Source: In Serbia

January 27, 2016

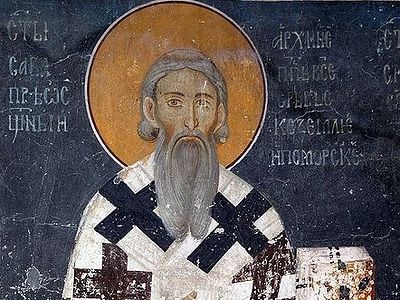

Saint Sava, known as the Illuminator, was a Serbian prince and Orthodox monk, the first Archbishop of the autocephalous Serbian Church, the founder of Serbian law, and a diplomat.

Sava, born Rastko, was the youngest son of Serbian Grand Prince Stefan Nemanja (founder of the Nemanjić dynasty), and ruled the appanage of Hum briefly in 1190–92. He then left for Mount Athos where he became a monk, with the name Sava (Sabbas).

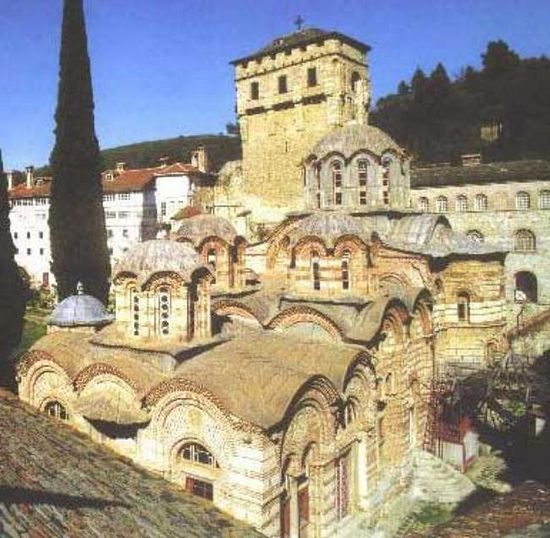

At Athos, he established the monastery of Hilandar, which became one of the most important cultural and religious centres of the Serbian people. In 1219 he was recognized as the first Serbian Archbishop by the Patriarchate, and in the same year he authored the oldest known constitution of Serbia, Zakonopravilo, thus securing full independence; both religious and political. Sava is regarded the founder of Serbian medieval literature.

He is widely considered as one of the most important figures of Serbian history. Saint Sava is canonized and venerated by the Serbian Orthodox Church, as its founder, on January 27. His life has been interpreted in many artistic works from the Middle Ages to modern times. He is the patron saint of Serbia, Serbs, and Serbian education. The Church of Saint Sava in Belgrade is dedicated to him, built where the Ottomans burnt his remains in 1594 during an uprising in which the Serbs used icons of Sava as their war flags; the church is one of the largest church buildings in the world.

Early life

Rastko Nemanjić was born in 1169 or 1174, in Gradina (modern Podgorica, Montenegro). He was the youngest son of Grand Prince Stefan Nemanja and Ana, and was thus part of the first generation of the Nemanjić dynasty; his brothers were Vukan and Stefan.

The brothers received a good education at the Serbian court, in the Byzantine tradition, which Serbia was under great political, cultural and religious influence. Rastko showed himself serious and ascetic; as the youngest son, he was made Prince of Hum at an early age, in ca. 1190. Hum was a province between Neretva and Dubrovnik.

Teodosije the Hilandarian said that Rastko, as a break ruler, was “mild and gentle, kind to everyone, loving the poor as few others, and very respecting of the monastic life”. He was uninterested in fame or wealth, and the throne. After two years, in autumn 1192 or shortly afterwards, Rastko left Hum for Mount Athos. Athonite monks were frequent visitors to the Serbian court – lectures perhaps made him determined to leave.

Upon arriving at Athos, he entered the Russian St. Panteleimon Monastery where he received the monastic name of Sava (Sabbas), and according to tradition it was a Russian monk who was his spiritual guidance, said to have had earlier guested the Serbian court with other Athonite monks. He then entered the Greek Vatopedi monastery. His father tried to persuade him to return to Serbia. Sava replied to his father: “You have accomplished all that a Christian sovereign should do; come now and join me in the true Christian life”.

Stefan Nemanja took his son’s advice – he summoned the assembly at Studenica and abdicated on March 25, 1196, giving the throne to his middle son, Stefan. The next day, Nemanja and his wife Ana took monastic vows. Nemanja took monastic vows under the name Simeon, and stayed in Studenica until leaving for Mount Athos in fall 1197. The arrival of Nemanja was greatly pleasing to Sava and the Athonite community, as Nemanja as a ruler had donated much to the community.

