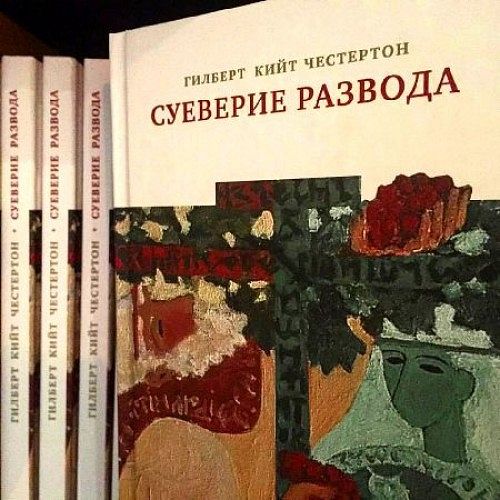

The first Russian edition of the book Superstition of Divorce by the famous British author G. K. Chesteron was presented on September 28 at the “Pokrovskie Vorota” cultural center in Moscow. Among the presenters of the book, dedicated to the topic of Christian marriage, was translator Adam Strock, an American Orthodox Christian who spent five years laboring over the text with a team of helpers. He noted that night that Chesterton wrote about 100 books and countless essays, although less than 10 percent of the books and less than 1 percent of the essays have as yet been translated into Russian.

Adam Strock was raised as a Baptist, spent almost twenty years as a lazy agnostic, in his own words, and came to Orthodoxy at age thirty-eight, nearly fifteen years ago. He discovered Chesterton twelve years ago, and wishes he had much earlier. He has a BA and MA in Russian, language and literature, and a state teaching certificate in English, both for native speakers and English as a foreign language, and has been teaching for twenty-two years. He currently lives in Russia with his wife and four children.

A panel discusses the publication of the Russian translation of The Superstition of Divorce. Adam Strock is seated second from the left. Photo: blagovest-info.ru

A panel discusses the publication of the Russian translation of The Superstition of Divorce. Adam Strock is seated second from the left. Photo: blagovest-info.ru

—Please give us some background on your work—on the topic of the book, and on the process of translating, editing, and getting it into print.

— The Superstition of Divorce was written during and after the First World War when the idea of easy, “no fault” divorce was first proposed and promoted in England, long before that kind of divorce became the general norm in the U.S. Although the title implies a focus on divorce, the book is really about the essence of marriage, and considers it from a practical, philosophical and sociological standpoint, rather than the hundreds of books we can buy dealing with its theological or psychological aspects. In defining the essence of marriage, it helps the reader see how every other modern change in social mores is an attack on the sanctity of marriage, as well as who benefits from such efforts to tear it apart as the foundational institution of society.

It took more than five years to get the translation into print, from start to finish, in part because the translation was a volunteer group project meeting not more than once a month, rather than the work of an individual translator. It took a year and a half to get a complete text in print, and another year and a half to complete the general editing and footnote the large number of references that leave native English speakers scratching their heads, and running to Google and Wikipedia to figure them out in a context that spans far beyond Chesterton’s time (i.e., it is by no means a merely contemporary work). Then it took months to find a publisher, and then for over a year the publisher couldn’t get a distributor—such is the nature of the modern book industry.

The translation was done in what is probably not a common manner: I would assemble a group of Russian Anglophiles (we dealt with the issue of removing anglicisms later), and they would all follow the original text in English, while I (the one that fully understood the original) would read a “dirty translation” in my less-than-perfect Russian. Then the group would correct my inaccuracies and ponder how to better express the ideas in good Russian. Idioms and colloquial references presented a special challenge, but having a number of people on hand dramatically improved the likelihood of thinking of good Russian equivalents. My chief concern was ensuring the preservation of all of Chesterton’s thought, and where possible, great humor. Even so, a few things were lost.

—How did you first get acquainted with Chesterton, and what about him really drew you?

—I found Chesterton through C.S. Lewis, unsurprisingly when I was forty. Lewis had been my co-pilot in guiding me back to faith, which I had once had as a child and young adult. But I had already immigrated to Russia, and it was friends in Moscow who loaned me the first books that I read. At first, he was a difficult read: I was not used to having to think so much as I read, and slowly grasping and connecting ideas. But somewhere in the fourth book, I “got his drift,” and a tremendous vista opened up before me that left me simply in jaw-dropping awe.

