In this lesson Dr. Jeannie addresses a question about the nature of sin, forgiveness, and judgment, then begins the topic of apostolic Tradition regarding Christ’s Resurrection.

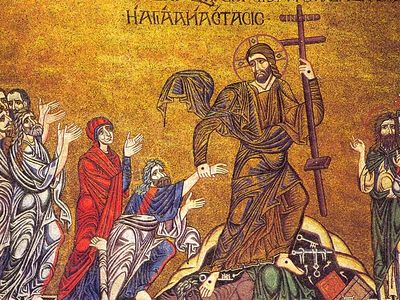

Christos Anesti! Christ is Risen!

Christ is Risen from the dead, trampling down death by death and upon those in the tombs bestowing life.

Today we will continue our discussion on the Resurrection by studying an important passage about the Resurrection found in the New Testament. I did forget to mention in the last podcast when I was talking a little bit about the difference in the perception—in the understanding of sin and the crucifixion in Orthodoxy and Catholicism. I forgot to mention about one of the best resources and easiest resources for learning about Catholicism, and that is the Vatican website which is Vatican.va. Or you can just type in “Vatican website” in a search and it will come up very easily. Well, first of all you can choose the language you want to search in when you type that in, Vatican.va. You’re given an option of various languages. You can click on English, or some other language you prefer, and then you can search for a word in a box which appears on the upper-right side—there’s search engine. For example, you can type in “indulgence” and all kinds of information about indulgences, papal documents, etc. will come up. Or you can type in “canon law” and get all of the canon law, etc. in English. So it’s very useful for learning about Catholicism and “official” Catholic doctrine.

Now about the question from the last lesson. My husband, Fr. Costa, does not approve it when I begin the podcast with questions relating to the prior lesson. He thinks I should leave the questions for the end and just begin with the lesson. I prefer to begin with the questions since they are related to what was discussed before, and then proceed to the lesson. But this is the kind of ongoing discussion in our family. If you have an opinion about this, I’d appreciate it if you would let me know… You can contact me by writing to searchthescriptures@ancientfaith.com or on the website. At the podcast site under my picture it says, “author email,” and if you click on that the email address will come up.

So, a listener wrote to ask me about my comments that sin is seen more as an illness requiring healing than a crime which requires punishment, and this person felt that didn’t seem to fit the prayers of the Orthodox Church in which we constantly ask God for mercy. I haven’t thought about that, but I can see why someone would assume that the prayers of the Church, such as the Jesus prayer, which is extremely important, or other services in which we frequently ask God for mercy, we frequently repeat the petition “Lord, have mercy.” This is a very good question. So then why do we say, “Lord, have mercy”? Or why do we go to confession? Not because we think of sin as a “crime,” but because we have offended God by violating what’s expected of us in our relationship with God. If you think of it in terms of a human relationship, it would work much the same way. If you wish to have a relationship with anyone, you have to nurture it. If you offend them or violate the expectations of the relationship, the roles in the relationship, you need to say you’re sorry and ask for forgiveness, because if you don’t, especially if you consistently fail to ask for forgiveness because of your pride, you simply damage the relationship and you find yourself distant from that person. So asking for forgiveness from those whom we have offended, whether they’re other human beings or God, heals the relationship. Failing to seek forgiveness or mercy from other humans leads to alienation.

Now, asking for mercy when we say repeatedly “Lord, have mercy” is also a way of remembering who God is and who we are. When we offend God by sin, we need God’s forgiveness; and asking for forgiveness also keeps us humble. Another thing that is very useful, is that it reminds us that we are all sinners and we can never stand in judgment of others. This unfortunately is one of those verses in the Bible that is frequently misunderstood: Judge not, lest ye be judged. So people say, “Oh, you’re judging, you’re judging!” as soon as you point something out as a sin. That’s not judging. In fact, the Gospels require us to point out when someone has committed a sin because that’s for their good. It’s not a sin to point to something and say, “That’s a sin, what you’re doing.” “Judging” is to say someone is going to hell because we can never say that—for a number of reasons.

