In the Apostle’s Creed (an early Roman baptismal statement of faith) a person confesses belief in “the communion of saints.” While this creed is not widely used in the East, it is important that we understand the communion of saints as a matter of both ontology and incarnation—it is related to the essence or ‘being’ of the Church itself as the true Body of Christ.

In other words, when we speak of the communion of saints, we really mean it. It is something both experienced and felt. Beyond theory or doctrinal speculation, the communion of saints is about incarnational, actual, and true relations between the Christians on earth and those reposed in the Lord.

In Christ and through the Holy Spirit, we are all dwelling in unity across space and time, and this is most apparent and fully realized in the celebration of the holy Eucharist. Not only are we partaking of the true Body of Christ in the Eucharist, but we are also ourselves being transformed into the true Body of Christ, the Church, by that participation.

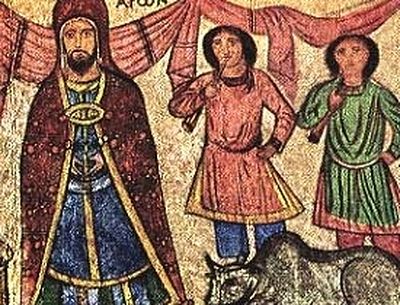

In the veneration of both icons and relics, we experience the union these great men and women shared with Christ on earth decades or even centuries ago—a unity that transcends time and continues through eternity. Christ unites himself to us, both body and soul, and the bones of martyrs shine with the uncreated grace of God while their souls are at rest, working miracles even after their death (2 Kings [4 Reigns LXX] 13:21; Acts 5:15 & 19:12). This piety is ancient, and it is demonstrated already in the earliest days of the Church.

For example, St. Ignatius of Antioch, a disciple of the apostle John, was martyred in the city of Rome near the end of the first century (ca. A.D. 98). For his faith, and especially as a bishop, he was thrown to lions in front of a cheering crowd. In the hagiography written by his disciples, it is recorded:

[O]nly the harder portions of his holy remains were left, which were conveyed to Antioch and wrapped in linen, as an inestimable treasure left to the holy Church by the grace which was in the martyr. Now these things took place on the thirteenth day before the Kalends of January, that is, on the twentieth of December. —The Martyrdom of Ignatius, chs. 6–7

The Christians in Rome who witness his execution gather his bodily remains, which they then take away for his flock in Antioch. The relics of Ignatius are treasured because of “the grace which was in the martyr,” and miracles are attributed to his fervent intercessions soon after. Again, this took place at the end of the first (or beginning of the second) century. Ever since, the Church has venerated St. Ignatius on the 20th of December, the day of his martyrdom.

Another early saint of note is Polycarp, also a disciple of John (ca. A.D. 69–155). The beloved apostle appoints Polycarp as bishop of Smyrna, and he too would die a martyr. For the sake of our present discussion, it is on his life—and not his death—that I wish to focus. In the Life of Polycarp (ch. 20), the martyrdom of another Christian is mentioned:

So having taken the body of the blessed [martyr] Bucolus to Smyrna to the cemetery in front of the Ephesian Royal gate—placing it where recently a myrtle tree had sprung up after the burial of the body of Thraseas the Martyr—when all was over, they offered bread [the Eucharist] for Bucolus and the rest.

Note the miraculous myrtle tree, growing immediately from the place where another martyr Thraseas had been buried. In his edition of this hagiography (p. 150), Alistair Stewart-Sykes notes that the body of Thraseas was actually taken from the place of his initial burial to the cemetery in Smyrna—the first recorded example of the “translation” of a saint’s relics. The translation of relics is an important event in the life of a Saint still commemorated by the Church. The most recent example of note would be the Vatican’s return of the relics of Ss. John Chrysostom and Gregory the Theologian back to the Ecumenical Patriarchate in 2004. These relics were stolen during the Fourth Crusade.

Here also is an early example of the celebration of the Eucharist upon the tomb of a martyr. A related practice was the depositio ad sanctos, or the burying of a reposed Christian adjacent to the relics of a martyred saint, showing reverence for the holiness of even the dirt surrounding their bones (The Cult of the Saints, p. 11). Shrines were built for the relics of martyrs, and liturgies were offered in their presence on at least an annual basis; typically, on the anniversary of their martyrdom. This was being done by as early as the second century (e.g. Tertullian, On Exhortation to Chastity 11; cf. St. Augustine, Confessions 6.2.2).

It soon was common for new churches to be built either over the translated relics of a saint, or at the very place they had once been martyred. The altar itself was consecrated with the bones of saints, or was in actuality the martyr’s stone tomb. This was seen by many in the early Church as a fulfillment of the Apocalypse: “When he opened the fifth seal, I saw under the altar the souls of those who had been slain for the word of God and for the witness they had borne” (Rev. 6:9).

This early practice of celebrating the Eucharist over the bones of martyrs is later codified by Canon 7 of the Seventh Ecumenical Council (A.D. 787), where it is dictated that a church building should not be consecrated without the relics of a Saint:

VII. That to churches consecrated without any deposit of the relics of the Saints, the defect should be made good.

Paul the divine Apostle says: “The sins of some are open beforehand, and some they follow after.” These are their primary sins, and other sins follow these. Accordingly upon the heels of the heresy of the traducers of the Christians, there followed close other ungodliness. For as they took out of the churches the presence of the venerable images, so likewise they cast aside other customs which we must now revive and maintain in accordance with the written and unwritten law. We decree therefore that relics shall be placed with the accustomed service in as many of the sacred temples as have been consecrated without the relics of the Martyrs. And if any bishop from this time forward is found consecrating a temple without holy relics, he shall be deposed, as a transgressor of the ecclesiastical traditions.

Before falling away, Tertullian of Carthage wrote in a brief defense of the Christian faith (Apologeticum, ca. 197):

We are not a new philosophy but a divine revelation. That’s why you can’t just exterminate us; the more you kill, the more we are. The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church.

In a very real and substantial sense, it is the blood and bones of the martyrs that has built our holy Church, and these words could not ring more true. After all, Christ himself is the true and faithful Martyr (Rev. 1:5).

Of our Church, the apostles and prophets are the foundation, while Christ himself is both Head and cornerstone (Eph. 2:20 & 5:23). Not only do we benefit from their example of faith in imitation of Christ, but we also communicate with them in his one, true Body. We partake of one another, and the grace of the Holy Spirit binds us together. The whole loaf is made to rise by the leaven of their individual sacrifice and by their continued intercessions in the throne room of God.

While true worship is offered to the Trinity alone, we make it a point to honor the Saints. They surround us in worship as a great cloud of witnesses (Heb. 12:1)—as a great cloud of martyrs (“witness” is the same word as “martyr” in Greek)—praying that we too could endure to the end, and be saved. When temptation comes, their bones and their blood cries out from across eternity: “deliver us from evil.”

And for some, as it was for those martyrs before us, that deliverance from evil is straight into the waiting arms of Christ.