[Go to Part 1]

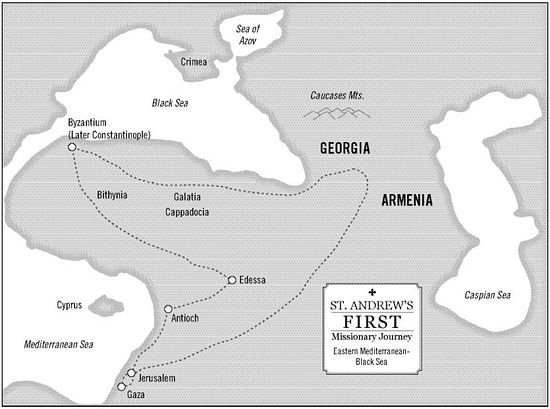

THE FIRST MISSIONARY JOURNEY:

Judea to Constantinople, Pontus, and the Caucasus

RTE: Can you trace St. Andrew’s routes for us?

GEORGE: Yes, according to local tradition, St. Andrew first preached in Judea to the Samaritans and in Gaza, which at the time of Christ was inhabited by Greek Philistines. If you compare the Masoretic text to the Septuagint, the word “Philistine” is translated as “Greek.” This is clear and it is acknowledged by historians.

After Gaza, he went to Lydda in Palestine, where St. George would later be martyred, to Antioch, and then to Ankara and Edessa, today’s Urfa in Turkey, which was an important center for the first Christians. Abgar, King of Edessa, became a Christian and this is where the icon of the Lord, “Made-Without-Hands” is from. According to the sources, this may have been the first Christian kingdom on earth, perhaps as early as 35 or 36 A.D. just a few years after the Crucifixion. After Edessa, some traditions say that St. Andrew went to the Greek town of Byzantium (later Constantinople) in 36 A.D. and appointed the first bishop, St. Stachys,[1] who was one of the seventy disciples of the Lord. Then he preached in Bythinia, Cappadocia and Galatia, up through Greek Pontus, which today is northern Turkey. Then traditions say he turned to Georgia, Armenia and the Caucuses. This was the first trip, after which he returned to Jerusalem.

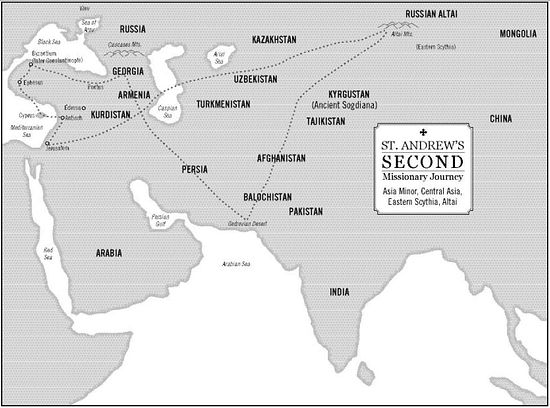

THE SECOND MISSIONARY JOURNEY:

Jerusalem to Central Asia

The second trip was quite different. He followed the same route from Jerusalem, but after Antioch he took a ship to Ephesus to meet St. John. On the way he touched on Cyprus for a few days, at the Cape of St. Andrew. I’m not sure if he met any Cypriotes, it was only a stopping point for the ship. According to Cypriot tradition, because the crew and passengers needed fresh water and this was a desert place, he went ashore and prayed until water poured forth from a rock.

After Ephesus, he went to Antioch, then to Nicea where he stayed for some time. From there he went to Pontus again, and to Georgia. From Georgia, several traditions say that he passed down to Parthia (Persia) through Kurdistan, and then further to the Cynocefaloi in the desert of Gedrozia (now Balochistan) near the coast and the present Pakistan-Iranian border.

RTE: Who were the Cynocefaloi?

GEORGE: This is an extremely interesting subject as these people are mentioned in many early texts. Cynocefaloi translates literally as “the dog-head people.” They are also spoken of in the Life of Saint Makarios, which locates the tribe in a desert far beyond Syria. Tzetzis, a Byzantine historical commentator, refers to them as inhabitants of India, of which modern Pakistan would have been a part. In the Greek Life of St. Christopher (who some speculate came from this area), it is said that that he came to the Roman world passing through the Persian desert, and Marco Polo mentions them as inhabitants of the Indian Ocean. So they could be the same primitive tribes that Alexander the Greek found on his way to the sea coast of the Gedrosian Desert (modern Makran in Pakistan).

