russian refugees from the island. After the last group left, the jungle overtook the camp.

From Paraguay to the U.S.

—Where did you and your mother go?

—This was a life lottery. For nine months our ship sailed from country to country in hopes that someone would take us in. At Vladyka’s request, America accepted part of us. But they didn’t accept mama, Lida and I. At first we sailed to Australia. The Australians were interested in young, strong, healthy men who could work a lot. They took our relatives, aunt Liuba, my mother’s sister, uncle Nicholai, and their five sons. But they didn’t take me, Lida, and mama. Country after country, we received one rejection after another. Waves of despair rose in our souls—no one needed us. We arrived in Brazil, Argentina—such were our wanderings.

Finally, Paraguay accepted Lida, mama and I, along with 600 refugees. It was horrible for us there—a repeat of that hell. This country needed workers to work the fields, and we were mostly children, their mothers, and the elderly. We lived in ugly barracks surrounded by woods, with half-naked Indians walking around. The sun was enough to turn one to ash. There were widespread diseases of all possible kinds: malaria, leprosy, syphilis, dysentery. No hygiene, no doctors. An enormous amount of insects: locusts, mosquitos, ticks, and large, flying cockroaches—“kukaracha”.

A few months later we were able to make it on a truck to the capital, Asunción. There was at least some semblance of civilization in the city, although here too poverty reigned; Indians with rings in their noses walked the streets with their donkeys, and people treated them like slaves. Lying in the road before our temporary refuge was a huge anaconda. Asunción was also the refuge for Nazis hiding from the Nuremburg trials, and they lived quite well there.

I went to school; I sat at the very back of the class with the first-graders, and learned Spanish. After lessons I worked as a nanny in one wealthy family. Mama did sewing work on demand and baked her delicious pirogi and cookies in order to pay our rent.

Only later when I had grown up did I manage to make my way to the U.S., and I took mama and Lida with me. The last time I saw Vladyka John of Shanghai was when I had a seven-year-old son. We went to receive Vladyka’s blessing, and he remembered all of us. He said to me, “This is my mender!” I showed Vladyka my boy and introduced him: “This is my son.” And Vladyka called him by name, although no one had ever told him his name. He said, “Hello, Phillip!”

I came to America, as the Russian saying goes, bare as a hare. Here no one was waiting for us with a bowl of porridge, but you could earn it by honest labor. I slept three hours a day and worked very hard. I studied to be a nurse, went to work in health services, and worked twenty-two years in the infection wards of the World Health Organization. I worked as an administrator.

My mother was the president of the sisterhood, which baked pirogi, and with that money built the St. Nicholas Cathedral in Washington. Mama was an outstanding chef; she made remarkable pirogi, and “Napoleon” layer cake. It was hard for me to support the family—my mother and my son, and I took night work. Because I know Chinese, English, French, Portuguese, and Spanish, I would work nights translating documents for the Organization of South American Countries. They would type these documents in the morning.

I married. My married name is Baroness Von Luelsdorff.

Parishioner of the St. Nicholas Cathedral in Washington

I worked for six years in Jerusalem, in the Church of St. Alexander Nevsky, assisting in the building project and repair of the roof. Then I participated in the work of the charitable organization called, “Operation Helping Hand”, heading this organization. For this charitable work, His Holiness Patriarch Alexei awarded me with the Order of Holy Equal-to-the-Apostles Olga in 1992. Now I am a parishioner of the St. Nicholas Cathedral in Washington, DC. And that, if you please, is my whole story…

There were many sorrows in my life. My father and grandfather were tortured and killed, my mother lived through horrible suffering, separation from her children, and the injury inflicted on her throat. I myself experienced rape, hunger, the horrors of the children’s home stripped of rights, poverty, and wandering in foreign lands where no one wanted us. A person who has given himself over to the spirit of darkness is capable of terrible evil. And now I know one thing very well: If you allow into your soul even the remembrance of wrongs, of evil done to you, as soon as you feel hatred for those who injured you, evil begins to grow in your own soul as well. This is the struggle in your soul between God and the devil.

When you remember wrongs, are resentful, when you are at enmity, when you writhe from the offence that you or your loved ones have been dealt, then evil rages right next to you and grows ecstatic, and the human soul dies. But when you forgive you feel the soul being freed, and there is calm, peace and tranquility of the soul. This is such grace! And then you gain strength of spirit and live on. This is what St. John of Shanghai taught us.

—Thank you, dear Rida, for this remarkable conversation!

—May God’s help be with the readers of OrthoChristian.com! May the Lord preserve you!