No one wants to feel like a fool. When it happens, our faces flush, we turn our eyes away (usually towards the ground). We usually want to hide or disappear, and, just as likely the burn in our face quickly passes to the hot burn of anger. Often what follows are words or actions we regret later. Having felt like a fool, we often act like one, unable to muster the calm deportment that time and distance might allow. Since all of this is true, and pretty universal, it is deeply surprising to discover that there are great saints who have chosen to make fools of themselves for the sake of their salvation and the salvation of others. Indeed, it is perhaps still more surprising to learn that feeling like a fool may be necessary for everyone, everywhere, if they want to be saved.

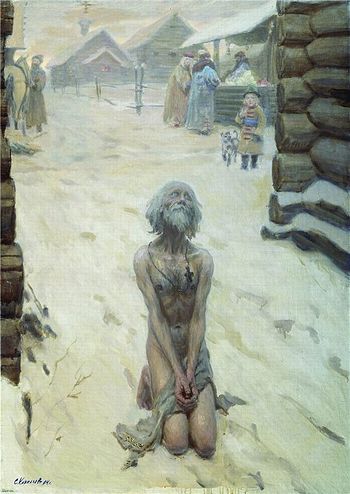

A newly translated Russian novel brings the character of the Holy Fool (юродивый) into the range of a much wider audience. Laurus, written by Eugene Vodolazkin, offers the story of a fictional holy fool. However, many of the elements of the novel are based on the stories of true, historical holy fools, both in Russia and elsewhere. But most striking is Vodolazkin’s reflection on the interior world of the fool. It is, doubtless, the most difficult part of the story to make believable and understandable to a modern audience. Non-Orthodox readers may very well misunderstand or even be repulsed by what they read. However, I believe the novel has largely succeeded in what it tries to present. It represents a very powerful and plausible presentation of the spiritual power in holy foolishness.

Several ideas are essential for understanding Vodolazkin’s holy fool. First is the understanding of the participatory nature of our existence. The fool in the novel is responsible for the death of a woman and her child. The woman should have been his wife, but his own pride and unacknowledged shame prevented him from marrying her. In the same way, his hiding her from the public caused her to die unconfessed, without communion, and without the assistance of a midwife, ultimately resulting in the child’s stillbirth. The fool is plunged into despair and devastation. Lying at the point of death, he is visited and spiritually rescued by a holy monastic elder:

The elder turned to Arseny. Arseny stared straight ahead, unblinking. His palms were lying on his knees. A fly crawled along his cheek. The elder shooed away the fly, took Arseny by the chin, and turned his face toward him. I will not pity you: you are to blame for her bodily death. You are also to blame that her soul may perish. I should have said that beyond the grave it is already too late to save her life, but you know what, I will not say that. Because there is no “already” where she is now. And there is no “still.” And there is no time, though there is God’s eternal mercy, we trust in His mercy. But mercy should be a reward for effort. (The elder had a coughing spell. He covered his mouth with his hand and the cough puffed out his cheeks as it tried to escape.) The whole point is that the soul is helpless after leaving the body. It can only act in a bodily way. We are only saved, after all, in earthly life.

Arseny’s eyes were dry, as before:

But I took away her earthly life.

The elder looked calmly at Arseny:

So then give her your own.

But is it really possible for me to live instead of

her?

If approached from the proper perspective, yes.

Love made you and Ustina a united whole, which means a

part of Ustina is still here. It is you.

Arseny (the holy fool’s name at this point in the novel – he bore four different ones in his lifetime) sets out on the life journey that will become the path of a holy fool, sainthood, and his salvation. The novel traces his slow descent into poverty, sickness, delirium and renunciation. At one point, he becomes famous for healing; later, he becomes a total fool who no longer speaks; he travels as a pilgrim to Jerusalem. In all of the transformation, however, he carries within himself his union with Ustina and their child. Every effort of his life is for her and never for himself.