Our main source for the Cynocefaloi is Ktesias (5th century B.C.), a well- known ancient geographer, pharmacist and historian from Knidos, whose writings were taken seriously by Byzantine Church fathers, for example by Patriarch Photius the Great (see his Myriobiblos). In Ktesias’ book “Indica,” which St. Photius himself used, there is a whole text dedicated to the Cynocefaloi, “an Indian tribe.” These ancient folk tales (Ethiopian, Slavic, Persian, Arabic, Armenian, Greek, etc.) all refer to the dramatic contact of Alexander the Great and the Cynocefaloi.

RTE: This also explains why I’ve seen many old Greek icons of St. Christopher with a dog’s head. At first I was shocked, it seemed like blasphemy and I wondered what on earth the Greeks were thinking. No one was able to explain it, except that St. Christopher’s life from the Menaion says that he was so tremendously ferocious-looking that when Emperor Decius saw him, he fell off his throne from fright. Do you think there was a connection?

GEORGE: Exactly. The sources say that St. Christopher came across the Persian Desert. These people lived on the other side of the desert.

I have my own theory, although this explanation is not in the old texts that cite these people, because the sources assume the reader is already familiar with the place names and locations. Several sources say that St. Andrew was in this northeast region of Pakistan, and we know that there were peoples in this area who slashed their cheeks from mouth to ear, so that all the teeth showed. Marco Polo saw this tribe, whom he called the Cynocefaloi. He said that they looked like mastiffs; that is, they didn’t have elongated heads like German shepherds with the long nose, but like mastiffs. You can imagine – a mastiff has a round, flat face shaped more like that of a human. They cut the cheeks, filed the teeth, cropped the ears, and reshaped the skulls of their babies so that they would grow into a very ferocious aspect. All of this was to protect themselves from the constant invasions of the area.

If you go to some sub-Saharan tribes today along the Nile in Rwanda, or along the Amazon, or in New Guinea, the faces of some tribal peoples can frighten you terribly. They systematically mold their faces into something ferocious – the shape of the head, cheeks, teeth…. These people were ferocious in looks, but not ferocious in their ways. They were simply a primitive people who needed to protect themselves

According to the Syriac text, when St. Andrew went to these people they were transformed into normal human beings. In my opinion this means that after their baptism they simply stopped doing these things. In Deuteronomy it is forbidden to scar or mutilate the face, so this would have been part of the apostolic heritage that St. Andrew taught to this people.

The Syriac sources say that when St. Andrew first saw them he was horrified. He panicked and fled back to the shore to jump into the boat, but as he reached the shore he smelled incense and realized that the Lord Himself had guided the boat there. He even questioned God at first, “Why did you bring me to this place?” (He is a man you know. St. Andrew is a man like all of us, but he is special.) But when the people came to him, they were kind, they gave him hospitality. They were just fine primitive people, as are many tribes in the Amazon today, even those who fight each other.

We hear of this nowadays from people who have come into contact with “barbarian” tribes with strange customs, according to our cultures. Because they accept these people, they in turn are accepted by them. In Papua, New Guinea, in the Amazon, in the jungles of Africa, these people often embrace westerners who settle and live with them in a matter we can hardly imagine, with real love and tenderness. This happened to the apostles as well. The real problem for the apostles was when they were in the “civilized” world, not amongst primitive peoples.

So, from this place some sources say that St. Andrew went back through Pakistan and Afghanistan on the Silk Road to Sogdiana, now Samarkand and Bokhara in Uzbekistan, and not far from the border of western China – “Soh-Yok” in Chinese, which means “the ancient provinces.”

We ask now how he could have possibly gone to Sogdiana, but since archeologists and historians have found the route of the Silk Road, it is obvious that it was very accessible. All of the ancient biographers of his life say that he was in central Asia, but they don’t speak of any adventures in those places, so this means that either the texts were destroyed or nothing of note happened. Usually we only write down the difficult or the very miraculous, so if his visits were peaceful, perhaps the accounts didn’t survive.