When Sava guested the Byzantine Emperor at Constantinople, he mentioned the neglected and abandoned Hilandar, and asked him that he and his father be given the permit to restore the monastery and grant it to Vatopedi. The Emperor approved, and sent a special letter and much gold to his friend Stefan Nemanja (monk Simeon). Sava then addressed the Protos of Athos, asking them to support the effort that the monastery of Hilandar becomes the haven of the Serb monks. All Athonite monasteries, except Vatopedi, accepted the proposal, and in July 1198 Emperor Alexios III authored a charter which revoked the earlier decision, and instead not only granted Hilandar, but also the other abandoned monasteries in Mileis, to Simeon and Sava, to be a haven and shelter for Serb monks in Athos. The restoration of Hilandar quickly began and Grand Prince Stefan sent money and other necessarities. Stefan issued the founding charter for Hilandar in 1199.

Sava wrote a typikon (liturgical office order) for Hilandar, modeled on the typikon of the monastery of The Mother of God Euergetes in Constantinople. Besides Hilandar, Sava was the ktitor (founder, donator) of the hermitage at Karyes (seat of Athos) for the monks who devoted themselves to solitude and prayer. In 1199, he authored the typikon of Karyes. Along with the hermitage, he built the chapel dedicated to Sabbas the Sanctified, whose name he received upon monastic vows.

His father died on February 13, 1199. In 1204, after 13 April, Sava received the rank of archimandrite.

As Nemanja had earlier decided to give the rule to Stefan, and not the eldest, Vukan, in the meantime, back home, the latter began plotting against Stefan; he found an ally in Emeric, the King of Hungary with whom he banished Stefan to Bulgaria, and Vukan usurped the Serbian throne. Stefan returned to Serbia with an army in 1204, and pushed Vukan to Zeta, his hereditary land. After problems at Athos with Latin bishops and Boniface of Montferrat following the Fourth Crusade, Sava returned to Serbia in the winter of 1205–06 or 1206–07, with the remains of his father which he relocated to his father’s endowment, the Studenica monastery, and then reconciled his quarreling brothers. Nemanja (Simeon) was canonized in 1206.

Having spent 14 years in Mount Athos, Sava had extensive theological knowledge and spiritual power.[7] According to Sava’s biography, he was asked to teach the court and people of Serbia the Christian laws and traditions and “in that way enwisen and educate”.[12] Sava then worked on the religious and cultural enlightenment of the Serbian people, educating in Christian morality, love and mercy.[12] While working on the Orthodox enlightenment, he also worked on the church organization.[12] Since his return in 1206, he became the hegumen of Studenica, and as its elder, self-willed entered regulations on the independent status of that monastery in the Studenica Typikon.[8] He used the general chaos in which the Byzantine Empire found itself after the fall of Constantinople (1204) into the hands of the Crusaders, and the strained relations between the Despotate of Epirus (where the Archbishopric of Ohrid was seated, which the Serbian Church was subordinated to) and the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople in Nicaea in his advantage.[13] The Studenica Typikon became a sort of lex specialis, which allowed Studenica to have independent status (“Here, therefore, no one is to have authority, neither bishop nor any one else”) in relation to the Bishopric of Raška and Archbishopric of Ohrid.[13] The canonization of Nemanja and the Studenica Typikon would be the first steps towards the future autocephaly of the Serbian Church and elevation of the Serbian ruler to king ten years later.[14]

Enlightenment

In 1217, archimandrite Sava left Studenica and returned to Mount Athos. His departure has been interpreted by a part of the historians as a revolt against his brother Stefan accepting the royal crown from Rome. Stefan had just prior to this made a large switch in politics, marrying a Venetian noblewoman, and subsequently asked the Pope for a crown and moral support. Stefan’s politics were not well received in the country; Orthodox tradition had already taken grip, especially Sava rose against his brother, to whom he had up until then been a faithful companion; he was the main representative of Orthodoxy and Byzantine ecclesiastical culture in Serbia. Sava had diplomatically helped his brother in obtaining the royal title. It is possible that Sava did not agree with everything in his brother’s international politics, however, his departure for Athos may also be interpreted as a preparation for obtaining the autocephaly (independence) of the Serbian Archbishopric. His departure was planned, both Domentijan and Teodosije, Sava’s biographers, stated that before leaving Studenica he appointed a new hegumen and “put the monastery in good, correct order, and enacted the new church constitution and monastic life order, to be held that way”, after which he left Serbia.

On 15 August 1219, during the feast of the Dormition of the Mother of God, Sava was consecrated by Patriarch Manuel I of Constantinople in Nicaea as the first Archbishop of the autocephalous (independent) Serbian Church. With the support of Emperor Theodore I Laskaris and “the Most Venerable Patriarch and the whole Constantinopolitan assembly” the blessing that the Serbian archbishops receive consecration from their own bishops’ assemblies without visiting the Patriarch of Constantinople. Sava had thus secured the independence of the church, in the time when Serbia was elevated into a kingdom; in the Middle Ages, the church was the supporter and important factor in state sovereignty, and political and national identity.

