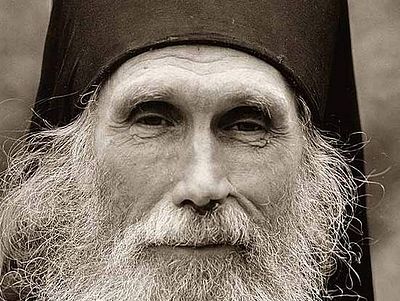

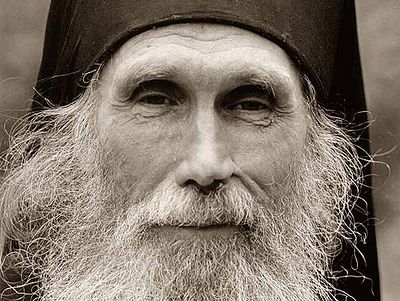

Matushka Evphemia, a novice of Fr. Kirill, called us not long ago, and invited us to bid farewell to the elder with Fr. Vladimir. We had said goodbye to him a few times already over the past ten years, since he became immobile, laid up from a serious illness and no longer getting up. We said goodbye, but nevertheless continued to pray to God that He would extend the life of this precious man at least a little bit—not for him, but for us—for us! Not for him, because for us he was already a man of the Heavenly Kingdom, a saint… Spiritual storms were quieted around him, internal conflicts were resolved, and a blessed inner peace arrived in which everything became transparent and clear. As in the life of one disciple who went up to his elder, sank beside him in silence, and to the question of why he didn’t ask the elder anything, answered, “For me it’s enough just to look at you!”, we had the same sense from being near Fr. Kirill even once.

The elder was lying with his eyes closed, covered with a blanket up to his chin, and only his hands, his kind, soft hands rested on top. We kissed the elder’s warm right hand, venerating it with awe as if a relic, and with such tenderness as to a loved one, as to a father.

Sweet, friendly Matushka [who took care of Fr. Kirill in his illness.—ed.] allowed us to go into his cell; she brought two stools and we sat in silence at the foot of his bed. Here was peaceful and quiet joy, and a feeling of the fullness of life. As always around Fr. Kirill, all worldly troubles, anxiety, and doubts faded, contradictory thoughts fell silent, and the very essence of life was laid bare. In the language of philosophy this is called “phenomenological reduction:” everything is temporal, mutable, and transitory, and relatively diminished to nothing in value, only the soul remaining, standing before God Who created it.

I first went to see Fr. Kirill not long after my Baptism, when I had a spiritual father, a hieromonk at the Lavra, and I began to go see him for confession and conversations. He sent me to the elder for a life confession, and moreover, to resolve some puzzling questions, for which he himself did not dare give answer. He led me to the waiting room of the cell where Fr. Kirill received suffering people, and with trepidation I settled into a spot on the bench, waiting my turn and listening to the words of the Psalter which was read to pilgrims.

The fact of the matter is that my entrance into the enclosure of the Church after my Baptism was truly the turning point of my life: I immediately went to a monastic skete with hours-long services, with severe fasting, with monks, with theological students, with locally-revered clairvoyants, with those wearing chains and holy fools, with my spiritual father-ascetic, with frequent confession and a prayer rule. I really wanted to truly kill “the old man” within myself and to resurrect to new life. I wanted to offer a sacrifice. But I had nothing: “Make haste to open unto me Thy fatherly embrace, for as the Prodigal I have wasted my life. In the unfailing wealth of Thy mercy, O Saviour, reject not my heart in its poverty.”1 The only thing that I felt my own, received as a precious gift, was the writing of poetry, but I decided to abandon it in the name of a new life: I offered it as a sacrifice, as formerly virgins, adorned in monastic clothes, brought their purity and beauty to Christ, and boys their riches and young strength. However, I understood (having already read in spiritual literature) that it was impossible to take any step without a blessing, lest it be an act of self-will and result in “humiliation worse than pride.” My spiritual father, whom my desire and gusto surprised, if not frightened, sent me to Fr. Kill for this blessing (or non-blessing).