RTE: Is Sogdiana anywhere near the Chinese region where they recently found first-century Christian inscriptions and tombs?

GEORGE: No, those tombs are at the other end of China, but there was possibly a Chinese disciple of St. Thaddeus of the Seventy, whose name is St. Aggai in the Syriac tradition. This Aggai is said to have preached in Parthia, in Sogdiana, and in central Asia: Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran and India. He found the tomb of St. Thomas in southern India, and after venerating the fragrant relics of St. Thomas, he died. His name in the Chinese sources may have been Wang-Hai – the important thing here is that according to the sources he was a silk producer and we know that no one could be a silk producer at that time unless he was Chinese. So, perhaps St. Aggai was the first Chinese disciple of an apostle of Christ. These newly-discovered Christian tombs and monuments date from about 75 A.D., so these really were apostolic times.

There are also traditions from the Yellow Sea, near Shanghai, of St. Thomas having been in China. This is not physically impossible because the area where modern-day Kazakhstan borders Mongolia and China was the cradle of the Huns, the eastern Scythians, and the Sacas. Gundophorus, the king of India who met St. Thomas, was a Sacan king, and the Sacan empire was vast, stretching from Siberia to China and India. People knew these routes, they were well-traveled.

The Proto-Bulgarians who followed the Huns even had a church dedicated to St. Andrew, although after later invasions they had to be re-Christianized. Also we have the Hephtalit Huns, a barbaric Turcik tribe who were the first Christian nation in central Asia (third-fourth century).

It is very important to understand that there are three separate traditions of St. Andrew’s missionary journeys to western China, eastern-central Asia, and Kalbin (Khalbinski Hrebet, a mountainous area on the borders of present-day Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and Russia.) One of these traditions is from Kazakhstan, another is Syriac, and the third is from the Bulgars of the Russian steppes, who migrated through Greece and eventually settled in

Italy, filling their villages with churches dedicated to St. Andrew.

According to Epiphanius,[2] a ninth-century monk historian of Constantinople, St. Andrew also went north of China, to the land of the Scythian Massagetae and Masakas (the cradle of the Bulgarians and Turks at the junction of present day Mongolia, Kazakhstan and Altai), the Proto- Bulgarian tribes, the Ungric and Trocharians, and also to the mountains of Kalbin in Altai, Siberia.

The route from Sogdiana to the land of the Massagetae was a route that Romans, Jews, and Greeks didn’t use. It was a road that the nomadic tribes used when they collected payments from the Chinese for protecting the Silk Road. Regional traditions say that St. Andrew was there, and he seems to have been accepted by these nomads, who were considered to be some of the most savage people of that time. I don’t think he was treated badly, because there are no records of misadventures in these places. This was eastern Scythia, not western Scythia which was Ukraine and Russia, and the Chinese were very afraid of the eastern Scythians. The Trocharians who lived here were Nordic, white people with blue eyes, blond hair and red beards who were living in China and in Mongolia.

RTE: A decade ago I saw people like that a little further north near the Mongolian border in Altai, Siberia. Along with the Altai who have obvious Mongol roots, they are a second native ethnic group. The Russians call them “Turks,” although they know they aren’t from Turkey, to differentiate them from the Mongolians and Chinese.

GEORGE: Yes, exactly. These people moved up into Altai through Mongolia. They were from below Kalbin, in northern Asia.

RTE: I was recently told by a woman from the Urals that there is a wide- spread Siberian tradition that St. Andrew preached as far north as the present-day village of Kazanskoe in the Russian Urals, and prophesied that there would be widespread Christianity there someday. The village has a church dedicated to him.

GEORGE: Yes, and there are many other Russian traditions about his visiting Altai, Novgorod, Karelia, and Kiev.

St. Andrew returned from Altai, and, still following the footsteps of local traditions, he would have taken a different route to the Caspian Sea through the steppes where, according to many early traditions and texts, he preached to the Alans. From there he went to Kurdistan, where he was nearly martyred. He escaped, however, and returned to Jerusalem.

