The Sretensky Monastery publishing house is preparing a book by Archimandrite Tikhon (Shevkunov). It contains true stories that took place during different years, which were later used in the author's sermons.

“And where is this parish of yours?” I asked, glaring at the young priest.

From my tone of voice, the broad-chested individual understood that I was not on his side.

“Not far!” he said to me uninvitingly.

This was the usual reply used to conceal immense distances in our boundless Motherland.

“You see, Giorgi, not far!” Vladyka tried to comfort me.

“Not very far…” the priest said, this time not so cavalier.

“Tell us where,” I said gloomily.

The priest now looked a little unsure of himself.

“An eighteenth century church—you won’t find one like in Russia! The village of Gorelets… Near Kostroma…

My premonition was beginning to come true.

“I see!” said I. “And how far is it from Kostroma to your Gorelets?”

“150 kilometers… Well, more like 200…” the priest admitted honestly. Exactly halfway between Chukhloma and Kologriv.

I started, and began estimating:

“400 kilometers to Kostroma, then 200 more… By the way, Vladyka, do you have any idea what the roads are like between Chukhloma and Kologriv? Listen, Batiushka—have you received a blessing from the bishop of Kostroma for Vladyka to serve there?” I was grasping at my last hope. “After all, he cannot serve in a foreign diocese without a blessing!”

“I would not have asked him without that,” the priest assured me. “I have already received a blessing from my bishop.”

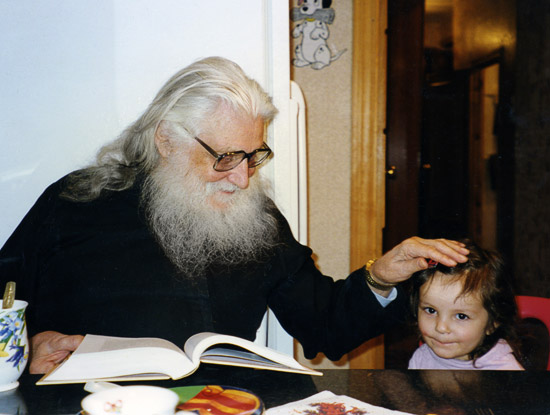

Priest Andrei Voronin and Bishop Basil (Rodzianko).

Priest Andrei Voronin and Bishop Basil (Rodzianko).

Suddenly, the car stopped. Just a few minutes before, there had been an accident on the road—a truck had hit a motorcycle going full speed. A dead man lay in the dust. A young man stood over him, stunned. Next to them stood the downcast truck driver, smoking his cigarette.

Vladyka and his traveling companions quickly got out of the car, but it was too late to help. A moment of triumph of cruel senselessness had burst its way into our world, and the picture of irreparable human woe oppressed each one without exception who happened to be there on the road at that minute.

The young motorcyclist stood clutching his helmet and weeping—the fallen man was his father. Vladyka walked up and embraced the young man’s shoulders.

“I am a priest. If your father was a believer, I can now say the prayers needed for his soul.”

“Yes, yes!” said the young man, beginning to come out of his stupor. He was a believer! Do everything that needs to be done! Father was Orthodox. True, he never went to church—all the churches around here were torn down… But he always said that he has a spiritual father! Please, do everything appropriate!”

We had already brought the priestly vestments out of the car. Vladyka could no longer restrain himself, and carefully asked the young man, “How did it happen that your father was never in church, but had a spiritual father?”

“Yes, here is how it happened… For many years, father listened to religious programs from London. A certain Fr. Vladimir Rodzianko gave them. Father called this batiushka his spiritual father, although he had never seen him in his life.”

Vladyka began to weep, and went down on his knees before his dead spiritual son.

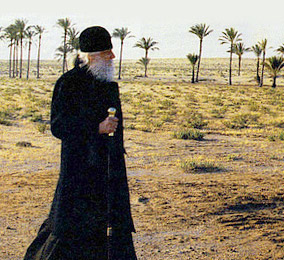

Bishop Basil (Rodzianko) in the desert.

Bishop Basil (Rodzianko) in the desert.

Perhaps Vladyka so loved to travel also because in travels, amidst the unexpected, and even dangers, he felt a particular presence of God. There is a reason why we especially pray “for those who travel by sea, land or air” at every Church service. That is why there also many stories in this modest book that are bound up with traveling. How many amazing, and at times absolutely unique events have happened during travels!