Finally my turn came and I went in to see the elder. And here was the look of love, the ground of love, the energy of love, the joy of love, the agony of love… I began to cry… And that’s how it always was then when I would see Fr. Kirill—tears would involuntarily appear, flowing inexplicably—from repentance, from jubilation, from tenderness, from the feeling of the fullness of life, and from the feeling that the “the Kingdom of Heaven is at hand.” Whether I caught sight of Fr. Kirill in the altar at the Church of the Transfiguration of the Lord in Peredelkino, or went to him for Confession, or was standing by his sickbed, this emotional and spiritual upheaval and catharsis always happened to me.

The first time I confessed to him, but then he suddenly began to ask me questions about something I didn’t consider a sin, and I wondered how he saw it in me. But about my decision “to sacrifice,” he suddenly somehow roused up, even threw up, if not waving, his hands, and, smiling, shook his head no: “No, no. It’s not necessary to renounce this. Why? You will still write!” And he blessed me.

Looking ahead, I must say that he then always asked me about what I was writing, and himself insisted that I must write “for the glory of God, in defense of the Church.” He blessed me…

Then my husband and I started going to the Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra quite often with our children. It seems to me now that this was, despite the bleak-for-the-Church Brezhnev era, the Lavra’s heyday. There were elders and old monks who had passed through camps and trials, there were young, strong spiritual fathers who later became hierarchs and abbots of monasteries—the current Metropolitan Onuphry of Kiev and Metropolitan Daniel of Arkhangelsk, Archbishop Dimitry of Vitebsk, Archimandrite Alexei (the abbot of Danilov Monastery), and Archimandrite Benedict (the abbot of Optina Pustyn) and many, many other worthy pastors. We have continued very friendly relations with some of them to this day.

I still pray from the prayer book that the still young Archimandrite Benedict gave me in those years. The prayer book is worn out and scuffed up from frequent use, but I cherish it like a spiritual relic…

We confessed to our spiritual father, but in exceptional cases we consulted with Fr. Kirill. He had an amazing quality—he never imposed anything on a person, he gave no instructions, but gently led his guest in conversation to suddenly himself pronounce a way out of the situation, for which the elder would bless him. Sometimes we brought suffering people to him, and he helped them.

Once we brought a young woman to him whose baby was born with cerebral palsy. Fr. Kirill heard her out and … gave her money. A lot. She left him a little perplexed—she expected that through the prayers of the elder her child would have gotten up and walked, or that the elder would have said something miraculous, speaking a prophecy… She was confused. But literally the next day the doctor said that her child needed an extended course of massage, and it turned out that the cost of the sessions was exactly the amount that Fr. Kirill had given her.

Another time we brought him another young woman with a sick five-year-old son. His ailment was that he did not speak. He would look with his big eyes and say nothing. Fr. Kirill received them, prayed, and soon the boy not only began to speak, but displayed certain special abilities. Now he is a very successful businessman with his own children, and it’s unlikely he even remembers his childhood malady.

Our relationship with Fr. Kirill connected us with Archbishop Dimitry (then a hierodeacon). He was then working as a secretary in the patriarchate and lived in Moscow, longing for the Lavra, for his spiritual father Archimandrite Kirill, and for the monastic brotherhood. And Fr. Kirill gave him the obedience to visit us in his free time and catechize us.

Fr. Dimitry was then studying at the Theological Academy, and he was willing to enlighten us, systematically using his notes, while at the same time preparing for exams. He would come, open his notebooks, and literally read to us his course lectures on dogmatics, ethics, comparative theology, Church history, homiletics, and so on. We also asked him numerous questions, brought on by our religious ignorance, which he either answered himself (almost always), or, in special cases, he wrote them down and then asked Fr. Kirill. He went to him weekly at the Lavra for Confession. Returning, he read the answers to us, and they struck us by their wisdom and simplicity. For some reason I remembered one such answer, seemingly having little relation to my life, but very valuable by its contents. The question was: “Should I leave a tip?” Fr. Kirill answered that if you feel bad for the person, then give, but if you just want to show off, then don’t.

