Source: The Times of Israel

October 22, 2015

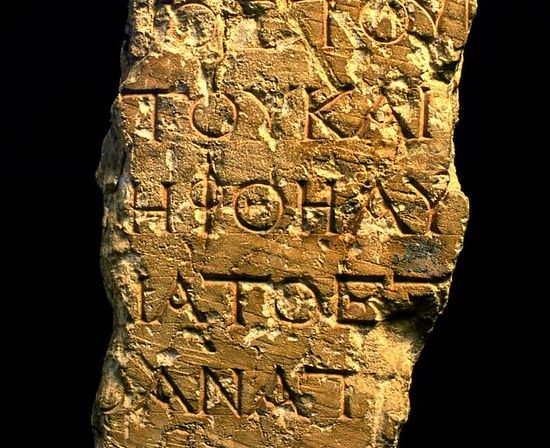

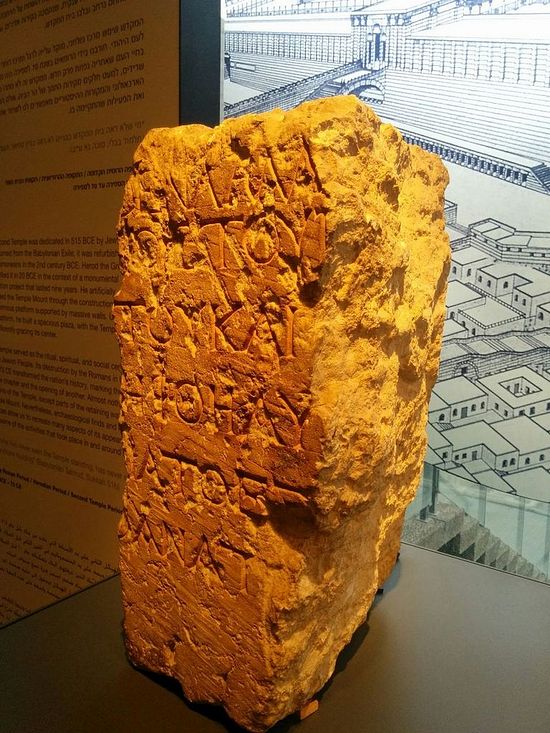

The unassuming slab of limestone doesn’t look like much. It’s crudely fractured and chipped on the sides, pockmarked with age, and is perched not too prominently on a shelf at the Israel Museum. But its smoothly hewn face and crisply etched Greek letters still bearing faint traces of red paint belie monumental significance.

“If we talk about the closest thing to the Temple we have,” said David Mevorach, senior curator of Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine Archaeology, “on the Temple Mount, this was closest.”

Two millennia ago, the block served as one of several Do Not Enter signs in the Second Temple in Jerusalem, delineating a section of the 37-acre complex which was off-limits for the ritually impure — Jews and non-Jews alike. Written in Greek (no Latin versions have survived), they warned: “No foreigner may enter within the balustrade around the sanctuary and the enclosure. Whoever is caught, on himself shall he put blame for the death which will ensue.”

There are actually two extant copies of the warning notices — a partial one here in Jerusalem at the Israel Museum, and a second, complete, one in the Istanbul Archaeology Museum — and they are among a small handful of artifacts conclusively belonging to the shrine built by Herod toward the end of the first century CE. Contemporary accounts mentioned their existence, and 1,800 years after the Temple’s destruction, a French archaeologist found a complete copy that had been incorporated into the wall of a Muslim school in Jerusalem’s Old City.

“It is remarkable that this stone that… comes from the ancient Jewish Temple hasn’t been carried away far from from its original location,” Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau wrote about his 1871 discovery. “Indeed, the place where I found it is only 50 meters away from the Haram al Sharif, the sanctuary of the Jews.”

Shortly after that stone was found it vanished, only to reappear — “mystérieusement,” Clermont-Ganneau wrote — in Istanbul 13 years later. It has remained there ever since. Decades later, the second copy, the partial inscription found in the Israel Museum today, was found during a 1935 excavation being used as spolia in a tomb outside the Lion’s Gate.