From Nicaea, Archbishop Sava returned to Mount Athos, where he profusely donated to the monasteries. In Hilandar, he addressed the question of administration: “he taught the hegumen specially how to, in every virtue, show himself as an example to others; and the brothers, once again, he taught how to listen to everything the hegumen said with the fear of God”, as witnessed by Teodosije. From Hilandar, Sava travelled to Thessaloniki, to the monastery of Philokalos, where he stayed for some time as a guest of the Metropolitan of Thessaloniki, Constantine the Mesopotamian, with whom he was a great friend ever since his youth. His stay was of great benefit as he transcribed many works on law needed for his church.

Upon his return to Serbia, he had great engagement regarding the organization of the Serbian church, especially regarding the structure of bishoprics, those that were situated on locales at the sensitive border with the Roman Catholic West. At the assembly in Žiča in 1219, Sava “chose, from his pupils, God-understanding and God-fearing and honorable men, who were able in managing by divine laws and by tradition of the Holy Apostles, and keep the apparitions of the holy God-bearing fathers. And he consecrated them and made them bishops” (Domentijan).

Sava gave the newly appointed bishops law books and sent them to bishoprics in all parts of Serbia. It is not known how many bishoprics he founded. The following bishoprics were under his administration: Zeta (Zetska), seated at Monastery of Holy Archangel Michael in Prevlaka near Kotor; Hum (Humska), seated at Monastery of the Holy Mother of God in Ston; Dabar–Bosna (Dabrobosanska), seated at Monastery of St. Nicholas on the Lim; Moravica (Moravička), seated at Monastery of St. Achillius in the Moravica region; Budimlja (Budimljanska), seated at Monastery of St. George; Toplica (Toplička), seated at Monastery of St. Nicholas in the Toplica region; Hvosno (Hvostanska), seated at Monastery of the Holy Mother of God in the Hvosno region; Žiča (Žička), seated at Žiča, the seat of the Church; Raška (Raške), seated at Monastery of Holy Apostles Peter and Paul in Peć; Lipljan (Lipljanska), seated at Lipljan; Prizren (Prizrenska), seated at Prizren. Among his bishops were Ilarion and Metodije. In the same year Sava published Zakonopravilo (or “St. Sava’s Nomocanon”), the first constitution of Serbia; thus the Serbs acquired both forms of independence: political and religious.

The organization work of Sava was very energetic, and above all, the new organization was given a clear national character. The Greek bishop at Prizren was replaced by a Serbian, his disciple. This was not the only feature of his fighting spirit. The determination of the seats of the newly established bishoprics were also performed with especially state-religious intention. The Archbishopric was seated in Žiča, the new endowment of King Stefan, further north of Ras (the capital) and Studenica, and not far from the Hungarian borders. The bishopric in Dabar on the Lim river was situated towards the border with Bosnia, to act on the Orthodox element there and suppress the Bogomil teaching. The bishopric of Zeta was located on the Prevlaka peninsula, Bay of Kotor, out of real Zeta itself, and the bishopric of Hum in Ston; both of these were almost on the outskirts of the kingdom, obviously with the aim to combat the Catholic action which had spread especially from the Catholic dioceses of Kotor and Dubrovnik.

In earlier times, also Orthodox monasteries were subjected to the supervision of the Catholic Archdiocese of Bar; after Sava’s action that intercourse began to change in the opposite direction. After Sava’s organization, Orthodoxy finally became the state religion of Serbia. Sava, in that respect, worked consistenly and without any regard. The Bogomils had been prohibited already by his father, Nemanja, while Sava, as an Athonite Latinophobe, did his part all to prevent and weaken the influence of Catholicism. Through his clergy, which he directly influenced as an example and with teaching, Sava rose also the general cultural level of the whole people, striving to develop human virtues and a sense of civic duty. The Serbian state thought of the Nemanjić dynasty was created by Nemanja, physically, and intellectually by Sava.

Pilgrimage

After the crowning of his nephew Radoslav, the son of Stefan, Sava left the Serbian maritime in 1229 for a trip to Palestine. He visited almost all the holy places and endowed them with valued gifts. The Patriarch of Jerusalem, Athanasius, along with the rest of the prelates, and especially monks, warmly greeted and welcomed him. On the way back he visited Nicaea and the Byzantine Emperor John Vatatzes, where he remained for several days. From there, he continued his journey to Mount Athos, Hilandar, and then via Thessaloniki to Serbia. After a short stay at Studenica, Sava embarked on a four-year trip, by himself, throughout the lands where he confirmed the theological teaching, and delivered constitutions and customs of monastic life to be kept, as he had seen in Mount Athos, Palestine and Middle East, according to Teodosije. While visiting Mar Saba, he had been gifted the Trojeručica (the “Three-handed Theotokos”), an icon of Nursing Madonna, and the crosier of Sabbas the Sanctified, which he brought to Hilandar.