I would say that he is a complete university in the person of one man. Just a man, with his errors and imperfections, but I learned that most criticism of him was made by people who had only read one or two of the nearly hundred books that he wrote, that never grasped that he was a bona fide genius, the kind we see only once or twice in a millennium. In a sense, I can’t even tell you about it—as with Einstein, you would have to see for yourself, extensively, to grasp that that is true. One can only offer fragments of the deep thought that makes him the opposite of a creature of his own time. For example, in The Superstition of Divorce, when he says, talking about the idea of natural selection, “To talk of the purpose of Nature is to make a vain attempt to avoid being anthropomorphic, merely by being feminist. It is believing in a goddess because you are too skeptical to believe in a god.”

He points up an Achilles’ heel of Darwinian thought—the danger of attributing personal qualities to impersonal forces. And you have to read that, three or four times, and think about it. It is unexpected. It is succinct. It is true. And yet hardly anybody realizes the truth of it until they have read this and thought about it.

—How has your life personally changed due to Chesterton’s influence?

—Chesterton, with Lewis, serves as a gatekeeper in my life. They make it clear that, if faith is difficult at times, the alternatives are simply insane. They keep me going to church, Confession and the Eucharist, even when I am tired of repenting and struggling. They illuminate the words of the Apostle Peter, Where can we go, Lord? You have the words of eternal life (Jn. 6:68). They have both, but especially Chesterton, energized how I view marriage and helped make it possible to see how I can strive to return to and fulfill the ideal we are called to, and that however badly I do it, it is better to do that than to quit when the going gets rough. GKC, as he is called for short by his admirers, has helped restore my faith in the child’s view I once had, to return to that child’s idealism, to lift up that sword as the boy I once was did and to vow to be a faithful husband and father, that my children might never experience what I and so many have experienced—the divorce of one’s parents or one’s own divorce.

—Can you give us a taste of how he does this in the book?

Not really. It is the connection of all the ideas, of seeing how the breakup of the family produces slavery, just as its primal affirmation in the binding of one man to one woman produces freedom, by seeing the whole picture produced, that this might be seen. I might add that as someone who grew up on Tolkien, the necessity of desiring the ideal expressed imaginatively in JRR's works (such as Beren and Luthien) is clearer to me, as is the fact that our chief sin is in holding the ideal as "sour grapes", as something unattainable, and so not to desired or expected.

—How does Chesterton fit into Orthodox theology and praxis? Are there comparable writers in the Orthodox Tradition that you can point to?

—I don’t think Chesterton can be compared to anybody. He is unique. I have made comparisons of him to Pushkin in terms of his importance to English literature, and have asked what a Russian who knows and values Pushkin would do in a Russia where people had never heard of him. They would be viewed as oddballs, going on about some “great” Russian writer they had never heard of (I proposed a translated form, “Cannonson”, to achieve the effect of unfamiliarity that the name of Chesterton actually produces). People ask, understandably, “If this guy is so important, why haven’t we heard of him?” There are good answers, not the least of which is an education system controlled by the enemies of the Faith that hate him, what he stands for, and that he shows up their ideas as nonsense, and because he deals with their ideas thoroughly, they have no good response—only insults or silence. So he has been excluded from our literature programs.

—But, Chesterton, in the end, was not Orthodox. What were his faults, drawbacks, or shortcomings that people should be aware of?

—GKC was not Orthodox. He came to faith first in the Anglican Church, and later, having become sure that the Anglican Church had lost its way, made his way to the Roman Catholic Church. He sought the ancient Church, and knew nothing of the Orthodox Church. His historical sources treated the Orthodox Church as having fallen with Constantinople. And in the reading of all heterodox writers, we must be careful regarding how their formal beliefs affected their worldview, and in what ways that worldview departs from Orthodox teaching. But paradoxically, many writers, thinkers and teachers that are formally Orthodox have also departed from Patristic thinking; being a formal member of the Orthodox Church is no guarantee that one is speaking Orthodox truth, and not being one is no guarantee of the converse.

