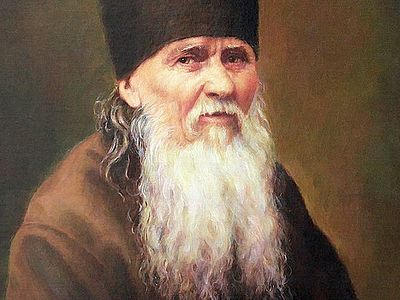

In the history of Russia, as in world history, there are saints who serve as “milestones,’ as it were, on the road to the Most High. One such righteous one was St. Ambrose of Optina, whose memory is celebrated on October10/23.

The future great starets—or elder—of Optina, Hieromonk Ambrose, was born on December 4, 1812, in the town of Great Lipovitsa in the Tambov gubernia1, into the large family of Michael Feodorovich Grenkov, a sexton, and his wife, Martha Nikolaevna. At twelve years of age his parents enrolled him in the Tambov Spiritual School, and after graduating in 1830, he entered the Tambov Spiritual Seminary. His studies were successfully completed in six years2, but Alexander did not enter the Spiritual Academy, nor did he become a priest. For a while he was a tutor in the family of a certain landowner, and afterwards an instructor at the Lipetsk Spiritual School.

At the age of twenty-seven, tormented by pangs of conscience over the promise he had given to God in the last class of seminary—to be tonsured a monk if he recovered from his serious illness—Alexander Mikhailovich secretly, not even asking permission from the diocesan authorities, fled to Optina Hermitage, which at that time was a “fiery pillar in the gloom of the surrounding night, which attracted all who were in any way seeking the light.”

By tradition, this monastery—three versts (about two miles) from the town of Kozel’sk, surrounded on three sides by impenetrable virgin forests, and on the fourth—the River Zhizdra—was founded by a repentant robber named Opta, a comrade-in-arms of the Ataman Kudeyar.3 At the foundation of the life of this monastery was the strict keeping of three rules: a strict monastic life, preserving [vows of] poverty, and the striving to always and in everything to do things in the truth, in the complete absence of respect of persons. Those who lived there were great strugglers of piety and great men of prayer, who prayed for Orthodox Russia. Alexander Mikhailovich arrived there, one may say, at the very flower of Optina’s monasticism—when such great pillars as Abbot Moses, and the Elders Leo and Macarius were alive.

In April of 1840, roughly a year after he arrived at Optina, Alexander Mikhailovich Grenkov became a monk. He actively joined in in the everyday life of the monastery: he brewed yeast, baked rolls, and was a cook’s helper for a whole year. After two years he was tonsured into the mantia4 and given the name Ambrose. In 1845, after five years of life at Optina Monastery, the 33-year-old Ambrose had already become a hieromonk.

His health deteriorated markedly in these years and in 1846 he was forced to retire, as he was incapable of fulfilling his obediences, placed on the list of people who were supported by the monastery. Soon the status of his health became so serious that they awaited his death, and according to old Russian custom, Fr. Ambrose was tonsured into the schema. But inscrutable are the ways of the Lord: in two years—unexpectedly for many—the patient began to get better. As he himself said later: “In a monastery, the sick do not die soon, as long as the sickness brings them real benefit.”

It was not only by bodily infirmities that the Lord trained the spirit of the future great starets5. Especially important was his association with the elders Leo and Macarius, who, foreseeing in Ambrose God’s chosen vessel, spoke of him in no other way than: “Ambrose will be a great person.” While listening to the wise counsels of Elder Leo, he was at the same time very attached to Elder Macarius. He often conversed with him, opening his soul to him and receiving advice that was important to him, and he helped him in the work of publishing spiritual books. The young ascetic had at last found what his soul had long thirsted for. He wrote to his friends about the spiritual happiness that opened up for him at Optina Hermitage.