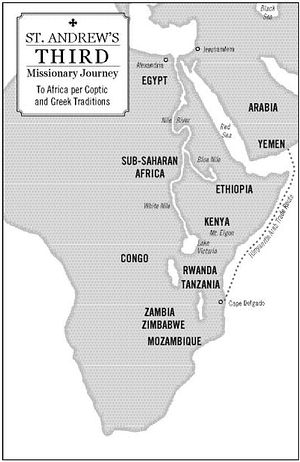

THE THIRD MISSIONARY JOURNEY:

Coptic Ethiopian Traditions

His third missionary journey, if we accept the traditions, began after the first apostolic synod in 49 A.D. This is the only point time-wise when he possibly could have gone to Africa. The sources for the African stories are Ethiopian Coptic traditions, and an apocryphal Greek source, of which we have a revised, edited Latin version by St. Gregory of Tours. If he did go to Africa, it was for a special reason, because this was not the place he origi- nally had been sent to preach. He was to preach in Bythinia, to the Greeks and to the eastern Scythians.

RTE: By “sent to preach” do you mean the tradition that the apostles picked lots as to where they would go?

GEORGE: Yes, but I think it was not only by picking lots that they decided. They organized a plan, they didn’t all just set out into the wilderness.

Now these Coptic traditions say that he made a trip to the Berber (meaning “Barbarian”) lands, but we don’t know exactly where this was because the Berbers were living from the Siwa Oasis in Egypt to Morocco, Mauritania, Mali and Niger, and were the ancestors of the present-day Kabyls (the Turaregs) in Algeria. Perhaps he simply went to a place in modern-day Egypt. From there, these sources say that he went to the land of the Anthropofagi, a very definite place in the area of the Great Lakes on the borders of Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda and Congo. Because, according to the ancient text, there was a volcano there, I believe that this was Lake Kioga, but this is my own opinion. Then, the legends say, he made his way to the abyss near Zimbabwe. According to research of the last century, the Himyarite Arabs were travelling at that time from Yemen to Mozambique to Zimbabwe, the ancient Ofir, where Hiram supposedly took the gold for King Solomon, so possibly the Jews, Phonecians, and Arabs knew this road, but not the Greeks or the Romans.

RTE: Who were the Anthropofagi?

GEORGE: According to the Coptic “Acts of St. Andrew and St. Matthias (Matthew),” an extremely colorful and fantastic apocryphal story, on his third missionary journey St. Andrew was commanded, either from heaven or by the apostles, to go and help St. Matthew because he had been captured by the Anthropofagi, who were man-eaters, cannibals.

RTE: These traditions say that St. Matthew was captured by cannibals and St. Andrew was sent to rescue him?!

GEORGE: Yes, although some traditions say that it was St. Matthias, the majority of the sources think it was St. Matthew because Matthias went to Georgia, while St. Matthew went to Alexandria and Ethiopia. The Coptic sources are definite on this.

Some people have suggested that this “land of the man-eaters” referred to in many ancient texts, was really in Pontus, in Sinope (today’s northern Turkey), but this is not possible. Sinope and Pontus were classical Greece. The only thing they can base this on is that Pausanias, a second-century A.D. geographer, came upon some isolated Greek inns where they sold dried or preserved bits of human organs as medicinal remedies, but this was never a social way of being, even in out of the way places.

RTE: Yes, but how much credence can we put in these apocryphal texts?

GEORGE: As I said, from our vantage we can’t look back in history and determine if something apocryphal was literally true, was based on something true that was elaborated on, or is a complete fantasy. There were different opinions among the Fathers. I believe St. Andrew could have been in Africa, and I substantiate this in my book, but remember, my primary task was to take every tradition, without judging the source, and try to discover if he could have physically traveled there, and, if so, how it fits time-wise and geographically with his other journeys. Admittedly, some of these can seem like wild tales to western readers.

There are many early traditions and texts, and not only Orthodox texts. Even those from heretical traditions like the monophysites may contain correct historical details. They include propaganda for their teachings that aren’t right, but these can be revised or ignored. This is why St. Gregory of Tours, writing in the sixth century, and Hieromonk Epiphanius a monk-historian in Moni Kallistraton in Constantinople in the fifth, both use the text of Leucius Charinus, who was somewhat of a Manichean. St. Gregory recounts the trav- els of St. Andrew in his “Acts of Andrew,” and Epiphanius in Patrologia Greca. They only corrected the doctrinal errors, and from this we can see that many of these early traditions were considered valid even by saints.

RTE: Can you explain how you worked with these texts?