I will tell you honestly, we took advantage of Vladyka’s meek, unmurmuring obedience. In 1992, Viacheslav Mikhailovich Klykov and I, together with our remarkable elderly friend, Professor Nikita Ilych Tolstoy, the chairman of the International Fund for Slavic Literature, prepared a pilgrimage for an entire delegation to the Holy Land, in order to bring the Holy Fire to Russia for the first time. After Pascha night in Jerusalem, pilgrims would depart in a bus for Russia, bringing the Holy Fire through the Orthodox countries located along the way—Cypress, Greece, Yugoslavia, Romania, Bulgaria, The Ukraine, Belorussia, and then to Moscow.

Now the Holy Fire is brought by airplane every year to many cities, in time for the Paschal services. Then, there was a great deal of work done to arrange this travel. The trip would last a whole month. His Holiness Patriarch Alexy sent two archimandrites on this journey—Pankraty, now a bishop and the abbot of Valaam Monastery, and Sergius, who was soon appointed as bishop of Novosibirsk.

One of the participants in this pilgrimage was supposed to be Maria Giorgievna Zhukov, the daughter of Marshal George Zhukov, but she fell sick just before the departure. A person had to be found on short notice who could take her place. The difficulty lay in the fact that visas for so many countries were impossible to get in such a short amount of time. Then, we remembered Vladyka Basil, who had in fact just arrived in Moscow.

To our shame, I have to admit that we did not even think about how difficult it would be for Vladyka, who was already seventy years old, to live an entire month in a bus, and about the fact that he had business to do in Moscow. The main thing was that Vladyka would undoubtedly agree, and the visa question would be taken care of: Vladyka was a British citizen, and his passport would be sufficient for travel in all of the countries on the route. Furthermore, with Vladyka Basil along, the pilgrimage would have a spiritual leader about which they could only dream! We even regretted that we hadn’t thought of him earlier. To crown it all, unlike the other participants, besides English, Vladyka also knew German and French, and even Serbia, Greek, Bulgarian, and a little Romanian. His Holiness Patriarch Alexy blessed him to lead the pilgrimage group, and this filled Vladyka with joy and a feeling of extraordinary responsibility.

(I’ll mention here that Vladyka’s health, thank God, bore it all very well. One of the participants, Alexander Nicolaevich Krutov, bandaged his ailing legs every day, and made sure he did not forget to take his medicine. In Vladyka Basil’s words, Alexander took care of him like his own mother.)

Bishop Basil (Rodzianko) on the ship.

Bishop Basil (Rodzianko) on the ship.

But they began when the pilgrims started crossing state borders. The delegation was supposed to go through border control on a group visa, which had been timely obtained for the whole group. Written on the visa was the name, Maria Giorgievna Zhukova. There was no Bishop Basil (Rodzianko) on it at all.

It all began in Isreal, which is famous for its fierce scrupulousness in border and customs matters. In the airport, the Israeli special services immediately took the unusual group from Russia aside and began calling each member by name. With regard to Archimandrite Pakraty, Archimandrite Sergei, Alexander Nicholaevich Krutov and others, there was no problem. But when they called the name, Maria Giorgievna Zhukova, Vladyka Basil stood up. He smiled amiably to the Israeli agent and bowed.

“How is that?” the agent said. “I called Maria Giorgievna Zhukova.”

“Maria Giorgievna Zhukova—that’s me!” replied Vladyka simple-heartedly.

“How can that be you?” the agent said, taken aback. “Who are you?”

“Who am I? I am a Russian bishop, Basil!”

“Maria Giorgieva Zhukova is a Russian bishop?! This is no place for jokes! What is your name?”

“According to my passport, or…?”

“Of course, according to you passport!” the agent groused.

“According to my passport my name is Vladimir Mikhailovich Rodzianko.”

“Zhukova, Basil, Rodzianko?... Where did you come from?”

“In general, I live in America…” Vladyka began.

“We will explain!” the other members of the delegation tried to get involved in the conversation, but the agent cut them off.

“I ask that others be silent!” Then he turned again to Vladyka. “You say that you are a Russia Bishop, but live for some reason in America? Show me your passport!”