I remember his answer to one question, it seems, about the fate of the world. Fr. Kirill said some wonderful words about how our Earth has gotten older, as does every natural body. It’s old, and has little strength left, and we must pity it… What an amazing, gentle, and compassionate attitude towards our planet, to all living things that are born and grow from it, to nature itself, imbued with heavenly light.

Fr. Dimitry, who had already accumulated a whole notebook of such questions and answers, once told us that such a spiritually useful book could be published later, and called on us to fill out the number of confusing issues that needed the elder’s clarification. We then formulated many questions for Fr. Kirill, touching upon the most varied spheres of life, from the mystical to the social. However, a very short time later, Fr. Dimitry appeared and told us, not without regret, that the elder had forbidden him to record and gather his answers, and especially to publish them. Quite the contrary, he advised us to burn these notes, and the humble Fr. Dimitry obeyed, and burned them.

However, many years later he regretted it and even insinuated that it’s not worth it to comply with some blessings with such haste.

Another person that connected us with Fr. Kirill was Monk Leonid—the wretched, as he called himself. He had a strange disease: from his waist up he looked like an old woman, but the lower half of his body was male. Because of this he was pierced with many temptations; he came through great sorrows. Once, he and Fr. Kirill were working at the renowned Glinsk Hermitage, which at that time (in the Khrushchev era) they had dispersed, and he wandered, homeless and feckless. Then the Lord gave him shelter and a novice—the elderly handmaiden of God Nun Pelagia. But he greatly revered Fr. Kirill from their time at the hermitage, and until the end of his life he considered him his spiritual father.

We met him at the funeral of Elder Seraphim Tyapochkin and since then we have seen him often. One half of his body (the right) was paralyzed, and he asked me to get a blessing from Fr. Kirill to record his confession, as he was quite limited in movement and often could not make it to the Lavra. Fr. Kirill blessed me and I began to regularly visit Fr. Leonid (he lived in Moscow, a few stops from Elektrozavodskaya metro station) and record what he dictated to me. Of course, I cannot disclose what this poor monk confessed, but I can testify that he was a man of holy life. Sometimes I would fill up two notebooks, all the while remembering recording the metaphors of the confessions of the righteous: In a beam of light every speck of dust is visible, but in the darkness even a pile of dirt can’t be made out; and then I would take them to Fr. Kirill. Fr. Kirill would read the prayer of absolution and tear them up, without reading them. But Fr. Leonid asked me to tell the elder about his obsessive thought, whispering, as if he was tearing up the notebooks, not having read them. It seemed to me I was living amongst saints, who see one another with spiritual vision.

Fr. Leonid was very interested in spiritual books, or “lil' books” as he called them, playing the fool.2 “Do you have any spiritual lil' books on the New Martyrs?” he would ask everyone that visited him with requests for guidance and prayer. And somehow a book published abroad, Signs of the Last Times by Fr. Seraphim Rose, made its way to him. It really spoke to his heart and he decided to distribute it (taking a blessing from Fr. Kirill). Fr. Leonid ordered a reprinting of twenty copies of the book and handed them out to his unenlightened acquaintances. At one point he wanted to pray for Hieromonk Seraphim, needing only to clarify whether to commemorate him for his health or his repose. No one around knew if he was alive or dead. So Fr. Leonid decided to go to the Lavra to Fr. Kirill to ask about it.

My husband Fr. Vladimir took him right to the evening service, and Fr. Leonid went into the altar, where Fr. Kirill was praying. He went up to him with this question, and Fr. Kirill (according to Fr. Leonid’s story) lifted his eyes to Heaven and saw something there with inner vision, and exclaimed: “Give rest, O Lord, to Thy servant the hieromonk Seraphim.”

Amazingly, it turned out that Hieromonk Seraphim had died just a day or two before.