First of all, this is something known to God alone. Secondly we don’t know the outcome of someone’s life. As we saw from our earlier podcast on the crucifixion, in a moment the thief on the cross was saved; so, no one stands in a position to decide who will go to heaven and who will go to hell. In certain Protestant traditions, there are people who insist that they are saved and that they know they are going to Heaven. And I think that it’s very interesting when you think about it: They don’t ask for the mercy of God in their prayers, because of course they know they’re saved. But unfortunately, very often—and you see this sometimes in their literature, in their speech—that they are the most harsh and the most judgmental, because when you say, “I am saved”, you are also saying, by implication, that someone else is not. And this is very spiritually dangerous. Claiming salvation suggests that we don’t need the mercy of God, but this is spiritual pride. It’s a way of deluding ourselves from thinking that we are already righteous in the eyes of God. We sound just like the Pharisee in the parable of the Publican and the Pharisee who thought he was justified in the eyes of God. But instead the one who humbled himself before God was the one who was accepted. So asking for mercy does not mean we think of sin in legalistic terms, like crime and punishment, but it is simply a way of repairing the relationship with God, of healing the relationship that we have damaged because we have turned away from God because of our sins. So that’s the answer to that question.

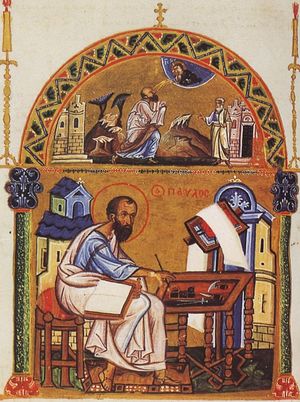

I said in the very first series on the Resurrection that we would discuss the oldest written account on the Resurrection, an account that is even older than the Gospels; and I wonder if you have figured out where that could be found. It is in one of the epistles of St. Paul, 1 Corinthians 15. So if you said “that’s the one!” you were right on the money. This is the earliest written account of the Resurrection appearances of Christ. It is an extremely important passage in the New Testament; I would say one of the most important, because of the importance of the Resurrection. Now it may surprise you to learn that this is in the epistles of Paul, and this epistle is older than the Gospels. Why do I say that this is older than the Gospels? Because after all, the Gospels talk about a period of time that is earlier than Paul’s epistles, but the Gospels in fact were probably written after Paul’s epistles, at least in the form that we now have them. The epistles of Paul are the oldest parts of the New Testament, because they are contemporaneous with the time that Paul was active—for these are letters. An epistle is a fancy word for a “letter.” So when Christ rose and sent the apostles out to preach, they went out around the world busily preaching the Gospel. And this was the time period during which Paul was writing his epistles. So we’re talking about a period of time within the couple of decades after the Resurrection of Christ—and St. Paul, of course, never imagined that he was writing Scripture. He was simply writing letters to his communities, answering questions that they raised, responding to the crises and problems within them. And these letters are very important from a historical perspective as the earliest parts of the New Testament, because they give us a little bit of insight into the issues and problems in primitive Christianity.

So, St. Paul’s epistles are contemporaneous with his missionary activity, whereas the Gospels were not written at the time that Christ was preaching, or even right after the Resurrection, because there was no need to write a Gospel right after the Resurrection. No one imagined that they needed to do that, because they had the apostles. They had eyewitnesses. There was no need for a written Gospels. They had the apostles to serve as eyewitnesses to the teachings and the Resurrection of Christ, and the oral teaching, the oral apostolic tradition was considered superior to any kind of writing. So because there were plenty of apostles alive, and because there were eyewitnesses already in existence, and also because they believe that the Lord was going to return very, very soon, it never occurred to them to sit down and write the Gospels until a little bit of time had passed. They figured the Lord would come back; and there were plenty of eyewitnesses, so why put these things to writing? But as the apostles started to die and it appeared that the Lord was not going to come back as quickly as they thought, (because He never said He would come back very soon—they just assumed that), some people started writing down the Gospels. It’s very difficult for us to understand how something that is an oral tradition is more acceptable, more believable, considered superior to something that is in writing, because we are more likely to believe something if we see it in writing, especially in a book. But in in antiquity people were less likely to believe something in writing because all books were hand copied. Anyone could write a book and attach someone’s name to it, or they could copy a known, existing book and then change the contents. So you could never be confident about a writing. You couldn’t have confidence that what you were reading was a true, genuine copy of the original document, or that it was accurate. That’s why the oral tradition was considered superior and more trustworthy: because when you learned something orally, you knew who taught you and you based your trust and confidence on that person.