It is interesting to compare this book to Hesse’s Siddhartha, a book of spiritual transformation within a Hindu/Buddhist model. Hesse’s hero becomes enlightened in a manner that ultimately seems attractive. Who doesn’t want to be a Buddha? Vodolazkin’s hero never beckons you to follow. His path is always downward until it is finished. And even in its completion, he extracts a promise that his body will be dragged into the forest and left for the animals.

I have already read this book twice, within about six weeks, and will probably read it soon again. Its brilliance is the author’s willingness to let his character follow his path faithfully and to the end. He is helped by drawing continually on various lives of saints and holy fools. What Laurus/Arseny does, has been done before, for real.

I suggested earlier that his path of foolishness is necessary to salvation for everyone, even if not to the same extreme. In the words of the Elder Sophrony, “The way of shame is the way of the Lord.” There is a place for that in confession, but it also should hold a place in our daily lives.

This, of course, can be alarming news to some. Shame has rightly earned a bad name, particularly as an experience of toxic emotions. It is associated with spiritual abuse and many of the worsts things in human relationships and in religious experience. But this is the abuse of shame. Shame is our experience of “who we are” (not “what we have done”). Being told that you are of no worth (or worse) can be among the most devastating moments in life. Shaming conversations tend to linger for years, even for a lifetime. But toxic shame has a striking characteristic: it is not voluntary. As such, it is an effort to emotionally control, even destroy another human being. It is demonic.

However, there is a shame that is voluntarily accepted (for various reasons). It is, in fact, the heart and core of humility. Christ Himself bore our shame, we are told, but He also tells us, “No one takes my life from me. I lay it down of my own accord.” And indeed, in the Scriptures, God is not the source of shame. Adam and Eve find themselves ashamed of their nakedness, but God provides them “garments of skin.” (Gen. 3:21) Our voluntary shame represents, not a toxic, destructive act, but an act of vulnerability. We expose ourselves to the view of others and in so doing, come to know our true selves, and through that to know Christ.

Most of the time, our true lives remain hidden from others. How we dress, indeed much if not most of our public behavior represents an effort to present a public face. This is perfectly normal and not an aberrant behavior. It is a behavior that takes on some aberrant forms, precisely because the shame that marks our lives on a deep level is often painful and toxic. The greater the pain, the greater our perceived need to hide and protect ourselves (except when our shame is reversed into a form of exhibitionism). But even our private lives seldom have moments when our “guard is down” and we are utterly candid. The difficulty associated with confession is symptomatic of how difficult it is to be truly candid.

The sacrament of confession, at its best, is an island of safety, a place where our willingness to be vulnerable trumps our shame and allows us to express our true self. As such, confession provides a mirror where we allow ourselves to come face to face with our true self. We are told in Scripture that we are transformed as we move towards beholding Christ “face to face” (1 Cor. 13:12). Our true self represents our “face.”

Revealing our true face is generally experienced as an act of foolishness, or certainly carries our fear of “feeling like a fool.” Many people are afraid that their priest will think badly of them after their confession. That fear often surrounds the words of our confession with qualifiers and explanations, efforts to maintain some last shred of hidden identity.

The holy fools fly in the face of this deepest of human emotions. To a certain extent, their actions mock our fears, and frequently reveal the truth of our lives. Their voluntary foolishness unmasks our own efforts to hide our foolish self. It is interesting that the phenomenon of the holy fool has had such a wide and persistent presence in Orthodoxy. To a certain extent, holy foolishness lies at the heart of the monastic vocation. What kind of a fool would want to give up every intention of family and children and renounce all property? What kind of fool lives in a cave and nearly starves? Of course, over time, monasticism has acquired its own patina of acceptability, even provoking admiration. The holy fool in history frequently mocks such pretense and forces even monastics to come to their senses and face the truth of their naked existence.

As I noted earlier, holy fools represent an extreme. The novel, Laurus, assembles many of these extremes into the narrative of a fictional life. The story of a soul’s salvation is perhaps the hardest thing to describe. Dostoevsky said that goodness was the most elusive quality in a character. Most importantly, the holy fool unmasks the nature of our false foolishness – our own efforts to create and maintain an identity that is little more than fiction. To quote CS Lewis, “How can we see Him face to face until we have faces?”