I turned to Fr. Kirill in exceptional cases. My heart was sick for my mama—she was very sick, practically dying, and I worried that she would die unbaptized. But Fr. Kirill firmly stated that she would be baptized, live yet for many years, and become a believer. And that’s what happened, despite the fact that it seemed impossible at that time. They released her from the hospital because they didn’t want “to spoil the statistics for the dead.”

Then my husband, Fr. Vladimir, got sick. They found a malignant tumor and he needed to have an operation. It was very scary. We asked Fr. Kirill’s cell attendant—Sister Natalia (now Nun Evfimia)—to tell the elder about it. And suddenly she called and said that she was coming with Fr. Kirill to our home to visit Fr. Vladimir before the operation!

Fr. Kirill was already living not at the Lavra but in Peredelkino. He was sick but still able to walk, and so he and Sister Natalia came to see us. It was such a great comfort, such joy! And my mama, for whom he had prayed for many years until then, was with us, safe and sound.

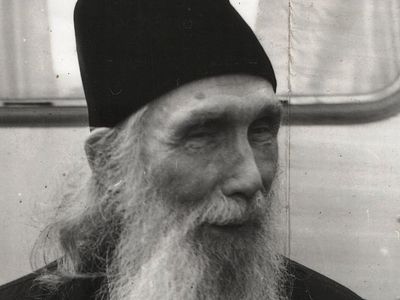

I have a photo of Fr. Kirill sitting next to Fr. Vladimir on the couch, smiles on their faces, snacks in front of them, and across from them (not in the photograph)—my mama, me and Sister Natalia and Michael, a graduate of the Moscow Theological Academy. Fr. Kirill asked him to sing some Cossack songs that he really loved. And we sat and talked and listened to the songs, and Fr. Kirill was with us, and it’s as if I can this picture in real life. It’s perhaps one of the great treasures of my life.

And within a few days, Fr. Vladimir had a very serious operation that lasted six hours, and he woke up in the intensive care unit, then began to come to himself and recover, and glorify God.

I would turn to the elder for less dramatic and significant reasons. Sometimes they were creative problems: Should I undertake the translation from French of the theology book, St. Maximus the Confessor: Mediator Between East and West by a Catholic who became Orthodox?

Is it in spiritual bad taste if the main characters—monks—in my novel are not depicted hagiographically, but are distinguished by a lively mind and character, and if sometimes, in following the logic of the novel, I described their temptations and spiritual infirmities?

And another question: since Church and even monastery publishing houses have started publishing me, should I change my name Olesya (given by my parents from a literary work of Kuprin) to my baptismal name of Olga, and my parent’s surname Nikolaeva to that of my husband, Vigilyanskaya? And every time Fr. Kirill listened to my questions with great attentiveness and with personal involvement would vividly respond that I should translate the French book. “It will be useful for you!”; finish the novel, writing “whatever God lays on your heart;” don’t change your name he said, even waving his hand, as if dismissing this care as a superfluous fuss. “Remain as you are!”

And every time after visiting Fr. Kirill there came enlightenment, liberation, and joy!

I had a really dead end problem connected with some everyday problems: We (my husband, three children, and I) lived in very close quarters, in one apartment with my parents and my brother’s large family. Some internecine conflicts arose, it was practically impossible to work at home, there was no room in the shared kitchen in the evening, and it escalated into an existential drama. Fr. Kirill said to me, “The Lord loves you—He gives you His tribulation! He had nowhere to lay his head! Rejoice!” And I truly rejoiced.

Prophecies were heard from the mouth of Fr. Kirill. Often, when people asked him about how to properly arrange their lives, he would bless them to buy a wooden house with a stove, a well, and a plot of land, as if pushing the thought that there is coming such a time when only there would we be able to warm and feed ourselves.

Once, when my husband was not only not a priest yet, but hadn’t even dreamt or thought about it, he foretold his future path. It went like this: My husband arrived at the Lavra and confessed to Fr. Kirill in the altar, kneeling near the altar itself. Getting up from his knees, he stumbled a bit and touched the altar. Fr. Kirill contritely bowed his head and said: “What are you doing? You’re not a priest yet!” These words were etched in his memory and proved to be an omen.