Chesterton does not deal with Roman Catholic theology as such. Most of his writings were aimed at large audiences consisting of non- and anti-Catholics. But what he does say generally coincides with our ancient teachings and what the Church Fathers said and held, and other than generally supporting the Pope and the authority of the Catholic Church, he nowhere defends doctrines contrary to the teachings of the Orthodox Church. We can take Church teaching that tells us how we ought to live, and put Chesterton next to that teaching, explaining how and why it is true. For a concrete example, I would suggest reading the Russian Orthodox Church’s document from 2000 “Bases of the Social Conception of the Orthodox Church” and putting GK’s What’s Wrong With the World right beside it. The latter illuminates the former, showing in “secular” terms why the Church is right.

—Why did you choose this particular book?

—I chose this book because of the large number of divorces happening under my nose, both in the Church and out of it, among friends, neighbors, and fellow parishioners, some of whose children I have taught or still teach. I work with those kids, and can see that they do worse across the board than other kids, even kids from non-Christian families who have reasonably healthy marriages. They are constantly distracted, do their homework poorly, or don’t do it at all, and do poorly or outright fail on tests.

My sister in the U.S. got divorced, and friends of ours here got divorced at about the same time, and of the two, I was more shaken by that of our friends; it showed me clearly that their divorce impacted me, even though I was on the outer rim, so to speak—not near the epicenter. It made me realize that marriage and divorce are not private affairs, affecting only the couple involved, or even their children. All kinds of relationships are damaged or flat-out broken, starting with the immediate family, proceeding to in-laws, then to friends and neighbors, finally to other relationships, like teachers or colleagues. One’s divorce really is everybody’s business, insofar as they are affected. And for me alone, the result is a friendship snuffed a-borning1, seeing an erstwhile friend for ten seconds and shaking hands in passing once or twice a year, instead of what could have been.

Something is really missing in the Church today, and I think it is because even though we have all of the right and necessary teachings, we don’t avail ourselves of them, because we think we already know what we need to know. We come into the Church with our own ideas and baggage of the world—worldly ideas about what marriage and divorce are, and assume them to be right, and never really inquire as to what the Fathers taught. Oh sure, maybe parishioners read a pious book or two on the topic, but sometimes those books don’t even reference the Fathers, but rather modern psychology, statistics and studies; that is, more of what the world teaches, and little to nothing about what the Christian ideal really is; that we ought to desire to attain that ideal, and that it is both possible and realistic to do so, especially when both spouses are trying to live the life of the Church. I don’t think you would find a single Father who approves of divorce in such cases, and yet most would name dozens of situations—and I am not talking about unrepentant adultery—in which they think divorce an acceptable solution for two people who are both trying to engage in lives of repentance in the Church.

Chesterton does an end-run around all of that. He asks what marriage has been, both for Christians and non-Christians throughout history. And surprisingly, for those that seek to excuse divorce as a ready option, he does not propose imposing faithfulness in marriage by force of law, secular or ecclesial, but by helping us understand what the thing is, and what we ought to desire, as well as what happens when we abandon that ideal, treating it as impossible to obtain. He discusses what the family is, and what the vow is, and I would express it in terms of Let your yes be yes, and your no be no (Mt. 5:37)—twenty years down the road, extending that “yes” over time, so that tomorrow it is still “yes,” and to the end of our days. And what he says can be accepted by everyone we know, believer or not. The “secular route” allows him to speak to everyone about things they can’t really deny. And there are those who would deny. Both individuals who want the “freedom” to do whatever they want, even if it is destructive (and they will deny or belittle the destruction), and forces of big business and government, and the powers behind them, who want ever-cheaper labor and to whom the family as a united thing is an obstacle to increased profits from and power over the people. The family is the one thing that commands an older and higher loyalty than that due to an employer or to the State. Break down the family, and the individual is helpless before the State. Marriage, held as a sacred thing, is a mainline defense against tyranny, and we have seen its sanctity destroyed.

—Why do you think this book was needed in Russian? How much of an audience for it do you think there is or will be?