The Temple Warning Inscription on display at the Israel Museum (Ilan Ben Zion/Times of Israel staff)

The Temple Warning Inscription on display at the Israel Museum (Ilan Ben Zion/Times of Israel staff)

When it stood, the Temple was the epicenter of religious worship; the place on which it stood remains the holiest site for Jews. But Temple Warning Inscriptions point to universal inclusion — not exclusion — of gentiles on the Temple Mount. (Whether or not Jewish authorities could execute violators, or whether the warning was meant metaphorically, a curse to those who breach the cordon, remains the subject of fierce academic debate.)

The sole literary accounts providing detailed descriptions of the Second Temple’s layout — Josephus’s Jewish War and Jewish Antiquities and Tractate Middah of the Mishna — mention an internal courtyard inside the Temple Mount complex which contained the altar and Holy of Holies. The rabbis of the Mishna, which was compiled and redacted in the century after the Second Temple’s destruction in 70 CE, said the boundary wall (in Hebrew “soreg”) stood roughly three feet high. Josephus gave a detailed description of the warnings placed along it.

“Josephus was a priest who was on the Temple Mount a lot and must have gone past this on a weekly basis,” Jonathan Price, a professor of Classics at Tel Aviv University who specializes in Jewish life in the Roman Empire. “When he’s recalling it, he uses a different Greek word each time, but they all mean foreigner, a non-Jew.”

Together they provide archaeologists with precise archaeological context and “physical evidence of what [Josephus] said,” according to Price.

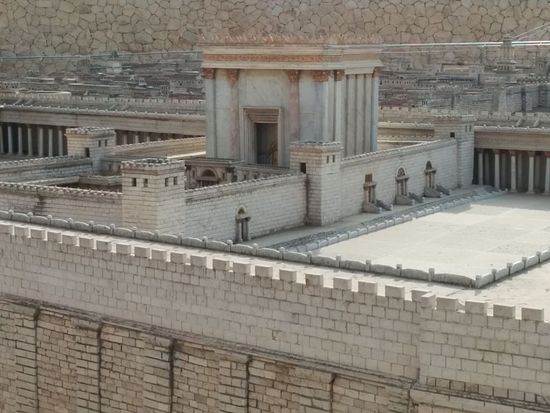

Scholars are uncertain of where exactly this balustrade ran (or where precisely the Temple’s inner shrine stood on the Temple Mount, as The New York Times edified in a recent article), what it looked like, or what exactly it was made of. The Israel Museum’s scale Second Temple model features a low fence running around the central sanctum, but that’s merely the artist’s interpretation, Mevorach said. “The important thing is that it divides the Temple Mount into secular and holy, into Jewish and international.”

The Israel Museum’s Second Temple Model. The “soreg,” a fence partitioning the complex, can be seen to the right of the sanctum, beside the steps. (Ilan Ben Zion/Times of Israel staff)

The Israel Museum’s Second Temple Model. The “soreg,” a fence partitioning the complex, can be seen to the right of the sanctum, beside the steps. (Ilan Ben Zion/Times of Israel staff)

The Herodian Temple was a massive undertaking that it took decades to complete and was funded both from the royal coffers and by international donations. Like any public institution in Israel nowadays, the complex was likely covered with dedicatory inscriptions to patrons who donated funds for Herod’s undertaking. One such inscription, now housed at Haifa’s Hecht Museum, was found in a pile of debris to the south of the Temple Mount. It honors a Paris, son of Akeson of Rhodes for helping fund the paving of the Temple complex in 18 or 17 BCE.

“The level of destruction on the Temple Mount was so extensive that it’s lucky we even have those fragments,” Price said.

Herod decked out the already five-century-old Jewish sanctuary in Classical splendor by engineering an enormous platform atop the hill and ensheathing the refurbished sanctuary in a colossal peristyle courtyard in Greco-Roman fashion. He aimed for that complex, which is today referred to as the Temple Mount and comprises a sixth of the Old City, to be showcased to all.