GEORGE: It is difficult, as I spend sixty pages of my book tracing the sources of the African journey, but I will try to give you a synopsis. There are several minor sources for this tradition and two major ones: the Greek text I just mentioned of the “Acts of Andrew,” which may have been by Leucius Charinus, (later cleansed of heresy by St. Gregory of Tours in a Latin version) and the “Acts of Andrew and Matthias (Matthew)” by a Coptic source.

The original Greek “Acts of Andrew” was condemned by Pope Gelasius in the Decretum Gelasianum De Libris Recipiendis Et Non Recipiendis, which was not a synodal decree, but a local condemnation of some apocryphal texts as a reaction to the falsification of holy tradition that existed in the third and fourth century amongst heretics. This was before the Chalcedonian Council. The Decretum, although respected by Orthodox believers has never been a dogma per se, but it is a serious and enlightened guide, which everyone should consider as a valuable protection against heresy.

Although it condemns “the Acts in the name of the Apostle Andrew,” and “the Gospels in the name of Andrew,” (which were possibly the work of a Manichean gnostic, Leucius Charinus), it does not condemn the Coptic “Acts of Andrew and Matthias (or Matthew) in the Land of the Anthropofagi” nor the “Acts of Peter and Andrew” which were of Coptic origin. One might object that the Coptic texts are also forbidden under the term, “the Acts in the name of the apostle Andrew” but this reasoning doesn’t match the other cases in the Decretum where, when we have condemned texts listed as “the acts” of two people, they are described by both names (e.g. “the book which is called the ‘Acts of Thecla and Paul,’” “the book which is called ‘The Repentance of Jamne and Mambre,’” “the Passion of Cyricus and Julitta”).

The Decretum condemns “all the books which Leucius, the disciple of the devil, made…” but no one insists that the “Acts of Andrew and Matthias (or Matthew) in the land of the Anthropofagai” and the “Acts of Peter and Andrew” are the work of Leucius Charinus. On the contrary, most scholars accept that these texts are the work of an unknown Coptic monk (with the national, not the religious meaning of Coptic, because this was the pre- Chalcedonian period). This author could have been a gnostic heretic or equally, he could have been an Orthodox ascetic of the desert. We don’t have enough evidence to support either view.

Both the great church historian Eusebius of Caesarea and St. Epiphanius of Salamis[3] also condemned the “Acts of Andrew,” but not “The Acts of Andrew and Matthias (Matthew) in the Land of Anthropofagi” and the “Acts of Peter and Andrew.” As far as we know, they didn’t even refer to these texts. The reason I am even considering material that was originally from this condemned text is that in the sixth century St. Gregory of Tours corrected the heretical points in “The Acts of Andrew” by Charinus, publishing a revised text with the name “Vita and Patio” (Life and Passion of Saint Andrew,)” which has been generally approved by the Holy Orthodox Church (parts of it appearing in hymns and services, and in the Synaxarion) as a basis for the Life of Saint Andrew. In this revision, St. Gregory of Tours accepts that Apostle Andrew preached to the Anthropofagai in Africa before his trip to Achaia-Greece. He obviously believed this. His version has never been condemned by the Church, and I use it as one of my possible sources.

Neither have the Catholic or Orthodox Churches condemned the Latin “Golden Legend” of Voragine or the Anglo-Saxon epic poem “Andreas” (probably of Cynewolf) in which the old story of “The Acts of Andrew and Matthias (or Matthew) in the land of Andropofagi” re-appears in both a pious (Voragine), and folkloric (Andreas) form. This does not mean that they are accepted as historical fact, it just means that they do not contain heresy. Western scholars view them as legends.