Somebody like St. John, for example, teaches Polycarp, who later became the bishop of Smyrna. And then he teaches Irenaeus, so Irenaeus becomes the bishop of Lyon way towards the end of the second century. He says, “My teacher was Polycarp, and Polycarp’s teacher was John, and John’s teacher was the Lord.” So isn’t that interesting? He knows exactly who his teachers were and therefore he has confidence in the authority of the message and the truthfulness of the message. Now, for example, you can see this in the book of Revelation, which curses anyone who tampers with its contents. This was a real problem in antiquity, and this kind of curse or a warning, not to tamper with the contents of a book by adding or removing anything, was also found in other books in antiquity. So the oral tradition was more important than the written tradition, and it just so happens that what we have in 1 Corinthians 15 was the oral tradition that was being passed around at that time about the Resurrection of Christ. And it just so happens that Paul writes it down, because he’s responding to this question of the Resurrection. Thus, it’s almost by accident that we have this earliest written account of the Resurrection of Christ. It is preserved for us by St. Paul, as I said, almost by accident—he’s only including it because it’s an issue in the Church of Corinth.

The belief in the Resurrection is an issue (can you imagine that?) as early as this, and we’re talking about the year 54 or 55. It’s only about twenty years after the Resurrection, and people are already questioning the Resurrection. They are not necessarily questioning the Resurrection of Christ. They don’t seem to be arguing that Christ Himself did not rise, but they don’t seem to believe in the general Resurrection of the dead, that is, that they might rise. So we’re going to discuss this passage about the Resurrection, which as I said is extremely important. But let me just tell you that the Church of Corinth had a lot of problems. There were many, many issues that they were facing and many of them quite serious, but Paul addresses their belief in the Resurrection—or lack of belief in the Resurrection—at the very end, to end with the most important point that he wanted to make. It’s a culmination of all of the advice he gave them. He addresses at least ten different problems that this community was having; and lastly, in chapter 15, talks very extensively about the Resurrection and about the importance of the Resurrection.

There is a way that we can date the activities of St. Paul and also his epistles based actually on the time that he spent in Corinth. There are a couple of key dates that we know about from history that allow us to do this, and when we arrive at the study of St. Paul in our introduction to the Bible I will explain it to you. But this letter is dated around the year 54 or 55. I’m going to read the first 11 verses for you, and then we’ll discuss them point-by-point. This is from the New King James translation in your Orthodox Study Bible, but any other translation would be fine if you wish to follow along. So listen carefully to this: Moreover brethren I declare to you the Gospel which I preached to you, which you also received and in which you stand, by which you are saved, if you hold fast that word which I preached to you, unless you believed in vain. For I deliver to you, first of all, that which I also received, that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that He was buried and that He rose again the third day according to the Scriptures, and that He was seen by Cephas, then by the twelve. After that, He was seen by over 500 brethren at once, of whom the greater part remained to the present, but some have fallen asleep. After that He was seen by James, then by all the Apostles, then lastly of all He was seen by me also as by one born out of due time, for I am the least of the apostles, who am not worthy to be called an apostle because I persecuted the Church of God. But by the grace of God, I am what I am, and His grace toward me was not in vain, but I labored more abundantly than they all. Yet not I, but the grace of God which was with me. Therefore, whether it was I or they, so we preach and so you believed (1 Cor. 15:1-11).

Let’s begin with the first couple of verses. He begins—and this, again, is the culmination of his instruction. That’s why he says, “Moreover brethren, I declare to you.” What does he say? “Moreover brethren.” Meaning, “in addition,” “finally,” “let me top it off.” I declare to you the Gospel which I preached to you, which you also received and in which you stand.” What does that mean? “I declare to you”. He’s reminding them about the Gospel he preached. What does he mean by “gospel”? “Gospel” here, of course, is not a book, because the books don’t exist yet. The gospel is the Message, the Good News, the Evangelion. I’ve spoken about this before. It is the core set of Christian beliefs. This is the “gospel” that he preached, and the word preached is also the word “gospel.” “Evangelion”, “Evangelizo”. It’s also a verb in Greek, so “I gospeled you the Gospel,” “I preached to you the Gospel.” We can’t do that in English, but it’s very effective; it really emphasizes what the gospel is and the heart of the gospel is the Resurrection. He said, I preached this to you. I evangelized you with the Evangelion, and you received it, you accepted it, you believed. You became a Christian and you stand in this. This is the foundation of your faith. This is what you said you believed; that is, the Resurrection of Christ and these other things. And also, this is the means by which you’re saved, if you believe this, which I preached to you—“unless you believed in vain.”

What does he mean by “in vain”? The word is “eiki”. What does he mean by that? It means something which is useless, pointless, of no help whatsoever. So if you believed “in vain,” your faith, your belief is pointless. If you don’t accept this, which I’m going to tell you about, your faith is pointless. So he’s setting up to remind them of what he taught them and what they accepted when they signed on as Christians, what the foundation or their faith is, unless their faith is absolutely pointless and absolutely useless and of no account whatsoever.