“I only ask you not to get so excited, please!” Vladyka was quite upset that he had become the cause of this young man’s anguish. He handed him the passport and pointed out, “It’s true, my passport is British…”

“What?” the agent barked in indignation and shook the group visa in Vladyka’s face. “And who are you in this document?!”

“How can I tell you?” said Vladyka, amazed at his own self. “The thing is that in this document, I am Maria Giorgievna Zhukova.

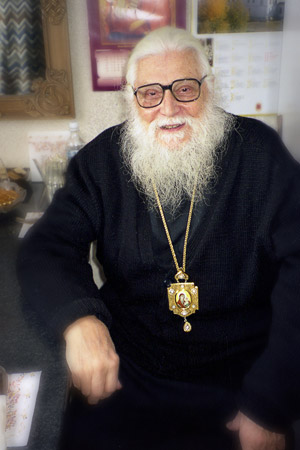

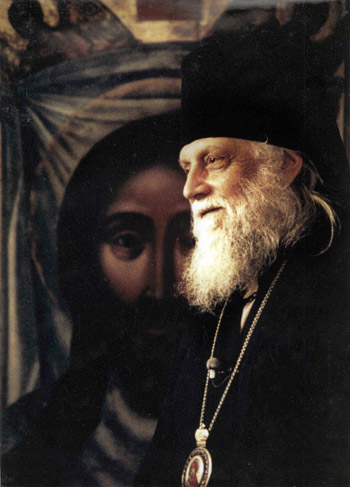

Bishop Basil (Rodzianko).

Bishop Basil (Rodzianko).

For all his meekness, Vladyka did not like it when people yelled at him.

“I am a Russian priest, Bishop Basil!” he pronounced with dignity.

“Bishop Basil? Then who is Vladimir Rodzianko?”

“That is also me.”

“And Maria Giorgievna Zhukova?”

“I am also Maria Giorgievna Zhukova,” Vladyka waived his arms.

“So!... You are a Russian Bishop. And you live?...”

“I live in America.”

“And your passport?”

“My passport is British.”

“But here?”

“Here I am Maria Gieorgievna Zhukova”

This scene repeated itself at every border.

But regardless of all these ordeals, Vladyka Basil was perfectly happy! He was happy that he had been able to fulfill his dream of praying at the Lord’s Sepulchre on Pascha, and that after so many years of separation, he had been able to see his beloved Yugoslavia. He was happy that he had so well fulfilled the important obedience given to him of leading the pilgrimage to the Holy Land, and he was happy to be able to walk next to Patriarch Alexy in the procession from the Dormition Cathedral in the Kremlin to Slavyansky Square, triumphantly bearing a lamp containing the Holy Fire.

Bishop Basil (Rodzianko) carrying the Holy Fire in procession on the feast of Sts. Kirill and Methodiusssss.

Bishop Basil (Rodzianko) carrying the Holy Fire in procession on the feast of Sts. Kirill and Methodiusssss.

Much of the history of the Church in the twentieth century was revealed to us in a new way by one of Vladyka’s stories. Once, an argument arose in his presence on a theme that was popular then—the bishops of the soviet period. Some comments were not just judgmental, but mean and full of biting animosity. Vladyka listened silently to the argument. When the fearless judges of Russian hierarchs turned to him for what they assumed would be support, Vladyka simply related a story from a long time ago.

At the beginning of the ‘sixties, when he was still a priest, to his very London apartment came Metropolitan Nicodim, the head of the Department of External Church Relations of the Moscow Patriarchate. In order to talk they had to lie down on the floor, so that the agents who never let Metropolitan Nicodim out of their sight could not tape the conversation through the window glass.

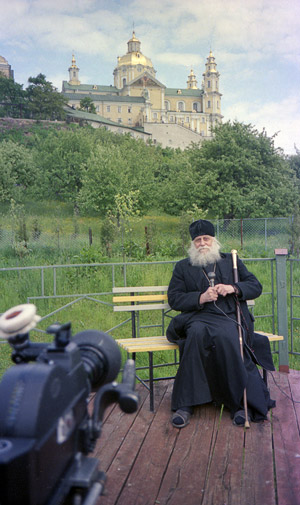

Bishop Basil (Rodzianko) in Pochaev. Photo by the author.

Bishop Basil (Rodzianko) in Pochaev. Photo by the author.

