It was the year after the war ended, 1946. Lately demobilized George Stepanov was ordained a priest by Metropolitan George (Chukov). The newly ordained priest was sent to serve in a small church dedicated to the Tikhvin Icon of the Mother of God in the village of Romanshchina, Luzhkov region, Leningrad province.

Romanshchina was a historical place. From 1799 the village was owned by Marquis Ivan Ivanovich de Traverse, who was a minister of the navy during the reign of Alexander I. Enjoying the Emperor’s good graces, Admiral de Traverse had received him a number of times in Romanshchina. A bronze plaque with a commemorative inscription built into the altar of the Tikhvin Church bore witness to one of these visits.

In 1938 the church was closed. Then the war began, and the Germans occupied Romanshchina. The fascists desecrated God’s house, first using it as an animal slaughterhouse, and then spilling human blood in it: In that church they executed partisans and captives—the elderly, women, and even children. Before their retreat the occupying forces herded the rest of the villagers into the guardhouse next to the church, poured gasoline over it, and set it on fire.

When Fr. George arrived at the parish he was met with a horrifying scene. During the war he had seen all sorts of things, but he shuddered at the recollection of that sight the rest of his life. “When we entered the church we saw the remains of the executed, who lay on the church floor… All of us who came there gathered the charred bones of those who had perished in the fire and buried them in one large grave. There was so much sorrow, so many tears! People fainted as they attempted to find their close ones but in vain—the flames had mercilessly devoured them all.”

They buried the dead, cleaned the church, and re-consecrated it; then batiushka began serving there. Nevertheless, the ruined church needed immediate repairs. But where could the money be found for this? The diocese could not help, and it goes without saying that they could expect no help from the secular authorities. All around was post-war ruination, poverty, and hunger. In those times no one thanked the priest with donations for needs performed (there simply wasn’t any money). Batiushka remembered how one day after a funeral service someone handed him a piece of gray paper with two small lumps of shaved sugar. That was a real prize in those hungry days…

There was nothing left to do but hope in God’s help and pray. A total orphan since childhood, having gone through interrogations in the Svir concentration camp, and been many times a hair’s breadth away from death in the war, Fr. George knew from his own experience that those who put their hope in God will not be put to shame. He also hoped in the intercessions of St. Nicholas, whose icon—with which his deeply religious grandmother had blessed him—he never parted with anytime or anywhere.

One day, Fr. George was serving the Liturgy. There were very few people in the church. His altar attendant was an elderly nun who lived next to the church—Mother Evgenia. “After taking Communion,” batiushka remembered, “I came out to hear confessions. There were three who came for confession that day: two women and an unfamiliar elderly man with a noble appearance. I didn’t pay particular attention to him, and I don’t remember what he said to me in confession, either. Having covered him with the epitrachelion for absolution, I went into the altar. I opened the royal doors and pronounced, ‘In fear of God and faith and love draw nigh!’ Two women approached, but the old man was gone. ‘Where is he?’ I thought, ‘Did he leave?’ Well, anything could happen. I communed the two women, finished the service, and went to remove my vestments. Suddenly the ordinarily decorious Mother Evgenia literally flew into the altar, her apostolnik (head covering) ajar from excitement, exclaiming, ‘Batiushechka, Batiushechka, look how much money they’ve gone and left you in the plate!’ ‘What are you saying, Matushka! Calm down. What money could there be?’ But she handed me a large bundle wrapped in paper. I opened it, and there was an enormous sum of money! Cleaning the church after the service she had discovered this bundle on the plate near the confessional. No one but the old man who had come to confession last and then left could have deposited it… Then I understood. ‘No, Mother Evgenia, this wasn’t brought for me!’”

Soon Fr. George and the churchwarden went to the city and bought everything needed for repairs: boards, nails, metal, whitewash, and so forth. It is probably needless to say that the sum matched the costs exactly. The church was repaired.

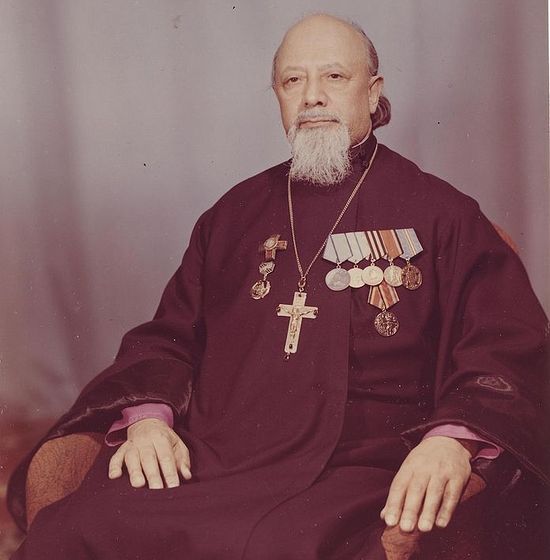

The renewed church was open until 1962, when the authorities closed it. After being moved from parish to parish in Leningrad and Tula provinces, Fr. George was appointed in 1955 to the church of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker in Kochaki, near Yasnaya Polyana, where he served as head priest for thirty years. Until his final days, batiushka continued to be amazed at God’s mercy shown in Romanshchina, and was firmly convinced that the old man who brought money “for confession” was none other than St. Nicholas.