Source: The Guardian

December 14, 2016

When Bucharest faced a radical redesign in the 1980s under communist dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu, engineers moved complete buildings hundreds of metres on metal tracks to preserve the Romanian capital’s architectural heritage.

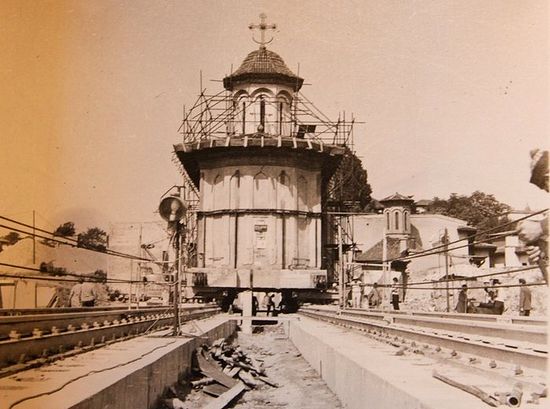

The Schitul Maicilor church in Romania, one of 13 churches that were moved on rails. Photograph: Courtesy of Eugeniu Iordăchescu

The Schitul Maicilor church in Romania, one of 13 churches that were moved on rails. Photograph: Courtesy of Eugeniu Iordăchescu

It must be startling to look out of your window and see a centuries-old church rolling by. Even more so if you are in communist Romania in the 1980s, where news is state-controlled and everyday items rationed. And yet, between 1982 and 1988 almost a dozen churches, as well as other buildings, were moved hundreds of metres in order to save them from destruction, as dictator Nicolae Ceaușescuwent about radically redesigning the heart of Bucharest, the Romanian capital.

That a communist country would go out of its way to save churches is strange enough, but the method of saving them, when other countries would probably have tried to dismantle the buildings and reassemble them elsewhere, makes the achievement all the more impressive.

“We were awestruck at those operations, comparing them with the landing on the moon for a country like Romania,” says Valentin Mandache, an architectural historian who witnessed the moving of several of the churches when he was still a young student.

At the centre of it all was Eugeniu Iordăchescu, a civil engineer who had the radical idea to place whole buildings on the equivalent of railway tracks and roll them to safety.

“I was in the area that was to be knocked down and I saw a beautiful small church and started wondering how it was possible to demolish such a jewel,” says the sprightly 87-year-old, sitting in his dining room in a nondescript apartment in Bucharest, a few miles from where the churches he saved three decades ago still stand. “I thought about the idea of moving it.”

At that time 30,000 residents were being forced from their homes, with an entire district of historical Bucharest, roughly 9,000 houses as well as churches, synagogues and other buildings demolished to make way for Ceaușescu’s grandiose vanity project, the Palace of the People and surrounding civic centre. The remodelled city centre and palace – which still dominates the skyline and is said to be the second largest administrative building in the world after the Pentagon – were supposedly inspired by Ceaușescu’s visit to Pyongyang, the North Korean capital.

Iordăchescu, who worked at engineering and design centre the Project Institute in Bucharest, says that when he first broached the subject of moving the church with his colleagues he was told that it wasn’t possible, that the building would fall over. Some thought he was crazy for even suggesting it, but slowly the idea formed in his head.

The engineer says he reached the breakthrough after seeing a waiter pass through a crowd of people with a tray of glasses in his hand. “I saw that the secret of the glasses not falling was the tray, so I started trying to work out how to apply a tray to the building.”

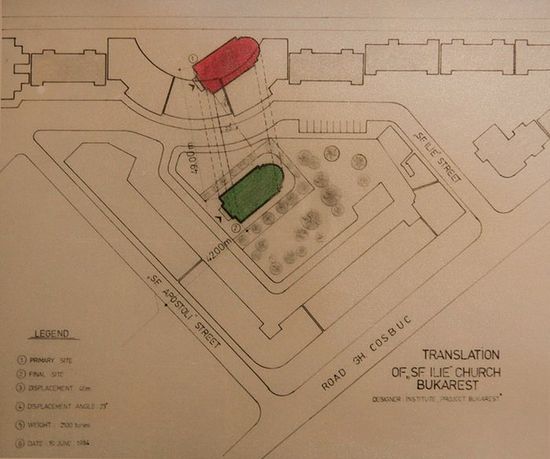

Ultimately a process was developed whereby the ground was dug out from under the churches, with a large reinforced concrete support created and the foundations severed. Tracks were laid, and hydraulic levers and industrial pulleys were used to slowly move the buildings to their new locations, often at a few metres an hour.