On the very next day, Pochaev became the main theme of the religious programs on the BBC and “Voice of America.” Thousands of letters of protest from all over the world went flying to the soviet government. This influenced the government against their will to again allow the Pochaev Lavra to function.

Once I had the opportunity to be in Pochaev with Vladyka Basil. He was there for the first time. He served the Liturgy, and was able to meet those who had also participated in those dramatic events of thirty years ago.

What else can I recall about Vladyka? Every trip he made to Russia coincided with some extraordinary event. The thousand year anniversary of the Baptism of Russia, the first arrival of the Holy Fire,[1] the pannikhida for the royal family, and the first religious program on central television. As Vladyka himself liked to say, “When I stop praying, coincidences stop happening.”

Vladyka’s arrival in Moscow in 1991 was also no exception. He came that year together with a large delegation from the United States for the first World Congress of Compatriots. Members of the Russian emigration from many different countries, regardless of their individual political convictions, were officially invited for the first time to Moscow. According to the plans of the nation’s leaders, this meeting was supposed to become part of a new stage in the life of post-communist Russia.

A great multitude of people came then! Even emigrants who had never before risked showing their noses in the Soviet Union showed up for this event. There were “unbeaten White Guards” who all their lives had never trusted the soviet authorities one iota. There were even those who had participated in the movement of General Vlasov.[2] How they managed to convince even these people is still a mystery to me. Apparently, no matter how terrifying it was to believe the promises of the soviet emissaries, they all really wanted to see their Motherland!

The hotel “Intourist” was packed. Emmigrants and their descendents strolled around Moscow, looked at the city and the peoples’ faces. They were amazed at the interest people had for them. They were even more amazed at the heightened hope, at times reaching levels of unrestrained fantasy, with which they were received. At that time, there truly were no few beautiful souls who faithfully believed that “the people outside of Russia will help us.” By the way, if there was anyone from the Russian emigration who helped not in word but in deed in the spiritual resurrection of Russia, it was the modest, retired Bishop Basil, along with a few heroic emigrant hierarchs, priests, and laypeople.

Patriarch Alexy II and Bishop Basil (Rodzianko).

Patriarch Alexy II and Bishop Basil (Rodzianko).

Early in the morning of August 20, on the feast of the Transfiguration of the Lord, a bus left the hotel “Intourist” with emigrants from all continents. They were taken to the Kremlin, to the Kutafei Tower. With tears in their eyes, not believing it was true, they walked through the Kremlin gates to the Dormition Cathedral, where His Holiness Patriarch Alexy began the Divine Liturgy together with a host of hierarchs (amongst whom was Vladyka Basil on crutches).

But as we know, it was at that very time, the morning of August, 1991, when an event happened which would be remembered in Russian history by four letters—GKChP.[3] Yes, during the very hour when the Patriarch was praying in the Dormition Cathedral, the government was being overthrown.

At first, no one could understand what was going on. But then, someone shouted in desperation: “I knew it!!! The Bolsheviks have deceived us again! It was a trap!”

The perplexed soldiers in their ranks exchanged startled glances. Desperate shouts rang out from the crowd of emigrants:

“I warned you!!! We shouldn’t have come! A trap! A trap! This was all done intentionally!”

At that time, an officer who had been given orders concerning the Compatriot Congress delegates quickly came closer: they were to be escorted immediately to Lubyanka Square, where buses were already waiting for them, having been sent there when the armed forces arrived at the Kremlin. Then, all the foreigners were supposed to be bussed to the hotel “Intourist.”

“Comrades, do not panic!” the officer said in a commanding voice. “I invite you all, without panic, to go to the Lubyanka[4] in an organized manner! These people will escort you!” At this, the officer pointed to the men with automatic rifles.

“No, no, we don’t want to go to Lubyanka!!!” the emigrants shouted in horror.

“But they are waiting for you there!” the officer was sincerely amazed.

This brought the emigrants to a state of even greater horror.

“No, no!!! Not the Lubyanka! Under no circumstances!” they all shouted.

The officer tried a few more times to call these strange people to common sense, but since all his attempts led to nothing, and the time allowed for the fulfilling of his orders was running out, he gave orders to his soldiers, who energetically pushed the emigrants, at times with their hands, at times with gun barrels, along to the Lubyanka Square.