So these first two verses are reminding them of what he first taught them when he first came to Corinth back in around 49 or 50, just a few years before. In verse 3, he’s about to tell them what he taught them in order to remind them: “For I delivered to you, first of all, that which I also received.” Now what is this word “delivered”? This is the verbal form of the word “tradition.” “Paredoka”, “I delivered to you.” This is the verbal form of the word “paredosis”, which is “tradition.” Again, this is another word that has a noun for in English but no verb form. “I traditioned to you the tradition” is what he’s saying. In Greek, it means to hand something over to someone else: “paredosis”. That’s what the root meaning of the word “tradition” is. “Tradition” in English has its root in Latin, but it has the same exact meaning in Latin: “traditio.” This word means the same thing: to hand something over; and for the same reason it is also the root word of the word “traitor.” A traitor is somebody who hands another person over, and it’s exactly the same in Greek. The Greek word for “traitor” also comes from the root of the Greek word for tradition, “paredosis." So it’s something that he’s handing over to them. He handed over to them, first of all, that which he also received, “en protis.” Some translations of the Bible say “of first importance”. That is also the intended meaning here. He first taught them this, and it’s also of first importance. So either way you want to understand it is perfectly acceptable.

So, this is the first thing he taught them and it is the most important thing, and he himself had received it—he passed on to them something he had himself received. Now, the Orthodox Study Bible says that Paul had received this tradition as a personal revelation from Christ, but I don’t agree with this (that’s a footnote here). It is true that Paul did receive personal revelations, but I don’t think that that’s what he’s talking about here.

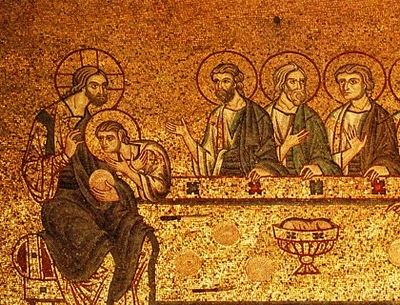

Very interestingly, we have a very similar introduction to another extremely important passage in 1 Corinthians. In 1 Corinthians 11, St. Paul preserved for us the early oral tradition of the Last Supper, and that happens to be the earliest written account of the Last Supper, so now you also know where that is. It is also in 1 Corinthians, because they were having some problems in their worship services, and so he reminded them of what he taught them about the Lord’s Supper. He says “I delivered to you what I also received.” But there he says, “What I also received from the Lord.” Here [in chapter 15] he doesn’t say that, and I think that Paul is expressing his own catechism. He received that and then when he went out to teach them. He taught them the same oral tradition. Paul was also catechized. There was no way that he was not. He definitely had revelations from the Lord, but he didn’t learn everything by revelation from the Lord. He also learned the apostolic tradition and passed it on just as he himself had received it. And that’s one of the important things in the concept of tradition: that you preserve what you receive, you don’t just take part of it, the part that you like, and pass that on and leave the rest behind. You pass it on whole, entire, well-preserved. So this is also extremely important.

In the Orthodox Church, we understand what Tradition is. The other churches have their own traditions, but they don’t adhere to Apostolic Tradition to the extent that we do. And frankly, that is the reason for our very strong unity of faith, for the fact that we do not have tremendous theological factions. We don’t have a wide-variety of opinions about basic doctrine and practices because we have made it our point to keep the Apostolic Tradition unchanged. That’s really the distinguishing characteristic of the Orthodox Church, this is exactly what St. Paul is talking about, and this is the meaning of Tradition. This, frankly, is the role of the bishop. You see, the bishop now stands in the place of the apostles. There are no more apostles, but the bishop stands in the role of the apostles. When an Orthodox bishop is ordained, the first thing that he does is recite the Creed. Why does he stand up in front of the congregation and recite the Nicene Creed? He’s says, “I believe in one God the Father Almighty,” and he recites the Creed, so that you will know that he teaches the Apostolic faith. The number one role of the bishop in the Church, aside from the many different purposes he serves in the Church, is to preserve Apostolic Tradition, because this is what they inherited from the Apostles. So when we speak about Apostolic succession, it’s not a mechanical thing, some nice idea or concept. It means that they stand in the succession of the Apostles because they have received the Tradition, and they’re passing it on to the next bishops who come after them, without altering it in any manner.

To be continued.

Presbytera and Dr. Jeannie Constantinou’s podcasts can be found here.