—I think this book is needed in Russian, and in English, because the Russians, like everyone else, are experiencing this social calamity of mass divorce, with divorce rates approaching fifty percent. The bad and poorly thought-out ideas fueling it—that marriage is a vehicle for personal happiness, and if that is lacking, then divorce is justified—have spread around what was once the civilized world. I think the audience will be limited first of all because fewer and fewer people are reading books, and fewer have patience with anything that requires more than a single chapter to fully examine a complex idea. We want short, quick, and practical answers, even if the practice stems from bad theory, because we have come to think theory; and the ideal of things, to be unimportant or unattainable. Plus, it is hard to express an idea when people think they already know all they need to know.

But I think the older generation of Russian readers, who at least grew up with a strong tradition of reading, will find it challenging and the style unexpected or unusual, but understandable. And sometimes young people can surprise you! There are some really bright young people out there. At the summer camp I have been working at, a young man of only seventeen has already read GKC’s Orthodoxy and The Everlasting Man, grasps it, and is eager for more. So I think this might contribute to a real growth of interest in the relevance of Chesterton to Russia, as the problems of the West, springing from the ideas of the West, become Russia’s problems. The modern Russian no longer understands Tatyana Larina from Evgeny Onegin when she says “Я другому отдана и буду век ему верна” (“Ya drugomu otdana I budu vek emu verna”) This book can help restore that understanding.

—Could you please unpack that a bit, including a translation of that phrase.

—The translation is: “I have been given to another, and I will be faithful to him all my life.” What we have lost, as a culture, is the ability to understand Tatyana, or anyone who proposes being faithful to one's wedding vows when one wishes one could break them. The modern man, who has been brought up in a culture in which divorce has been normalized, says, “Why stay with that old general she doesn't have feelings for? Why doesn't she just run off with Onegin?” We have lost the ability to grasp that one can and should take one's word seriously, especially a sacred vow. The modern man does not see that civilization stands or falls on the ability of people to keep their word and do what they promised, and not merely what they feel like in the moment.

—What particular problems did you have in translating this book? Odd or outdated turns of phrase, hard to translate metaphors, symbolism, and so on?

—As to problems in translation, there were some things, like humor, of a serious idea wrapped up in a funny turn of expression, that had to be footnoted, or were just plain lost. One great example that I could not save (though I fought to do so) was from these lines towards the end of the book: “The point of divorce reform, it cannot be too often repeated, is that the rascal should not only be regarded as romantic, but regarded as respectable. He is not to sow his wild oats and settle down; he is merely to settle down to sowing his wild oats. They are to be regarded as tame and inoffensive oats; almost, if one may say so, as Quaker oats.”

The humor changes the tone of the writing, and shows a man capable of maintaining a sense of humor even in such serious thought. The connection between the euphemism for fornication (sowing wild oats), Quaker pacifism, and oatmeal is really funny, and gives a picture of a man with a balanced mind. But Russian doesn't have that euphemism. Russians hardly know who the Quakers were, and have never seen the breakfast cereal, which, ironically, already existed and was well-known in Chesterton's time. So the editor found a Russian idiom (“наломать дрова,” “nalomat drova”) which speaks of the general mistakes of youth, but is not specific to fornication and drops the humor altogether.

Also, there were a few obscure references; a couple I was able to get help on, and one which we are left to speculate on the meaning of (a reference to a crusade in Russia).

—You wrote on Facebook that people have seen you as eccentric or kooky for your love of Chesterton. What core message is it that you believe Chesterton has for our modern world that makes you persevere through this opposition and through any snags you had along the way in getting the book into publication?

—Like I said, Chesterton keeps me pointed toward the Church. Plus, he has taught me invaluable tools of thinking, how to see history, politics, literature, and the rest, which really enlightens and explains, which always takes into account the opposing ideas, and strives for appreciation of one’s opponent. He loved his enemies, and so, in his lifetime, didn’t have any; he converted them (the ones that didn’t retreat into insults or silence) into his friends. He never thought much of himself; he cared about both the ideas he spoke of, and the people he was speaking them to. He was generous to a fault (he drove his wife crazy at times), and lived a life that I can only describe as saintly. He had his lapses, and what I believe to be his mistakes, but he is the kind of man I would like to be: fully engaging both his mind in thinking, and dealing with disagreement and challenge, and his heart in loving his neighbor.

—Which is, of course, something to which the Lord has called each and every one of us. Thank you very much for taking your time to speak with us!