Everyone was in such shock that they all forgot about Vladyka Basil. He remained on his crutches at the Kutafei Tower, surrounded by soldiers and armored vehicles. At that hour, no one had yet heard about the State Commission for Emergency Situations. The soviet citizens who were near the Kremlin at the time only speculated, but of course, no one knew what was happening. Many recognized Vladyka Basil, and started asking him for explanations. Soon a whole demonstration formed around the perplexed Vladyka Basil, who was a head taller than everyone else.

Meanwhile, the emigrants who ended up at Lubyanka Square understood that they had been brought to their buses and that their next stop was the hotel, and not the KGB dungeons. Then they finally remembered their bishop! Vladyka’s secretary, Marilyn Suizi ran out of the bus and courageously made her way back to the Kremlin, to the tanks and amored vehicles, in this mysterious country, to her beloved Vladyka Basil.

Bishop Basil (Rodzianko), Moscow, 1991.

Bishop Basil (Rodzianko), Moscow, 1991.

Marilyn began to comprehend the entire horror of the situation at hand. Suddenly she noticed that a small, quite appropriate automobile had stopped not far away. “What about that jeep?!” Marilyn exclaimed.

“In the “raven”?” the officer said happily. “That one will do! I’ll go talk to the militia!”

He expressed sincere care for the fate of the foreigners and soon the “raven” drove up to the crowd with Vladyka at the center. Marilyn began pushing her way through to him along with two militia men. Shouting over the crowd and the roaring tanks, Marilyn shouted to Vladyka that a wonderful jeep was waiting to take them to the Lubyanka.

The militia men, the officers, and Marilyn all took hold of Vladyka and dragged him through the crowd. When the people saw this, they were worried.

“What is going on? Where are the militia taking the priest?” the people protested.

When they saw that the elderly batiushka with the cast on his leg was being pushed into the “black raven,” the angered crowd flung themselves to shield Vladyka.

“It’s happening again!!! They are already arresting priests! We will not let you have batiushka! We will form a wall around him!”

“No, no!” shouted Vladyka in desperation, beating off his life-savers. Let me go, please! I want to go to the Lubyanka!”

They barely managed to pull Vladyka with his cast and crutches into the jeep and drive him through the wrathful assembly.

Vladyka looked out the window of the “raven” and only repeated gratefully through his tears, “What people! What people!”

Bishop Basil serving the Liturgy at the Moscow Sretensky Monastery. To the left is Vladyka's cell attendant, Dimitry Glivinsky.

Bishop Basil serving the Liturgy at the Moscow Sretensky Monastery. To the left is Vladyka's cell attendant, Dimitry Glivinsky.

The last time Vladyka came to Moscow, he was very sick. He spent several weeks in bed. Natalia Vasilievna Nesterova, in whose house he was staying, took the utmost care of him. But understanding that Vladyka was probably in Russia for the last time, I asked if the monks and novices of our Sretensky Monastery could take care of him instead of the nurses. After all, it would give the young monks an opportunity to spend time with Vladyka, ask his advice, and ask questions that could only be answered by a spiritually experienced priest, who had gone through much.

Of course, my monks were perhaps not the best nurses. Probably they asked the sick hierarch too many questions and required too much of his strength. But just as it was extremely beneficial for them to spend those days and nights with the wise old bishop, it was also very important for Vladyka to spend time with those who would be replacing him in the Church. He was perfectly happy to be able, even beyond his strength, to answer those questions, instruct, and pass on his experience and knowledge; to fulfill the service for which he lived, and without which he could not imagine himself living.

During his last, cherished journey heavenward—from the earthly homeland to the long-awaited Heavenly Fatherland—Vladyka Basil departed entirely alone. In the morning, they found him without breath, lying on the floor of his room in Washington. Vladyka had lived in it for many years. The room was miniscule, but besides Vladyka it somehow contained also a house chapel, a radio station, the archive of his radio programs for several decades, a table of hospitality open to all, and his office. There was even space for guests: people from Russia sometimes stayed with Vladyka overnight, even for a week.

Even after his death, he did not deny himself the pleasure of a little travel. For a long time, his relatives could not decide where to bury Vladyka. Some proposed Russia—his homeland, after all; some England, next to his matushka, some Serbia, which he loved so much.

Vladyka Basil (Rodzianko), post-mortem photograph.

Vladyka Basil (Rodzianko), post-mortem photograph.

Bishop Basil (Rodzianko).

Bishop Basil (Rodzianko).