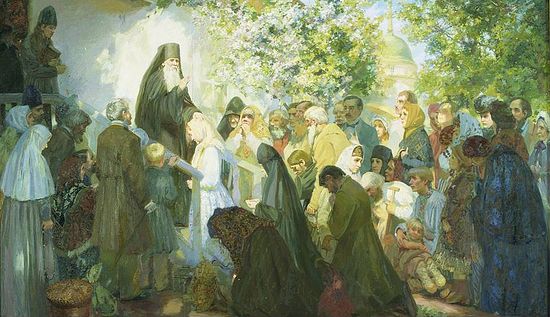

“Just as all roads leading to the top of a mountain come together at the peak, so also at Optina—that spiritual peak—the lofty spiritual podvig6 of interior “activity” came together with serving the world in all the fullness of both its spiritual and worldly needs.” People came to the elders for comfort, healing and advice… People who had become entangled in their worldly circumstances or philosophical quests came to the elders, and it was to Optina that those thirsting for the highest spiritual truth rushed—each person quenched his thirst in this “spring of living water.” The prominent thinkers of the time, philosophers and writers came there more than once or twice: Gogol’, Alexei and Lev Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Vladimir Soloviev, Constantine Leontiev… it is impossible to count them all. For a Russian, a starets is a man sent by God Himself. In the words of F.M. Dostoevsky, “For a Russian soul, wearied by work and grief—and most importantly, by constant injustice and constant sin, both his own and that of the world, there is no stronger need or comfort than to find a shrine or a saint, to fall down before him and to make a bow to him. If we have sin, falsehood, or temptation, nevertheless there is on earth there, somewhere, a holy and high one—he, on the contrary, has the truth. That means that the truth does not die on earth, and consequently, it means that it will come to us, too, someday, and reign over all the earth, as promised.”7

It was Ambrose, by God’s Providence, who was destined to become one of the links in the line of the fourteen Elders of Optina: he took Elder Macarius’ place after the latter’s death, and for the course of 30 years tended to the spiritual needs of suffering souls.

Starets Ambrose appeared at Optina Hermitage and riveted the attention of exclusively intellectual circles just at the time when this intelligentsia was gripped by Western philosophical thought. Himself once the soul of society, having loved everything worldly (he sang and danced well), for whom a “monastery was synonymous with the grave,” he understood better than anyone the intelligentsia’s spiritual search, and by his own life witnessed to the fact that the way that he had chosen was the ideal of that happiness for which everyone must strive.

True are the words: God’s strength is made perfect in weakness (2 Cor. 12:9 KJV). In spite of his physical sufferings, which kept him bedridden almost all of the time, Elder Ambrose, who by this time already possessed a whole range of spiritual gifts—clairvoyance, healing, the gift of spiritual exhortation, and others—received crowds of people every day and answered dozens of letters. Such a gigantic labor could not be accomplished by human strength—here life-giving Divine grace was manifestly present.

Among Elder Ambrose’s spiritual grace-filled gifts, which attracted many thousands of people to him, we ought to mention first of all his clairvoyance: he deeply penetrated the soul of the person talking with him and read it like an open book, not needing the person’s admissions. But charity was simply his requirement: Elder Ambrose generously distributed alms and showed personal concerned for widows, orphans, the sick and the suffering.

In the last years of the elder’s life, with his blessing, the women’s Hermitage of the Kazan Icon was built 12 versts8 from Optina Hermitage, in the village of Shamordino. The order and harmony of the convent were all established by Elder Ambrose himself, and he tonsured many of the convent’s sisters into monasticism with his own hands. By the end of the 1890’s, the number of nuns in the convent had reached 1000, for it had an orphanage, a school, an almshouse, and a hospital.

It was at Shamordino that Elder Ambrose was destined to meet the hour of his death: in October, 1891, in the seventy-ninth year of his life.

Morals and Aphorisms of Elder Ambrose:

-

We should live as a wheel turns—hardly touching the earth at one little point, while all the rest is always reaching upward.

-

Why are people bad? Because they forget that God is over them!

-

If you do something good, you should do it only for God, and so you shouldn’t pay any attention when people are ungrateful.

-

The truth is tough, but it’s God’s beloved.

-

To live, don’t grieve, don’t criticize, don’t irritate anyone, and to all—my regards.

-

Whoever reproaches us gives us a gift, but whoever praises us, robs us.

-

One must unhypocritically live, and to all an example give; then will our work be sure, otherwise it will turn out poor.9

-

Hypocrisy is worse than unbelief.

-

You are not humbling10 yourself, and because of this you don’t have any peace.

-

Our self-love is the root of all evil.