In the Decretum of Pope Gelasius, there are other texts condemned as well: “the book which is called ‘The Assumption of Holy Mary,’” “the book which is called the ‘Lots of the Apostles’,” “The Passion of Cyricus and Julitta,” and so on. If you read these, you find that in many points they are almost identical to the holy and sacred tradition of our Orthodox Church minus the heresies. (Compare these texts and the Orthodox Great Synaxarion). Even the names “Joachim and Anna,” the holy parents of the Mother of God, are only found in apocryphal texts which have survived from this early era. This does not mean that we can consider these sources as completely true or valuable in themselves. Rather, we accept that some of what is written in them can also exist in our holy Orthodox tradition. We cannot declare that everything in them is wrong (such as the dormition of the Mother of God, when the Lord took her body and soul to heaven, the martyrdom of Apostle Andrew in Patras, the martyrdoms of Cyricus and Julitta, the tradition that the apostles “drew lots”). In fact, these condemned sources may have some true historical facts mixed with legends and fairy- tales, and poisoned by heretical nonsense. The nonsense is what Pope Gelasius condemned and what St. Gregory cleaned up. Another example of this borrowing is that Orthodox writers and church fathers have generally accepted the texts of Tertullian as a valuable historical source, although his doctrinal errors were also condemned by the Decretum.

There are other sources of this tradition of St. Andrew in Africa as well: the hymnograpy of some Pre-Chalcedonian churches (e.g. Ethiopians and Copts) and the synaxarion of the Armenians which says that “Andrew preached among the cannibals, or in the land of Barbarians (Enivarvaros), a place identical to Azania according Claudius Ptolemy. As Orthodox, we cannot ignore this, because it is very likely that these sources come from the ancient period of the unity of the Churches. If not heretical, they could be an Orthodox tradition, although this has not yet been confirmed.

There are also non-Christian historical sources saying the same thing – Arab Islamic texts that say that the Holy Apostle Andrew preached in “the land of the cannibals, that was a land of the blacks.” These sources are important because they are not Christian, they come from the early traditions and memories of the Arabic peoples.

Finally we have to remember that not every apocryphon is a forgery or a legend. Orthodox theologians and fathers have taught us to classify as an apocryphon those ancient Christian documents of unknown or unreliable validity. Some are heretical, some are forgeries, others are fantasies and romances. Some have interesting information that may even seem familiar as they incorporate real pre-existing sources (which we no longer have copies of) that are the basis of some of our Orthodox tradition, hymnography, and iconography. Not all apocryphal texts have been condemned by the Church. Of those that haven’t been condemned, our Christians fathers and theologians were free to express their own opinions. In Orthodox tradition, no human opinion is considered infallible. Only our beloved Jesus Christ is infallible, and only the Ecumenical Councils declared unmistakable truths.

RTE: Thank you, that was very thorough, and you’ve obviously worked hard to get to the bottom of these sources. Can we go on now to whether St. Andrew could have physically gotten to Africa, and what the traditions say happened there?

GEORGE: Yes. These traditions say that when St. Andrew left Ethiopia, he went to the land of the cannibals, and this is not impossible because, according to Ptolemy, the land of the Anthropofagi is some distance after the Prasum Promontory. Prasum was somewhere in the coastal area between Zimbabwe and Tanzania; African historians locate it on Cape Delgado in modern Mozambique, an ancient place where the Bantu, Indonesians, Kushites, Arabs and Greeks met to trade. It was a known and used route. The land of Anthropofagi is on Ptolemy’s map, and according to many traditions was a place inhabited by a Bantu tribe.

According to ancient Greek sources, the Land of the Anthropofagi is only in one possible place: in sub-Saharan Africa, between modern Rwanda and Uganda. The Coptic texts also speak of Prasum, Rapta, and “the land where the Anthropofagi dwell.” Their description of the land and society of the Anthropofagi is exactly like that of the Bantu people in Tororo, Uganda near Mt. Elgon and Lake Victoria today, about 300 miles from southern Ethiopia. We have the exact placement from the text: “between the Mountains of the Moon and the land of Barbaria,” and according to the Coptic text, St. Andrew left from the land of Barbaria to the land of the Anthropofagi – we even have the ancient longitudes and latitudes of these places. In the early Greek and Coptic texts the Land of Anthropofagi was called Mirmadona, and in the Bantu language today, Emere muntu na means, “the place where men are food.”

At the end of the chronicles, St. Andrew frees St. Matthew and fights with Amayel, the demon-god of these people. The accounts say he fought with the devil and with demons in many places, but this demon of the land of the Anthropofagi was so powerful that St. Andrew couldn’t fight him alone, so he asked God to send Archangel Michael to help him. Archangel Michael came, they joined forces and Amayel was destroyed. It was such a huge thing that the narratives say the people stopped their demonic practices and became Christian. According to the Coptic “Acts of Sts. Andrew and Matthias,” the native St. Plato was the first bishop of the land of the Anthropofagi.