After the throne change in 1234, when King Radoslav was succeeded by his brother Vladislav, Archbishop Sava began his second trip to the Holy Land. Prior to this, Sava had appointed his loyal pupil Arsenije Sremac as his successor to the throne of the Serbian Archbishopric. Domentijan says that Sava chose Arsenije through his “clairvoyance”, with Teodosije stating further that he was chosen because Sava knew he was “evil-less and more just than others, prequalified in all, always fearing God and carefully keeps His commandments”. This move was wise and deliberate; still in his lifetime he chose himself a worthy successor because he knew that the further fate of the Serbian Church largely depended on the personality of the successor.

Sava began his trip from Budva, then via Brindisi in Italy to Acre. On this road he experienced various bad events, such as an organized pirate attack in the rough Mediterranean Sea, which however ended well. In Acre he stayed in his monastery dedicated to St. George, which he had earlier bought from the Latins, and then from there went to Jerusalem, to the Monastery of St. John the Apostle, “which he, as soon as arriving, redeemed from the Saracens, in his name”. Sava had a prolonged stay in Jerusalem; he was again friendly and brotherly received by Patriarch Athanasius. From Jerusalem he went to Alexandria, where he visited Patriarch Nicholas, with whom he exchanged gifts.

After touring the sanctities in Egypt, he returned to Jerusalem, from where he went to the Sinai, where he spent the Lent. He returned briefly to Jerusalem, then went to Antiochia, and from there across Armenia and the “Turkic lands” he went on the “Syrian Sea” and then returned on a ship to Antiochia. On the ship, Sava became sick, and was unable to eat.

After a longer trip he arrived at Constantinople where he briefly stayed. Sava first wanted to return home via Mount Athos (according to Domentijan), but he instead decided to visit the Bulgarian capital at Trnovo, where he was warmly and friendly admitted by the Bulgarian Emperor Ivan Asen II (father-in-law of King Vladislav) and Bulgarian Patriarch Joakim. As on all his destinations, he gave rich gifts to the churches and monasteries: “[he] gave also to the Bulgarian Patriarchate priestly honourable robes and golden books and candlesticks adorned with precious stones and pearls and other church vessels”, as written by Teodosije.

Sava had after much work and many long trips arrived at Trnovo a tired and sick man. When the sickness took a hold of him and he saw that the end was near, he sent part of his entourage to Serbia with the gifts and everything he had bought with his blessing to give “to his children”. Domentijan accounted that he died between Saturday and Sunday, most likely on 14 January 1235.

Sava was respectfully buried at the Holy Forty Martyrs Church. Sava’s body was returned to Serbia after a series of requests, and was then buried in the Mileševa monastery, built by Vladislav in 1234. According to Teodosije, Archbishop Arsenije told Vladislav “It’s neither nice nor pleasing, before God nor the people, leaving our father [Sava] gifted to us by the Christ. An equal to apostles – who made so many feats and countless efforts for the Serbian lands, decorating it with churches and the kingdom, the archbishopric and bishops, and all constitutions and laws – that his relics lie outside his fatherland and the seat of his church, in a foreign land”.

King Vladislav twice sent delegations to his father-in-law Asen, asking him to let the relics of Sava be transferred to the fatherland, but the Emperor was unappealing. Vladislav then personally visited him and finally got the approval, and brought the relics to Serbia.

With the highest church – and state honours, the relics of Saint Sava were transferred from the Holy Forty Martyrs Church to Mileševa on 6 May 1237. “The King and the Archbishop, with the bishops and hegumens and many noblemen, all together, little and great, carried the Saint in much joy, with psalms and songs”.

Sava was canonized, and his relics were considered miraculous; his cult remained throughout the Middle Ages and the Ottoman occupation.

Burning of St. Sava’s relics

When the Serbs in Banat rose up against the Ottomans in 1594, using the portrait of Saint Sava on their war flags, the Ottomans retaliated by incinerating the relics of St. Sava on the Vračar plateau in Belgrade. Grand Vizier Koca Sinan Pasha, the main commander of the Ottoman army, ordered for the relics to be brought from Mileševa to Belgrade, where he set them on fire on 27 April.

Monk Nićifor of the Fenek monastery wrote that “there was great violence carried out against the clergy and devastation of monasteries”.

The Ottomans sought to symbolically and really, set fire to the Serb determination of freedom, which had become growingly noticeable. The event, however, sparked an increase in rebel activity, until the suppression of the uprising in 1595. It is believed that his left hand was saved; it is currently held at Mileševa.

The Church of Saint Sava was built near the place where his relics were burned. Its construction began in the 1930s and was completed in 2004. It is one of the largest churches in the world.