Those who asked for Fr. Kirill’s blessing and received it but acted contrarily were to be pitied… This happened sometimes. One of my good friends asked him whether he should have an operation, or would it pass by itself. Fr. Kirill became agitated and said sharply: “Do it.” But then he got afraid: ‘Well, the elder isn’t a doctor, he doesn’t understand medicine, and besides, it’s winter—it’s better to wait for the warm season—I’ll have time then,” and so son. But, he never found time.

Fr. Kirill seriously begged (!) one beautiful girl not to marry the guy she wanted to… She cried. The elder comforted her, but was firm: “No, no!” She did it her way anyways, and her young husband turned out be an old drug addict. It all turned into disaster and suffering.

And there were other instances. One mother’s son was taken into the army and sent to Afghanistan. She prayed for him day and night, the tears ran, and she went to Fr. Kirill at the Lavra, beseeching his holy prayers. He said he would be praying for her son to return alive and in one piece, but afterwards he should return to him to thank the Lord. Her son really did return home, which was a miracle in and of itself—all his comrades-in-arms perished, he alone escaping from the fiery furnace. His mother listened and agreed that the Lord had saved him. He planned to go see Fr. Kirill at the Lavra, but somehow his life began to spin and swirl: worries, hassles, work. And he never could choose a time to do it.

He worked as a taxi driver. Then one time my mom asked me to move one ancient, wonderworking icon from our house to the dacha. I didn’t have a car then, so I wrapped the icon in a towel and went out on the street and began to hail a cab. And here that very taxi driver stopped (he later said, “I don’t know why I picked you up. My work day was already over and I was going to the park.”), and agreed to drive through Moscow in the traffic to Peredelkino. While we were driving, seeing the icon under the towel, he told me a story, saying his mother prays and knows elders. To make a long story short, as we were approaching the dacha, I found out that the elder who wanted him to come see him after Afghanistan was Fr. Kirill. I knew that at precisely that time Fr. Kirill was receiving believers in Peredelkino, in the baptistery of the Church of the Transfiguration of the Lord.

“Well, now finally you’re getting to see him!” I said to him. “It looks like that’s why you drove me through the whole city to my dacha, even though by sound reasoning that wasn’t why.”

And after dropping me off, this taxi driver rushed off down the hill towards the church.

But there were other more mysterious things connected with Fr. Kirill. Difficult and tempting times were coming, clouds were brewing on the spiritual horizon, and Fr. Kirill helped to disperse them. There were some spiritual attacks and intrigues… He prayed, and everything dissipated.

Once I went to see him at the Lavra in a period of complete physical exhaustion—I was overworked, had fasted too hard, and fell into fierce insomnia; there was a host of questions, problems, and dead end situations… Fr. Kirill heard me out, sighed sympathetically, and said, “You need some rest!” I left him, painfully weighing where to find whoever could give me this rest in my circumstances. I went to the Trinity Church, and the priest had just finished an Akathist and was reading the Gospel.

I stopped and heard, Come unto me, all ye that labour and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn of me; for I am meek and lowly in heart: and ye shall find rest unto your souls (Mt. 11:28-29). And he so drew out that word rest, as if breathing it into me. Meek and lowly in heart.

And here, when I was standing in Fr. Kirill’s cell yesterday, saying goodbye to him, and when I came to see him so many times in my life, I discovered precisely this rest, this peace, and this grace, testifying that Christ’s yoke truly is good, and His burden easy. This revelation was always present around the elder, as the fruit of a humble and meek heart that exudes love and in which he embraced all.

And his soft hand, the hand of a good man, comforting and blessing, now lying motionlessly atop the blanket, now seemingly only partly belongs to this world. And dear Fr. Kirill himself remained on his sickbed in his body, but in spirit he was somewhere out there where the righteous shine like lanterns. During his life he illuminated us with this light, driving away the delusion and darkness.

Grant rest eternal in blessed repose, O Lord, to the soul of thy newly-departed servant Archimandrite Kirill, and make his memory to be eternal!