Strangely enough, today the people of this area call the demonic spirits in this place Amayebe. Also, as a journalist I know that there is now a very strange sect, part of a guerilla force in Congo-Zaire that teaches “we must eat people to receive power,” and they are eating human flesh. The name of the sect is Amayei-Amayei, almost identical to the old name of the demon.

RTE: Is there any living tradition of early Christianity in sub-Saharan Africa?

GEORGE: There is no memory of St. Andrew’s presence or of early Christianity except in Ethiopia. Until recently, most of sub-Saharan Africa had no written traditions, and at first I was shy to write that even a small group of Bantu fighters have gone back to cannibalism. I thought, “This is going to be an insult for the Bantu,” until I realized that many people during their history have been cannibals. One doesn’t have to be embarrassed that a few Bantu may have turned back to cannibalism; what is important is to understand that the devil himself is fighting the Bantu people because they have a special grace of God. It is natural that they would be attacked, that the evil one would corrupt the soul’s longing for the body and blood of Christ because he wants to keep them away from God – Africans are coming to Christianity by the millions.

If you go to Orthodox churches of the Bantu you see a faith that is real and miraculous. In the Orthodox churches of Africa miracles are part of the every-day life of the people. They have miracles, but they also readily accept things we cannot, like death and disease, with great faith in the will of God. They have miracles but they are not seeking miracles; that is the Protestant way. They can accept the non-miracle as a miracle as well, as God’s Providence.

If he indeed went there, St. Andrew could have returned through Ethiopia, then taken the road to Meroe, up the Nile and back to Jerusalem, which was a well-known route for the Greeks and Arabs.

RTE: Are there also traditions of St. Andrew preaching in Ethiopia?

GEORGE: Yes, we have local traditions of him in Ethiopia from Coptic manuscripts and some early traditions of the Church that are not easily understood now. For centuries we thought they were just legends, but if you read the geographical notes, they precisely describe the kingdoms of Ethiopia at that time, the Meroitic Kingdoms. But these texts describe them in a way that only Copts can easily understand that this is Ethiopia. For example, in America you won’t always say, “San Francisco.” You may say, “the Golden Gate,” or “the Bay Area,” or in the 1950s you could have said, “Frisco.” In New York you say, “the City.” It is the same with the term “the sacred mountains.” Every Ethiopian understands that this was Gebel Barkal, but only if you are Coptic or Ethiopian do you know this.

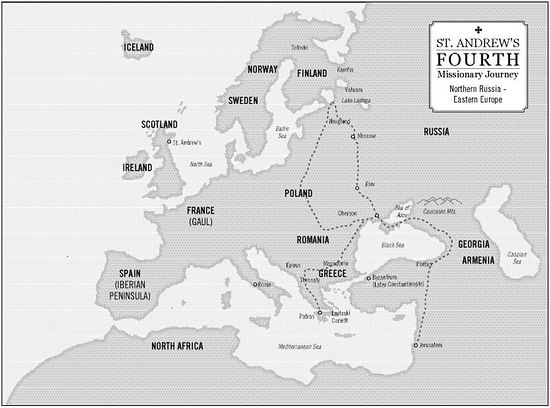

THE FOURTH MISSIONARY JOURNEY:

To the North

After the dormition of the Mother of God, St. Andrew began his final journey from Jerusalem. The trail of tradition says that he went back to Pontus, then to Georgia, to the Caucuses, and to the Sea of Azov in southern Russia. From there he went to Donets, to the Crimea, up the Dnepr River to Kiev and to the Scythians of the Ukraine. In the Crimea, where he stayed with the Greeks of Sebastopol and Cherson, we know that there were first-century Christian communities organized by St. Andrew himself. From the Crimea and Kiev in the Ukraine, he would have gone north by river to what is now Moscow, to Novgorod and then to Lake Ladoga (Valaam). Early written narratives no longer exist, but this is a very likely route because the river trade from Crimea to northern Russia and Karelia (Lake Ladoga) was common and relatively easy. Extensive trade from the south is attested to by the great number of Roman and Byzantine coins found in Valaam and Karelia. There is also a local tradition that he went to Solovki, and they’ve found some very old coins in the Solovki Islands in the White Sea depicting St. Andrew, but we can’t claim he was there solely on the basis of finding coins with his image. We can’t completely exclude this legend, because it might be true, but we have no historical evidence to support it. Conceivably, he could have traveled from Valaam to Solovki with the Lapp reindeer herders who moved between Solovki in the summer and the protected shores of Ladoga in the winter.