“The Temple Mount shows us very, very clearly how Herod does his dance between Rome and Judea, between internationalism and Judaism, between his patrons and the people he rules,” said Mevorach, who curated the Israel Museum’s Herod the Great exhibit. “It’s his greatest achievement, he knows that. He wants everyone to come and he wants to host them and show them.”

Contrary to a recent New York Times report which stated that Herod’s Temple was “surrounded by partition walls that were meant to separate gentiles and Jews,” the warning was meant to protect “not the whole Temple Mount, but the inner sanctuary, the inner courtyard,” Price said. The modern notion “that the entire area is somehow holy is contrary to the original purpose and status of this huge plaza of the Temple Mount.”

Gentiles were not only welcome to ascend the Temple Mount, they were also permitted, if not encouraged, to donate animals for sacrifice. Josephus recounts how Marcus Agrippa, Emperor Augustus’s right hand man, visited Jerusalem shortly after the Temple was built and offered up a hecatomb — 100 bulls — as a sacrifice on the altar. Likewise daily sacrifices paid for by the Roman state were offered up for the welfare of the emperors. Philo records in his Embassy to Gaius that on no fewer than three occasions “we did sacrifice, and we offered up entire hecatombs, the blood of which we poured in a libation upon the altar, and the flesh we did not carry to our homes to make a feast and banquet upon it, as it is the custom of some people to do, but we committed the victims entire to the sacred flame as a burnt offering.”

Marcus Agrippa and other gentiles could enter the Temple compound, just not the area where holy rituals took place.

“It was not ethnic or race as much as [ritual] purity,” Price said. “Jews who were not purified or ritually impure could not pass the soreg either.” Unlike gentiles from across the Roman Empire, Jews were expected to know better than to enter the holy sanctum when impure.

Jewish law required any adherent who entered the Temple to be ritually pure, and forbade the entrance of Jews who hadn’t bathed in a mikveh or sprinkled with the purifying ashes of a red heifer since coming in contact with the dead or other defiling agents.

The Temple complex was a series of concentric circles of purity, each area limited to a more select group of people. The innermost, the Holy of Holies, was only accessible to the high priest, and only on the holiest day of the year, the Day of Atonement.

Second Temple-era Judaism had deemed gentiles “intrinsically impure” based on interpretation of a passage from Numbers 18:7, Matan Orian, a PhD student at Tel Aviv University who just completed his dissertation on the Temple Warning Inscription, told The Times of Israel over the phone. Consequently, they were in theory banned altogether from the Temple. Josephus recounts that the Seleucid monarch Antiochus III, father of the villain of the Hannukah story, issued an edict banning “any foreigner to enter the enclosure of the Temple which is forbidden to the Jews, except to those of them who are accustomed to enter after purifying themselves in accordance with the law of the country.”

A contemporary warning sign posted at the entrance to the Temple Mount warning Jews against entrance. (CC BY-SA Bantosh via Wikimedia Commons)

A contemporary warning sign posted at the entrance to the Temple Mount warning Jews against entrance. (CC BY-SA Bantosh via Wikimedia Commons)

“The exclusion of the gentiles, according to the inscription, is a kind of compromise between allowing them into the Temple but still excluding them from the inner temple, which is the properly holy ground,” Orian said.

“Reality necessitates compromise in different aspects of Jewish law,” he said. But “even if they were not viewed as impure, they would still be excluded from the [inner sanctum] of the Temple.”

Despite the Herodian-era status quo, in which gentiles and Jews mingled atop the Temple Mount, most rabbis today maintain the tradition that the entire complex is holy ground and Jewish entry is forbidden. That ban stems from uncertainty over where precisely the Holy of Holies stood.

Echoing the ancient Temple Warning Inscriptions, Israel’s Chief Rabbinate published warning signs, including one on the Mughrabi Bridge leading to the Temple Mount, after Israel assumed control of the site in 1967. “According to the Torah,” these signs stated, “it is forbidden for any person to enter the area of the Temple Mount due to its sacredness.”