One church would require a team of around five engineers for the planning phases, and then upwards of 20 workers when the physical work was under way.

They had to rely exclusively on local equipment and technologies, since communist Romania was largely cut off from the outside world. Tracks and other equipment were reused from site to site to save on costs and materials. Meanwhile, the route from one site to the other had to be cleared and the logistics of the move planned, including issues of gradients and rotating the buildings.

Many were sceptical that it would work, and for the first church they were only given verbal permission to go ahead, with no one wanting to sign the written approval.

The first church to be moved, the 18th-century Schitul Maicilor, weighing 745 tonnes, was relocated 245 metres away from its original site in 1982. The whole project took five months – though the actual process of moving the structures would often take just a few days.

Priests, government officials and locals would often gather to watch the final spectacle; in some photographs Iordăchescu is seen standing alongside the patriarch of the Romanian Orthodox Church.

As time went on the team got more and more ambitious, with the 16th-century Mihai Voda Church being moved in tandem with its standalone tower. The largest church that was moved, technically a monastery, weighed 9,000 tonnes. It was shifted 24 metres from its original location.

In Bucharest and other cities, Iordăchescu and his colleagues moved a hospital and a bank – and even entire apartment buildings, often with the water and gas lines still attached and the people still inside them. “One building, people inside thought the move would start at 9am so they prepared their luggage, with their papers, valuables, but we started at 6am, so at 9am when they went to leave it had already moved a couple of metres,” says Iordăchescu, showing me an old photograph of himself standing on the balcony of a moving building.

Despite the complexity of the work, all of the buildings made it unscathed to their final locations. However, it wasn’t all good news. Iordăchescu has a list of 22 churches that were destroyed in the period, some having already been given permission to be moved, with Ceaușescu impatient to get on with the urban overhaul of the capital.

The Mihai Vodă Monastery was moved and placed behind Soviet-style apartment blocks. Photograph: Courtesy of Eugeniu Iordăchescu

The Mihai Vodă Monastery was moved and placed behind Soviet-style apartment blocks. Photograph: Courtesy of Eugeniu Iordăchescu

Pointing to an image of a church, once located in what is now Piața Unirii – a huge brash square that’s effectively a roundabout a few hundred metres from the Palace of the People – Iordăchescu’s son Adrian, also a civil engineer, says: “It was a tragedy. The priest died of a heart attack. Even the workers didn’t want to demolish it, so Ceaușescu got people from prison to do it.”

Adrian, 54, has continued his father’s legacy, using an updated version of the technology to recently retrofit the city’s Arcul de Triumf monument.

Many of the moved churches, though, ended up being relocated in the shadows of large, soviet-style apartment blocks, often sandwiched tightly as if daring those who pass by to blink and miss them. Visitors to the city can find Schitul Maicilor hidden behind a huge building that contains several government ministries.

Yet, preserving these important churches in the capital, along with their hundreds of years of history, ornate interiors and elaborate iconography and paintings, has had an important cultural legacy.

“It is amazing what they were able to achieve,” says Adrian, adding: “During the moves all the day he was on site, because at the very beginning he heard people from the working team would try to sabotage it, so he would stay 24 hours a day.”

Highlighting Antim Monastery, one of the saved buildings, Mandache points to the importance of what was achieved in saving those buildings three decades ago. “Antim is a jewel of Brancovan-style architecture. Architecture is the most visible identity marker of a community, and those churches are among the most important such markers,” he adds.

The relocation of churches and other buildings stopped with the Romanian revolution in 1989, and in the years since Iordăchescu has received a number of honorary diplomas for his work, as well as a medal from the Romanian Orthodox church. He only fully retired a few years ago.

Yet, as the years go by his achievements have become more and more clouded in the fog of time. “I’m 54, the younger generation of architects don’t know the method,” says Adrian Iordăchescu. “My son is 23 and a student at the architectural university. He’s only really discovering what his grandfather did in the last year or so.”

Still, Iordăchescu is very proud of what he and his colleagues did. “When I see the churches today I still can’t believe it,” he says.