Although we don’t have extremely early texts, the accounts from Lake Ladoga and Valaam are not legends, they are tradition. We have an 11th century Russian text and we also have the tradition of Valaam itself. From Valaam it appears that he went to the Baltic Sea (then possibly to Scotland and back to the Baltic, although, as I said earlier, this is not certain). Then, through Poland and Slovakia to Romania, where he settled for twenty years.

Finally, he went back to Sebastopol (Crimea) to Sinope, and then to Greece and to his end in Patras.

We can trace his return route on this fourth journey because we have traditions for him during this time in Poland, Byelorussia, and even in Germany, although this is doubtful. We also have solid traditions for him in the lands of the Goths, although before the Goths moved into the Ukraine they lived in Poland alongside Germanic tribes. Possibly he returned through modern-day Poland and the tribes that later moved up into Germany carried the tradition of St. Andrew’s passing with them, but we can’t say that he was in Germany itself.

It was on his return south that he settled in Romania for twenty years. During that time he traveled in Moldavia and Bulgaria, on the Danube and along the coast of the Black Sea, but mostly he was in and around his cave in Dervent, Dobrogea, in southern Romania.

St. Andrew’s Romanian cave is still kept as a holy place and Romanian Orthodox have gone there on pilgrimage for almost two thousand years. We also know the locations of other caves he lived in: in Pontus near the Black Sea (now Turkey), in Georgia, in Russia, in Romania, and in Loutraki near Corinth. It is all him, the same man.

RTE: Why did he stay in Romania for so long?

GEORGE: I didn’t understand this myself at first, but it appears that he felt very close to the Romanians because they were monotheists. According to Flavius Josephus, their clerics were like Essenes. They were virgins, strict vegetarians who didn’t even eat fleshy vegetables, but only seeds and nuts like ascetics in the desert. Dacian society was very free, the women had a good, equal position there, not like Greco-Roman society, and the Dacians didn’t keep slaves. In fact, they were unique in the world at that time because they didn’t have slaves. According to Romanian traditions and archeological findings, the Dacians became Christian under St. Andrew himself in the first century. It is natural that he would have felt at home with the Dacian clergy and that they would have readily accepted him and converted.

The Ethiopic tradition also describes St. Andrew as a very strict vegetarian. This is possible because, although most of the other apostles were married, both he and John the Evangelist were virgins. They had been disciples of St. John the Baptist and followed his hesychast tradition. They were the first monks and ascetics of the Christian world. Even in our Orthodox hymnography we remember St Andrew as being closely associated with St. John the Baptist. In Orthodoxy we have choices: we have vegetarian hermits, sometimes very strict, living only on bread and water all their lives, and we also have saintly kings who ate pork and beef.

He was in Romania for twenty years and I think he loved this land more than anything after being with Christ. I believe that God allowed it as a consolation because he had been on such difficult missionary journeys. We have descriptions of places where he wasn’t welcome, where he was forced to leave and his despair over this. Things were often very difficult, particularly when he was in the Slavic lands where human sacrifice was still practiced.

You can imagine, he was tired of living with this, and when he came to the Dacians, who had no slaves, where men and women were equal, where Jews and Greeks were accepted in the same manner, and where there were ascetic hermit-priests, you can understand how easily he fit in. He was able to teach, he was happy there. In fact, they thought that the religion he brought was not only better than theirs, but was a continuation of their old religion. They saw their native religion as a foreshadowing of Christianity. Twenty years is a long time, and you can understand why the Romanians remember more of him than any other tradition.

From Romania there are traditions that he went to Cherson in the Crimea and from there to Sinope, to Macedonia, and preached a bit in Epirus (northern Greece and southern Albania). Although we have references from early texts that he preached in Epirus, we don’t have any local traditions there. The rest of the sites I’ve quoted are supported by both written texts and oral tradition.

To be continued.

Reprinted in part with permission from

The Road to Emmaus