The project of modernity was to produce people who believe they should have no story except the story they choose when they had no story. Such a story is called a story of freedom – institutionalized economically as capitalism and politically as democracy. That story, and the institutions that embody it, is the enemy we must attack through Christian preaching.

There is an assumption within our contemporary world that the life we bring into this world doesn’t mean a thing, at least, not at the start. Meaning is something the individual must create for himself/herself. It is, we think, a version of freedom. We are told that if we come into this world with our meaning already established as a given, then we can never be free. Autonomy, being “self-ruled,” is the heart of our contemporary delusion. We have seen this taken to extremes in the recent past. Fundamental givens in life, such as gender and race, are now seen by some as subject to choice. Self-definition (“how I identify”) has become the latest demand in the Modern Project.

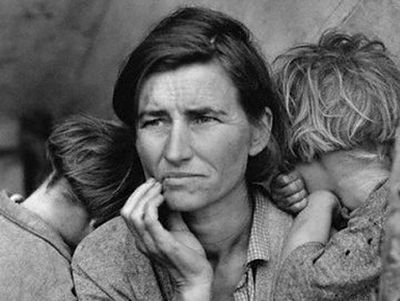

This is an extreme example of Hauerwas’ statement that modernity wants to produce people “who believe they should have no story.” Everyone is his own author, writing the tale of his life in living free verse. It also means that modern people are always on the edge of meaninglessness. When the story you are telling yourself is challenged or falls apart, you are bereft of a reason to live.

I saw an interview recently with a Romanian priest who spoke about his conversion from atheism. He had read deeply in Nietsche, Sartre, and other modern authors, and come to the conclusion that life is simply meaningless marked by interminable suffering. Anyone who finally becomes aware of this, he said, should commit suicide, and the sooner the better. He was obviously in a very dark place. A friend took him to the grave of the great elder, Fr. Arsenie Boca. And as he sat there, without recourse to reason, without praying, without thinking, he simply began to weep. He was astonished at his own weeping. “What’s the matter with me? How can I cry?” But he said, “Something like scales fell from my heart…” And he saw what he could not see before. By some miracle, he saw what he had been given.

Givenness is both at the heart of reality and at the heart of the Orthodox Christian faith. It is at the heart of reality: we do not bring ourselves into existence. Just as our life is a gift, our body is a gift, so our meaning and place in the world are a gift. In none of these things are we self-created.

It is at the heart of our faith: the spiritual expression of embracing the givenness of life isthanksgiving. All that we have, we have received as a gift. The right response to a gift is to give thanks. Everything else is a hardening of the heart.

A necessary delusion of the self-creation of meaning, is that the things we can choose are actually the source of our meaning. And so we invest education, career, family and the like with an ultimacy that does not belong to them. Indeed, it is a form of idolatry.

Saying to a piece of wood,’You are my father,’ And to a rock,`You gave birth to me.’ For they have turned their back to Me, and not their face. But in the time of their trouble They will say,`Arise and save us.’ But where are your gods that you have made for yourselves? Let them arise, If they can save you in the time of your trouble; For according to the number of your cities Are your gods, O Judah. (Jer 2:27-28)

Meaning is something that is always larger than ourselves. It is the-self-in-relation-to-everything. Thus, to create one’s own meaning puts forward the arrogance of defining everything else as well. It is like taking a piece of wood and declaring it to be our God.

The classical Christian life is born of humility and thanksgiving. It is an acknowledgement that we belong to something greater than ourselves and not of our own making. Only with such an acknowledgement do we treat everything and everyone around us with the proper respect and dignity. For if my life is not my own creation, then neither is your life my creation.

Christians recognize and confess that the story of Christ and His Pascha are the meaning of all things. It is the story that God has told the world about itself, about Himself, and about our place in the midst of all things. It has a beginning. It has a place within history. It also has a place that transcends history and offers redemption to every part of the story. Nothing else has to be said.

A rich young man came to Jesus and asked Him, “What must I do to inherit eternal life?” Jesus told him, “Keep the commandments.” But this wasn’t enough for the young man. “I’ve done that. What more can I do?” And Jesus said, “Sell what you have, give it to the poor and come and follow me.”

Keeping the commandments is not a bad place to start. Keeping them is a recognition that there is something greater than my own self. I yield before the law of God. But there is indeed something greater. More than the commandments, there is the radical abandonment of our self for the sake of the Kingdom. There is more than just adhering to a godly standard. The one who gives Himself completely to Christ has set himself in the position that Christ and His Pascha alone will make sense of his life.

If the rich young man kept the commandments, everyone would say, “He’s a good young man.” If he gave everything away they would say, “Is he crazy or something? Why on earth would anyone do something like that? It’s irresponsible! He could have accomplished really great things with all of that money!” And everyone would stare at him and whisper behind his back and shake their heads in disbelief. And he lives for many decades in this same state of poverty. When he dies, they wonder why he wasted his life. In the Kingdom of God, he will sit upon a throne.

What good is a compass that points to itself? It means nothing. It is a compass for people who are going nowhere.