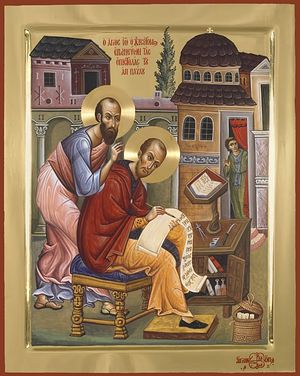

St. John Chrysostom writiing his exegesis on the epistles of the Apostle Paul.

St. John Chrysostom writiing his exegesis on the epistles of the Apostle Paul.

Let us imagine a workday in the world of St. John Chrysostom, who wrote more books than ten men could have done, and gave such exegetical writings as require an eternity to fathom. Imagine a world without a single mechanical noise, no cars, light bulbs, where no more than a lonely little oil lamp shines through the deep nocturnal darkness, hanging above the massive Scriptures sewn from sheep skin, or the hooves of horses lightly clopping against the stone walkway. A world without television, internet, mobile phones, or Facebook; without trains, or honking horns; a world where the grind of automated material is never heard. It is a wireless world—that is, without networks—without beeps, without electrical luminescence, but filled with grace, the buzzing of bees, and the shining of stars. It is a world without airplanes in the sky, but filled with birds.

The day begins early but without alarm clocks, only the crowing of roosters. It is a world with Divine Liturgy and unhurried, soothing chants, without microphones or speakers, but with voices from man’s breast, filled with strong, elevated singing. I remember how on Mt. Athos Elder Dionysios of Colciu[1] told me in a whisper that when the great Nectarios the proto-psalm-singer sang, a strong flow of air, or wind, filled with melodious Byzantine harmony would form in front of him and would even resurrect the relics of the dead on the Holy Mountain.

But let us return to the days of St. John Chrysostom. After the heavenly Communion of the Body and Blood of Christ, several thousand hungry people crowding around the church would unhurriedly treat themselves to the generous alms gathered through the sermons of the great Antiochian.

The day then continues with the study of books, long periods of writing, exegesis, letters to various corners of the empire that would be sent today and received a year later, then hierarchical instructions, talks with priests of the diocese, long, long prayer, reading the daily cycle of services, prayer rule, then nighttime reading by the light of the oil lamp and finally sleep on a bench or wooden planks.

In those days, people did not live in separate rooms. There was one large room for everyone that served as a guest room, a dining room, a kitchen, and a bedroom, so that everything was shared in a brotherly manner from the bowl of food to the crying of infants in the middle of the night. A monk, however, had his own cell, filled with the light of prayer and humility.

What I am talking about can of course be experienced to a very small degree if you go to a solitary monastery and immerse yourself for a time in its mystery of prayer and peace. But then you have to return to the commotion of the city. That is how it was for me. Two months of summer vacation spent on the Holy Mountain were coming to their inescapable end, and I was forced to return to the roads of the world: from Karyes to Daphne, Uranopolis and Thessaloniki. The city seemed horribly noisy to me, although compared to other cities it is rather quiet. I was everywhere besieged by an acute sense of the meaningless talk, and loneliness, announced to all by loud outbursts. People wailed their non-existence; they gesticulated in the streets and clattered uselessly. My ears hurt from the noise, and until I got used to it a migraine headache did not leave me alone.

Do you see what a colossal difference there is between these styles of life, what a gulf there is fixed between our way of living and that of the holy fathers?! What clamor there is here over trifles in the 21st century, how the earth wails, extinguished of its strength, how much exhausting uselessness there is, splashing from the screen into the hearts of people keeping up an appearance of existing.

The noise of a welder, a jackhammer or a chain saw, the clatter of train wheels, running motors—it is all no more than the futile wail of matter overburdened by the weight of human sin, ashamed of man’s tiresome desire for exhilaration without a cause.

Deciding to return to authentic existence does not mean short-circuiting all of man’s technology. It means beginning to listen attentively to the voice of the earth, more deeply experiencing the mystery of life, returning to the villages (as St. Paisios of the Holy Mountain advised), learning the ancient customs that build a foundation for the soul, putting our effort into the church and more deeply seeing this wonder of life that God unceasingly pours out upon us, to sense His boundless love.